Outbreak Investigation Report on Avian Influenza in British Columbia, 2014

Table of Contents

- List of acronyms

- Report Objective

- Summary

- 1. The Fraser Valley of British Columbia - Outbreak Context

- 2. National Avian Influenza Surveillance

- 3. Overview of Outbreak

-

4. Disease Control Actions

- 4.1. Response Infrastructure

- 4.2. Disease Control Zoning

- 4.3. Epidemiological Tracing

- 4.4. Laboratory Investigation

- 4.5. Movement Restrictions and Permitting

- 4.6. Surveillance

- 4.7. Depopulation and Disposal Activities

- 4.8. Cleaning and Disinfection of Facilities and Equipment

- 4.9. Release of Quarantine on Infected Premises

- 4.10. Release of Movement Restrictions on Non-Infected farms

- 4.11. Three-Month Enhanced Surveillance

- 4.12. HPAI Freedom declaration

- 5. Summary of Findings and Working Hypotheses on Source and Transmission of NAI

- 6. Communications

- 7. The Role of Poultry Organizations

List of acronyms

- AEOC

- Area Emergency Operations Centre

- AHC

- Animal Health Centre (BCMAGRI)

- AHFP

- Animal Health Functional Plan

- BCCDC

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control

- BCMAGRI

- British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture

- BCPA

- British Columbia Poultry Association

- BHT

- Biological Heat Treatment

- C&D

- Cleaning and disinfection

- CAHLN

- Canadian Animal Health Laboratory Network

- CanNAISS

- Canadian Notifiable Avian Influenza Surveillance System

- CFIA

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- CVO

- Chief Veterinary Officer

- CWS

- Canadian Wildlife Service

- EOC

- Emergency Operations Centre

- FADES

- Foreign Animal Disease Emergency Support (plan)

- FHA

- Fraser Health Authority

- GIS

- Geographic Information System

- HPAI

- Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza

- HSP

- Hazard Specific Plan

- ICP

- Incident Command Post

- ICS

- Incident Command System

- IP

- Infected Premises

- IZ

- Infected Zone

- JEOC

- Joint Emergency Operations Centre

- NAI

- Notifiable Avian Influenza

- NCFAD

- National Centre for Foreign Animal Diseases

- NEOC

- National Emergency Operations Centre

- OHS

- Occupational Health and Safety

- WOAH

- World Organization for Animal Health

- PCZ

- Primary Control Zone

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PIQ

- Premises Investigation Questionnaire

- PPE

- Personal Protective Equipment

- RZ

- Restricted Zone

- TAHC

- Terrestrial Animal Health Code

- USDA

- United States Department of Agriculture

Report Objective

This investigative report was prepared in order to apprise Canadian trading partners that appropriate disease control measures have been implemented to manage the occurrence of a reportable disease: HPAI. In addition, this report provides information that Canada has stamped out HPAI and has met all international trading obligations in accordance with current World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH; founded as Office International des Épizooties (OIE)) guidelines.

Summary

- HPAI was identified in a broiler breeder chicken farm and a meat turkey farm in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia, Canada on December 1st, 2014. Subsequently, nine other commercial farms were infected with the same virus: six broiler breeders, two meat turkey, and one table egg layer. In addition, two non-commercial poultry flocks were also infected. All birds on infected farms were humanely destroyed and composted on-site.

- The virus at the first 12 premises was identified as H5N2, a reassortant virus with the H5 from the highly pathogenic Eurasian H5N8 virus and the N2 from a North American virus. It was the first time a Eurasian HPAI H5 virus caused an outbreak of avian influenza in domestic poultry in North America. The 13th premises was a non-commercial flock infected with an H5N1 strain.

- Movement restrictions were placed on 404 farms: 254 of these were located in the restricted zones and 150 were located in the infected zones, including the 11 infected commercial farms.

- The CFIA undertook a complete outbreak investigation, including an epidemiological analysis. It was determined that:

- For three commercial farms, the source of the virus was contact with infected farm birds and/or service personnel.

- For five commercial farms and the non-commercial farms, the source of the virus was contact with wild birds.

- For three commercial farms, the source of the virus is suspected to be localized/environmental spread.

- Surveillance was completed on over 400 commercial farms during the outbreak period with over 8,300 samples collected testing negative for HPAI virus.

- During the post-outbreak period, three months subsequent to the completion of cleaning and disinfection on all infected farms (March 3rd to June 3rd, 2015), post outbreak surveillance was undertaken. This period of enhanced surveillance for AI in BC met requirements to regain disease-free status.

- On June 3rd, 2015, in accordance with Article 10.4.3.1 of the WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health Code, the province of British Columbia regained its disease-free status with regard to Avian Influenza. The WOAH was notified on June 8th, 2015.

1. The Fraser Valley of British Columbia - Outbreak Context

1.1. Geography and Climate

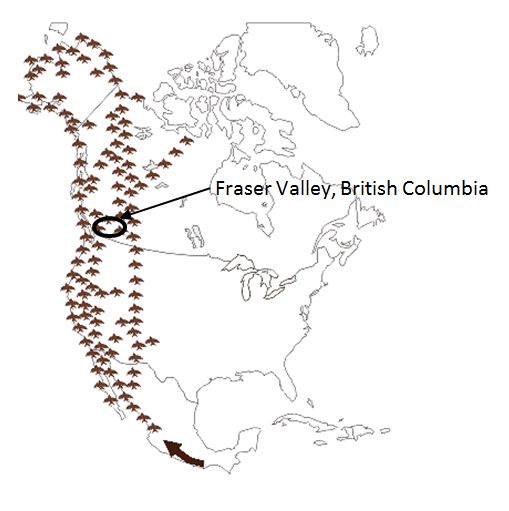

The Fraser Valley is a fertile floodplain that follows the Fraser River through the Pacific Coast Mountain Ranges from Abbotsford and Mission eastward to Hope. It is one of the most diverse and intensively farmed areas in Canada. The climate of the Fraser Valley attracts many species of wild resident and migratory waterfowl and shorebirds (eBird Canada). The Fraser Valley lies within the Pacific Flyway (Figure 1), which extends from the western Arctic through the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Coast regions of Canada, the United States and Mexico, south to where it blends with other flyways in Central and South America.

The Fraser Valley normally experiences heavy seasonal rainfall in November. In 2014, Abbotsford received 232.5 mm total precipitation with a mean monthly temperature of 6°C. Most (over 67%) of the precipitation fell as rain over eight days from the 20th to the 28th, During which period there was an average daily rainfall of over 17 mm and a mean daily temperature of 7°C. As a result, there were reports of increased standing water on farms. This rainy period was immediately followed by colder temperatures of -4.6 and -4.7°C on November 29th and 30th and no measurable precipitation until December 3rd. Then there were six days that saw 90 mm of rain and a mean daily temperature of 9.5°C. Overall, the month of December 2014 experienced higher than normal average temperatures (5.1°C) and precipitation (214.2 mm).

Figure 1: The Pacific Flyway (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department)

Description for photo - The Pacific Flyway

This map shows the south to north path of the Pacific Flyway through North America. The Fraser Valley of British Columbia is located in the flyway. The bird migration route extends from Alaska to Patagonia and follows the west coast of North America with incursions into Western States of the United States, covering all of British Columbia and extending to the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada in northwestern Canada.

1.2. Structure of the Poultry Industry

The commercial poultry industry in BC is highly integrated. Each sector is represented by a separate organization, and there are marketing boards for broiler chickens, commercial turkeys, table eggs, and hatching eggs. These groups work together to address biosecurity issues, establish premises identification programs, and motivate producers to cooperate with disease surveillance and control programs. Outside the supply-managed sectors, other smaller sectors include layer breeders, ducks, geese, squab, pheasant, quail, and specialty chickens. In addition to the commodity specific groups, the BC Poultry Association (BCPA) is a joint producer association comprised of representatives from each sector.

The non-commercial poultry sector in the Fraser Valley is diverse and individual production systems are unique. There is no mandatory registry for the non-commercial poultry sector.

The poultry sector is economically important to BC, with farm production sales of $632 million in 2013. There are approximately 850 regulated commercial poultry producers in British Columbia. Eighty percent of production occurs in the Fraser Valley.

1.3. Biosecurity

The BCPA has taken an active role in the development and implementation of a biosecurity program. In December 2008, the BC Biosecurity Program became mandatory for all commercial poultry operations in the province. All regulated farms are audited for compliance.

A Self-Assessment Tool and Biosecurity Guide were created by industry and government partners for non-commercial poultry producers to increase biosecurity awareness; facilitate identification of biosecurity risks and encourage implementation of enhanced biosecurity protocols. In response to the 2014 outbreak, the BC Ministry of Agriculture (BCMAGRI) organized town hall meetings and conference calls for small flock and specialty bird producers to raise awareness about biosecurity.

1.4. Premises Identification

All regulated commercial poultry operations have been geo-referenced and a database is available to assist the CFIA to locate poultry farms during an outbreak response. All commercial poultry farms in BC have a unique alpha-numeric Premises ID, assigned and managed by the BCMAGRI. Premises IDs are posted on bright orange signs at the entrance of each farm and designated sub-premises numbers are attached to each barn.

2. National Avian Influenza Surveillance

2.1. Commercial Poultry

The Canadian Notifiable Avian Influenza Surveillance System (CanNAISS) is a joint initiative of government and industry that supports Canada's claim of freedom from NAI by providing ongoing surveillance of the commercial poultry population. The System is intended to prevent, detect and/or demonstrate the freedom from NAI in Canada's domestic poultry flocks. Designed to meet WOAH guidelines, CanNAISS pertains specifically to high-pathogenic avian influenza and low-pathogenic H5 and H7 subtypes of NAI. During an outbreak of NAI, CanNAISS provides surveillance on premises and areas not part of the outbreak, complementing the CFIA's NAI Hazard Specific Plan (HSP) and supporting Canada's reporting to international organizations such as the WOAH.

The CanNAISS includes:

- Detection of HPAI in domestic poultry through passive surveillance;

- Verification of the effectiveness of passive surveillance through active surveillance;

- Detection of LPAI circulating in domestic poultry through active surveillance; and

- Detection of NAI in post-outbreak surveillance.

2.2. Wild Birds

In 2005, Canada initiated an inter-agency annual survey for influenza A viruses in wild birds. These surveys (2005-2014) are used to assess the risk of exposure of AI virus from migrating wild birds to poultry. To date, no highly pathogenic H5 viruses have been detected.

The BCMAGRI Animal Health Centre (BCMAGRI-AHC) has tested dead wild birds from BC annually since 2006. The number of yearly submissions has ranged from 200-600 birds. In 2014, more than 300 dead wild birds were tested in BC, with no positive results for H5 or H7 avian influenza reported. In both 2006 and 2008, one dead bird out of the total annual collection (n=639 and n=386, respectively) tested positive for an H7 and H5 virus of low pathogenicity, respectively.

3. Overview of Outbreak

3.1. Initial Detection

On December 1st, 2014, the Chief Veterinary Officer for Canada (CVO) received notification from the British Columbia (BC) CVO of an NAI suspect on two farms: a broiler breeder farm in Chilliwack (IP1) and a commercial turkey farm in Abbotsford (IP2).

Preliminary testing of samples from the two farms (IP1 and IP2) at the BCMAGRI-AHC in Abbotsford confirmed the presence of H5 avian influenza. The CFIA immediately quarantined the two infected farms.

On December 2, 2014 the CFIA established an incident command post (ICP) in the Animal Health District Office in Abbotsford, BC.

Under official quarantine, movement of poultry, poultry products and by-products on and of farms was not allowed. Farms located within 10 km of the IPs were identified through the provincial Premises ID program.

On December 2nd and 3rd, CFIA staff collected additional samples from IP1 and IP2 for diagnosis as per the NAI HSP. Blood, swab and tissue samples from birds on IP1 and IP2 were sent to the NCFAD for confirmatory testing on December 3rd, 2014.

On December 4th, based on the results from partial sequencing of the virus, the NCFAD confirmed the strain associated with the outbreak as being a highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N2.

The CFIA activated an Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) in collaboration with the province of BC as a Joint Emergency Operations Centre (JEOC), which was co-located with an Incident Command Post (ICP) in the Abbotsford District Office. A national EOC (NEOC) was activated in Ottawa, ON.

3.2. Findings on Infected Premises 1

This multi-staged chicken broiler breeder operation located near Chilliwack, BC is composed of five barns housing the following number of birds:

- Barn 1 (B1) housed 7,000 hens and 1,000 roosters aged 25 weeks;

- Barn 2 (B2) housed 4,500 hens and 300 roosters aged 51 weeks; and

- Barns 3-5 were empty.

On Friday November 28th, 2014, the owner noticed 16 dead birds in B1. These roosters, a.k.a. 'spiking' roosters, were being raised to be sold to other producers. On Saturday November 29th, the owner noted 30 dead birds in B1 and became concerned about the cause.

On the morning of Sunday, November 30th, the farmer noticed 88 dead birds and contacted his veterinarian. The farmer submitted ten carcasses for post mortem and incinerated all remaining carcasses on site. The post-mortem findings were inconclusive, with only non-specific signs of disease present on gross pathology: facial oedema, conjunctivitis, with tracheal and pulmonary congestion.

On December 1st, the producer noted approximately 450 dead birds during his morning walk-through. These birds were removed from B1 to an empty barn where they were secured using a heavy-duty tarp. The private veterinarian collected tracheal and cloacal swabs from live birds in B1 for submission to BCMAGRI-AHC. The tissue samples from the post mortem of the day before were also submitted to the BCMAGRI-AHC.

BCMAGRI-AHC reported results the same day (December 1st) as H5 positive on PCR, with gross lesions compatible with HPAI. The CFIA contacted the owner to inform him of the presumptive positive result. The farm was placed under official quarantine later that evening.

Field epidemiological investigations, were conducted on IP1. It was determined that the HPAI virus isolated from IP1 was likely introduced as a result of an indirect exposure to a wild bird reservoir and to local environmental contamination. Ducks had been seen around the farm. Weather conditions may have increased the number of wild waterfowl and rodents seeking shelter, possibly increasing the likelihood of these animals serving as vectors of the AI virus. In addition, wild waterfowl were observed in the draining ditch on the farm. The owners were away from November 4th to 20th, leading to an increased potential for possible biosecurity lapses by employees.

The movement tracing investigation identified two high-risk contact farms in the city of Abbotsford. These two farms (IP3 and IP4) had received spiking roosters on November 28th and 27th from IP1 and developed clinical signs on December 3rd and 2nd. They were both quarantined and sampled on December 3rd.

3.3. Findings on Infected Premises 2

This commercial turkey operation located near Abbotsford, BC is composed of three barns that housed the following number of birds by age:

- B1: 11,000 males and 3,000 females, aged 2 weeks

- B2: 3,000 turkey hens, aged 12 weeks

- B3: 11,000 turkey toms, aged 12 weeks

The first clinical sign noted was a decrease in water consumption in B3 on November 26th, followed by increased mortality over the next few days, and massive mortality on December 1st:

- November 27th: 18 toms dead

- December 1st: 60 - 70% toms dead

- December 3rd: almost all birds were dead in B3

On November 28th, the farmer called his private veterinarian. The veterinarian went into B3 only. He noted that the birds were bright, alert, and responsive. He performed on-site post-mortems of five dead birds, plus one sick bird. On necropsy, the trachea and lungs looked normal; there was splenomegaly, and possible pericarditis. There was bloody fluid present in the abdominal cavity. He suspected a bacterial infection, and provided the owner with antibiotics.

On December 1st, due to the dramatic increase in mortalities, the veterinarian came back to the farm and took samples; six carcasses and three sets of swabs were submitted to BCMAGRI-AHC. The presumptive positive results NAI subtype H5 were obtained and the farm was placed under official quarantine on the same day. On December 4th, birds in B2 began to demonstrate an increase in mortality.

Based on the detailed epidemiological investigation that followed, it was determined that this IP had no direct links to IP1 (different bird types, did not share personnel or equipment, used different hatcheries, feed companies and veterinarians).

Similar to IP1, exposure to the HPAI virus through indirect exposure to contaminated wild birds is likely how the virus was introduced into IP2. It was also determined that the virus was unlikely to have spread from this IP, as there was limited traffic onto and off the farm.

3.4. Laboratory Findings

Sequencing of the H5N2 virus obtained from samples of poultry on infected farms and analysis of the results indicated that it was a reassortant virus. The genome of all Influenza A viruses contains eight RNA gene segments, including hemaglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) genes, of which the H is the main gene segment involved in determining the pathogenicity. Based on sequence analysis, avian influenza viruses can be broadly categorized into Eurasian (Europe and Asia) and North American lineages. The new H5N2 virus detected in BC contains five of eight gene segments from highly pathogenic Eurasian H5N8 virus, including the H5 gene, and three of eight segments from typical North American viruses, including the N2 gene (originating in wild birds). It was the first time a Eurasian HPAI H5 lineage virus had been a cause of outbreaks of avian influenza in domestic poultry in North America. In addition, it appears that this particular reassortant virus with Eurasian and North American avian influenza virus gene segments had not been observed anywhere before, although all eight gene segments have been identified in either Asia/Europe or North America.

3.5. Outbreak Progression and Spread

In total, 11 commercial operations (three commercial turkey, one table egg layer and seven broiler breeder) and one non-commercial mixed bird farms were infected with the H5N2 virus. These farms were located in three distinct geographical clusters.

The mode of introduction of the AI virus and the originating farm could be determined for three of these farms: IP3 and IP4 were deemed to have been infected by males from IP1 that were introduced at a time when IP1 was infectious. IP6 was contaminated by IP5 after sharing a catching crew and by being located nearby (the two IPs are separated by the private farm driveway). Links among infected farms suggesting a specific mode of transmission of the virus were not identified for any other IPs in the outbreak.

The incubation period following the movement of infected birds was reported to be 4-5 days. For all other investigations into the potential mode of introduction of the virus into an IP we used an estimate of seven days. This is based on the fact that the length of the incubation period is dependent on the dose and source of exposure. It is expected that direct contact with infected birds would lead to a higher infective dose than indirect contact, such as the presence of a contaminated service provider (NAI-HSP).

The main clinical sign observed in all infected flocks was increased mortality. Other signs included a drop in egg production and reduced water consumption. The mean time period between the appearance of clinical signs and detection was 1.4 days with a range of zero to four days. This time period decreased as the outbreak progressed, indicating the success of surveillance and tracing activities.

The following table provides a description of events associated with each IP identified during the outbreak.

Table 1: Description of events associated with each IP in the HPAI outbreak in British Columbia in 2014-2015.

| IP# | Location | Type | # Birds in affected barn | Detection (H5) Table Note 1 | Destruction Completed | Disposal (BHT Completed) | C&D Completed | Quarantine released |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chilliwack | Broiler breeder | 13,000 | Dec. 1 | Dec. 5 | Jan. 8 | Feb. 13 | Mar. 7 |

| 2 | Abbotsford | Turkey | 28,000 | Dec. 1 | Dec. 6 | Jan. 3 | Feb. 10 | Mar. 5 |

| 3 | Abbotsford | Broiler breeder | 14,000 | Dec. 3 | Dec. 7 | Dec. 28 | Jan. 16 | Feb. 7 |

| 4 | Abbotsford | Broiler breeder | 27,000 | Dec. 2 | Dec. 8 | Jan. 6 | Jan. 28 | Feb. 19 |

| 5 | Abbotsford | Turkey | 30,000 | Dec. 6 | Dec. 10 | Dec. 26 | Jan. 13 | Feb. 4 |

| 6 | Abbotsford | Turkey | 30,000 | Dec. 9 | Dec. 11 | Dec. 27 | Jan. 16 | Feb. 7 |

| 7 | Abbotsford | Broiler breeder | 18,000 | Dec. 10 | Dec. 13 | Jan. 15 | Feb. 13 | Mar. 7 |

| 8 | Abbotsford | Broiler breeder | 9,000 | Dec. 10 | Dec. 13 | Jan. 3 | Jan. 17 | Feb. 9 |

| 9 | Abbotsford | Broiler breeder | 6,000 | Dec. 10 | Dec. 14 | Jan. 6 | Jan. 21 | Feb. 12 |

| 10 | Langley | Table Egg Layer | 53,000 | Dec. 13 | Dec. 16 | Jan. 24 | Mar. 3 | Mar. 25 |

| 11 | Langley | Broiler breeder | 12,000 | Dec. 17 | Dec. 19 | Jan. 12 | Feb. 3 | Feb. 25 |

| NC-01 | Aldergrove | Non-commercial | 85 | Dec. 19 | Dec. 20 | Done at IP11 | Feb. 21 | Mar. 15 |

| NC-02 | Chilliwack | Non-commercial | 95 | Feb. 2 | Feb. 3 | Feb. 6 | Feb. 19 | Mar. 13 |

Table Notes

- Table Note 1

-

Represents the day when non-negative H5 PCR test result were obtained.

3.6. Outbreak Conclusion

On January 9th, 2015, the NEOC was deactivated. The ICP and JEOC in Abbotsford remained functional in order to support the remaining field activities required for quarantine removal and deliver post-outbreak surveillance.

On February 2nd, 2015, a second non-commercial farm of approximately 100 birds (laying hens) with HPAI was detected. Sequencing results obtained on February 7th determined that the virus involved was an H5N1. Investigation determined that this was an incidental incursion most likely from wild birds. This premises was placed under quarantine on February 2nd, 2015 and the birds were destroyed the following day. Cleaning and disinfection was completed February 19th, 2015.

On June 3rd, 2015, in accordance with Article 10.4.3.1 of the WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health Code, the province of British Columbia regained its disease-free status with regard to NAI. The WOAH was notified on June 8th, 2015.

4. Disease Control Actions

4.1. Response Infrastructure

4.1.1. The Role of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency

The AI virus is defined by the WOAH as any "type A" avian influenza virus with high pathogenicity, as well as all H5 and H7 virus subtypes. HPAI and low pathogenicity avian influenza — subtypes H5 and H7AI are federally reportable in Canada under the Health of Animals Regulations. The CFIA is the lead agency whenever a reportable animal disease is detected. Supportive roles are provided by other federal, provincial and municipal agencies, veterinary associations, and producer organizations.

4.1.2. The CFIA's Foreign Animal Disease Plans

The CFIA has developed strategies and operational plans to deal with potential incursions of foreign animal and reportable diseases. The Foreign Animal Disease Emergency Support (FADES) plan is the framework of federal-provincial cooperative agreements specifying their roles and responsibilities during an animal disease emergency. The FADES plan also describes the incident management system used to manage this outbreak.

The NAI Hazard Specific Plan (NAI-HSP) forms part of the overall plan to deal specifically with an incursion of NAI; it supplies background information on the disease itself, as well as outlines the principles of disease control and eradication, premises disinfection, and surveillance. The emergency response structure and the procedures to implement these plans are set out in the CFIA Emergency Response Plan and the CFIA Animal Health Functional Plan (AHFP).

4.1.3. Emergency Operations Centres Established

When a high-risk specimen is submitted due to evidence of a federally-reportable disease, CFIA area and national emergency response teams are alerted. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, a sequence of events is activated that put in place the control and eradication procedures described in the NAI-HSP, the AHFP, and the CFIA Emergency Response Plan. A regional and/or area emergency operations centre (REOC/AEOC) is established to coordinate the field investigation and disease control activities. In addition, a national EOC (NEOC) is established at Headquarters in Ottawa to support the field activities.

4.1.4. Incident Command Post (ICP) and Joint Emergency Operations Centre (JEOC)

An ICP and the BC Coastal Region EOC were established at the Abbotsford Animal Health District Office on December 2nd, 2014. As outlined by the BC FADES plan, the provincial and federal operations were co-located.

The BCMAGRI-AHC is a member of the Canadian Animal Health Laboratory Network (CAHLN) network of accredited laboratories. This laboratory provides specialized expertise in diagnostic poultry pathology and is the foundation for early disease detection through passive surveillance. This local laboratory was utilized to support the outbreak surveillance capacity of the CFIA.

The BCMAGRI also provided support in veterinary epidemiology, surveillance, connections with industry representatives, GIS and mapping, and requirements for disposal methods.

4.1.5. National Emergency Operations Centre

On December 2nd, 2014, the NEOC was activated at the national level. The NEOC provides support to the field activities associated with disease control and eradication policy, legal issues, communications, consultations with national producer groups, international relations and inter-provincial liaison activities

4.2. Disease Control Zoning

4.2.1. Primary Control Zone

On December 8th, 2014, the Federal Minister of Agriculture declared a primary control zone (PCZ) to prevent the spread of NAI. The PCZ included almost half of the province's 944,735 square kilometers. Within the PCZ there were three disease control sub-zones around infected farms: infected zones (1 km); restricted zones (10 km); and security zones (remainder of the PCZ).

The NAI HSP, Appendix M, lists the requirements for movement of poultry, poultry products and related materials into, within, out of, and in-transit through the PCZ.

The PCZ was revoked on March 9th, 2015.

Figure 3 - Map showing the Primary Control Zone in the HPAI outbreak in BC, 2014

Description for photo - Map showing the Primary Control Zone in the HPAI outbreak in BC, 2014

This figure includes 2 maps, the first map showing the primary control zone declared during the HPAI outbreak, 2014 in a map of Canada and the second one is showing a map of British Columbia with the same primary control zone. The primary control zone declared during the HPAI outbreak, 2014 in yellow is delimited to the north by Highway 16 shown by a red line, to the south by the Canada US border, to the east by the provincial border with Alberta and to the west by the Pacific Ocean.

4.2.2. Zones within the Primary Control Zone

4.2.2.1 Infected Zones

Given the density of flocks in a small geographic area, control efforts were prioritized within 1 km of infected farms. In total, there were 150 commercial poultry farms in the infected zones, including all of those that were depopulated.

Because there was no evidence that the HPAI virus was being transmitted by localized spread early in the outbreak, stamping-out was applied without pre-emptive culling of flocks within 1 km around infected farms. Monitoring of tracing investigations, spatial pattern of spread was implemented in order to adjust this control measure and implement the depopulation of farms within the 1-km infected zone surrounding the IPs if necessary.

4.2.2.2 Restricted Zones

A Restricted Zone (RZ) of 10 km was established around each of the 11 infected commercial farms. The RZ contained 254 commercial poultry farms in a geographical area of 7057.8 hectares (70.6 square km).

An exception was made in the case of the infected non-commercial farm (IPNC-01). A Restricted Zone was deemed unnecessary because of the farm's low poultry density, as well as its geographical isolation from the industry in the Fraser Valley.

4.3. Epidemiological Tracing

In accordance with CFIA's NAI-HSP and the WOAH's Terrestrial Animal Health Code (2014), the CFIA undertook movement tracing of all poultry, poultry products, and things exposed to poultry or poultry products associated with an infected premises during the 21-day period prior to the onset of clinical signs. This 21-day period, also known as the critical period, represents three times the maximum incubation period for avian influenza (7 days as cited by the WOAH).

The purpose of this epidemiological tracing is to:

- Identify premises at risk of having been exposed to NAI virus by either direct or indirect contact with an infected farm; and

- Identify potential sources of introduction of NAI virus to infected premises.

The CFIA's Premises Investigation Questionnaire (PIQ) was used to collect relevant epidemiological data on investigated poultry farms. Within the critical period, all direct movements of poultry on and off an IP were investigated and evaluated. Trace-in and trace-out farms with no confirmed direct contact were subjected to a qualitative risk assessment to determine the potential for transmission by indirect contact. Indirect movements were classified as low, moderate, or high risk. Decisions concerning the traced premises were made by technical specialists and approved by the Planning Section Chief with input from the NEOC. As of February 20th 2015, 110 trace investigations were completed.

4.4. Laboratory Investigation

The CFIA's NCFAD in Winnipeg is the Canadian reference laboratory for NAI virus and is responsible for diagnostic work, monitoring test and reagent performance, developing new diagnostic assays and improving upon existing assays, and test validation. The CFIA also maintains a functional relationship with a network of accredited laboratories in each province (Canadian Animal Health Surveillance Network (CAHSN)) that perform testing for specific diseases such as NAI using common protocols and reagents.

The BCMAGRI-AHC in Abbotsford, BC is a CAHSN laboratory and conducted testing of all field samples for Matrix RRT-PCR for influenza A and RRT-PCR for H5. The NCFAD completed a suite of tests to confirm and characterize the virus, including: Matrix RRT-PCR, virus isolation in eggs, RRT-PCR H5, cELISA, bELISA, HI, IVPI, Histology, IHC, and sequencing. The majority of surveillance submissions were sent to the BCMAGRI-AHC. All 13 farms (11 commercial and two non-commercial) showing positive results were declared infected.

The NCFAD typed the virus as H5N2 in the first 12 cases and H5N1 in the last. Further sequencing and analysis indicated that the H5N2 infectious agent was a reassortant virus, which contained genes from Eurasian and North American lineages of avian influenza viruses. The virus contained gene segments from the highly pathogenic Eurasian H5N8 virus, including the H5 gene, and segments from typical North American viruses, including the N2 gene. This represents the first time a Eurasian HPAI H5 lineage virus has been a cause of outbreaks of avian influenza in domestic poultry in North America.

4.5. Movement Restrictions and Permitting

Initially, in order to control movements on infected premises (IP's), official quarantines were placed on farms within 1 km of an IP and farms with an epidemiological link to an IP. Permits were issued when movements were required on these sites. Once the PCZ was established on December 8th, movement was then controlled through general and specific permits. A total of 2324 movement permits were issued by the CFIA.

4.6. Surveillance

4.6.1. Baseline Surveillance

Blood samples and oropharyngeal swabs were collected once from live birds housed on farms located in the IZ and on epidemiologically-linked farms. The swab samples were tested using matrix RT-PCR for influenza A and RRT-PCR for H5. Serum was tested to detect antibodies to avian influenza.

- For commercial farms, an oropharyngeal swab was collected from 60 birds in each barn on the premises. Blood samples were collected from 20 birds per barn.

- For non-commercial premises, an oropharyngeal swab and a blood sample was collected from 25 birds, if the flock size was 25 birds or more. For flocks with fewer than 25 birds, the CFIA collected a sample from each bird. If domestic waterfowl, such as ducks and geese, were present on site, cloacal swabs were collected instead of oropharyngeal swabs.

4.6.2. Dead Bird surveillance

Commercial poultry farms within 10 km of IPs were placed under surveillance so any spread of the disease would be quickly detected. Dead birds were collected two times per week from farms in the IZ and once per week in the RZ. The CFIA and industry associations worked together to ensure producers met the outbreak surveillance requirements.

CFIA delivered bins to farms in the control zones with instructions on participation. Dead birds were left in the bins at the farm gates on days specified by CFIA. If there was no mortality on a given sampling day, the producer was to place a bin upside-down at the farm gate. The surveillance teams stayed at the property limits. The dead birds were left behind in the bins for disposal by the producer.

The compliance level varied throughout the investigation ranging from 30% initially and ending at over 95% in February. For those producers that appeared to be non-compliant, CFIA or an industry representative would follow up with the owners of these farms to determine the cause. This procedure ended on February 24th, 2015. A total of 8392 tests were completed at BCMAGRI-AHC for this activity.

4.6.3. Flock Health & Production Records

Data on production parameters such as mortality, egg production, water and feed consumption were sent by fax or email to CFIA twice per week from all farms located in the IZ, twice per week from commercial turkey and chicken broiler breeder operations located in the RZ, and once per week from all other commercial poultry farms located in the RZ.

4.6.4. Pre-movement Surveillance

For this specific outbreak, flock health records and negative dead bird surveillance results were considered as sensitive indicators for monitoring the presence of virus in the flock. The farms that had routinely participated in this outbreak surveillance program could have a specific permit issued based on this surveillance testing.

4.6.5. Provincial Passive Surveillance

Supplemental testing was provided by BCMAGRI-AHC who initiated NAI pre-screening of all owner-submitted avian diagnostic submissions to the laboratory during the outbreak period. Oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs were taken and rRT-PCR tested on submissions originating from commercial farms. Necropsy did not proceed until the test was confirmed NAI negative. It was this type of testing that detected NCIP-01.

4.7. Depopulation and Disposal Activities

All birds on infected farms were humanely euthanized by sealing the barns and flooding them with carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. A compost pile was built within the barns to inactivate the virus by heat treatment. The compost pile (inner and outer core) must meet or exceed 37°C for six consecutive days to ensure virus inactivation. CFIA disposal specialists recorded temperatures throughout the compost pile on a daily basis. When the temperature and time parameters were achieved, the compost pile was moved outside the barn for secondary composting.

4.8. Cleaning and Disinfection of Facilities and Equipment

Once the barns were empty, the CFIA conducted an on-site assessment with the owner of each premises. This assessment determined which buildings, equipment and materials required cleaning and disinfection and potential issues with difficult items and areas.

C&D was the responsibility of the premises owner, who was required to produce a protocol detailing how the farms would be cleaned and disinfected. The CFIA reviewed and accepted the protocols. The producer contacted CFIA after the cleaning was done and if this step was approved, disinfection could begin.

Approval of the cleaning by CFIA was based on a visual verification of the removal and disposal of all dirt and organic material from the surfaces to be disinfected, as well as the disposal of contaminated items that could not be disinfected. Disinfection consisted of spraying an approved disinfectant on all areas where birds would be present when the farm was repopulated, using sufficient quantity to meet the contact time specified by the manufacturer.

4.9. Release of Quarantine on Infected Premises

The release of quarantine for previously infected farms was allowed when one of the following conditions had been met:

- The CFIA approved the C&D procedures; and

- The farms completed a 21-day fallow period

The farm was then subject to the outbreak surveillance testing requirements of the zone in which it is located.

4.10. Release of Movement Restrictions on Non-Infected farms

Movement restrictions on non-infected farms ceased when the PCZ was rescinded. The exception was for those farms located within 1 km of infected farms that had not completed C&D at the time the PCZ was rescinded, in which case the movement restriction ended upon the removal of the official quarantine on the associated IP.

4.11. Three-Month Enhanced Surveillance

Due to the outbreak of NAI in the Fraser Valley, the routine surveillance program, CanNAISS, was temporarily suspended in BC on December 8th, 2014 while an intensive outbreak surveillance program was in place. Suspending routine surveillance activity also avoids the possibility of transmitting avian influenza via the sampling program itself. Enhanced post outbreak surveillance began on March 3rd, 2015, in BC, in order to demonstrate disease-free status. During the response to the NAI outbreak in BC, CanNAISS was ongoing in other parts of the country to demonstrate continued freedom from NAI and support exports of poultry and poultry products produced.

According to the WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health Code (WOAH, 2014: Article 10.4.3), NAI-free status can be regained three months following the cleaning and disinfection of the last IP, meaning the time period for the enhanced surveillance was March 3rd, 2015 to June 3rd, 2015.

Of the 848 poultry farms registered in the Province, 368 broiler farms and five hatcheries without birds were removed from the sampling plan, as surveillance normally targets older birds. 180 non-commercial farms were also removed from the sampling plan as they were not commercial poultry. This left 295 eligible farms for testing. 67 of these farms either had no birds on premises or the birds were too young. As a result, these farms were not available for test.

A total of 228 farms and 2,166 samples were tested with negative results for H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses, representing 91% of breeder farms, 84% of table eggs, ducks, geese or specialty chicken farms, and 49% of commercial turkey farms in the BC poultry industry.

After the three-month enhanced surveillance period, CanNAISS returned to normal activities in BC.

4.12. HPAI Freedom declaration

In accordance with the guidelines in the WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health Code (2014), freedom from NAI was declared on June 3rd, 2015, three months following the approval of the last cleaning and disinfection. The Province of BC officially regained its NAI-free status and the WOAH was notified on June 8th, 2015.

5. Summary of Findings and Working Hypotheses on Source and Transmission of NAI

5.1. Source of the Virus

Waterfowl are well established primary reservoirs for a wide variety of strains of avian influenza. A recent report from the CFIA entitled "Qualitative Risk Assessment of a Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Canada" examined multiple potential sources of the H5N2 virus. The epidemiological data currently available suggest that migratory wild birds within the Pacific Flyway may be the source of introduction of the new HPAI H5N2 virus into the Fraser Valley. This hypothesis is supported by the mid-December 2014 detection of H5N2 in a non-commercial operation (IPNC-01) where birds were known to have shared a pond with wild waterfowl. Also, H5N2 was detected in Whatcom County in Washington State, (close to the border with BC) in a Northern pintail duck in December, 2014. The H5N2 virus, similar to the one involved in the outbreak in BC, was detected in non-commercial operations in Washington State in 2014 and 2015, and Oregon in 2015. The virus has also been reported in wild migratory birds and captive wild birds in several other Western states in the USA in 2014 and 2015.

In January 2015, an HPAI H5N1 of Eurasian/North American origin was identified again in Washington State. The same virus was then detected on February 7th, 2015 in a non-commercial operation in BC. In the Fraser Valley during the fall, tens of thousands of migrating waterfowl use the farm lands of the region as a resting stop before continuing their journey southward. This fall migration period usually coincides with high rainfall and this was the situation in 2014. In addition, December recorded higher-than-normal average temperatures and rainfall, which is associated with a higher-than-normal number of wild migratory birds still present in the region. On many of the infected farms, standing water and large numbers of waterfowl were observed in the fields.

5.2. Secondary Spread

Waterfowl contaminate the environment by shedding the virus in their feces. The likelihood of exposure to indoor-reared poultry by migrating waterfowl is subject to several factors: the density of the poultry population in the affected area, the strength of biosecurity measures, the level and frequency of contact between farm workers and birds, and the proximity of the poultry to the migration routes of wild birds. While poultry production systems in Canada are designed to reduce or prevent contact between wild birds and commercial poultry, the potential does exist for the introduction of the virus from the environment if a breach in biosecurity occurs.

Once a poultry barn has become infected by HPAI, the viral load produced by thousands of infected birds makes the spread within and between farms much more difficult to control. Yet, in this outbreak, very little localized spread of the virus was observed. Most new infected farms were many kilometers away from each other, even in high density areas. The introduction of mandatory biosecurity programs in the poultry industry seems to account for some of this. As well, the CFIA detects, depopulates and disposes of infected poultry in barns in less than half the time required in 2004, and surveillance practices limited on-farm traffic. These factors likely contributed to reducing local disease transmission around IPs in the Fraser Valley during this outbreak.

5.3. Field Epidemiology – Summary of Findings

Seven of the 11 commercial farms infected over the first three weeks in December were broiler breeder operations. It was determined that two farms likely became infected via the transfer of breeding stock (spiker males) from IP1 to IP3 and IP4 during the infectious period of IP1. Service provider information indicates that infection of IP6 by IP5 was probably due to sharing a catching crew that did not apply biosecurity measures before going to IP6. All other contacts examined did not help identify how the virus spread; there were no links among IPs that suggested spread via direct or indirect contact.

A review of the preliminary field epidemiological investigation identified three hypotheses related to the means of introduction and spread of HPAI virus during this outbreak:

- There were at least four independent primary introductions of HPAI virus into commercial farms during this outbreak (IP1, IP2, IP5 and IP9). This hypothesis was supported by the distance and absence of any identified epidemiological links between the farms (they were located at least 10 km apart).

- Each of these point source infections led to limited local spread, with possible breaches in biosecurity, particularly the presence of rodents and contact with infected premises or wild birds as major risk factors.

- Secondary spread of virus between farms may have occurred due to the high density of farms in this particular geographic area as well as the proximity to waterfowl. Local contact events with people, vehicles, machinery, vermin, dust particles could be responsible for this.

Figure 4 - Hypothesized spread of HPAI among commercial farms in the 2014 outbreak in BC resulting from the analysis of field epidemiological data. IPs in bold represent potential point source introductions.

Description for photo - Hypothesized spread of HPAI among commercial farms in the 2014 outbreak in BC resulting from the analysis of field epidemiological data. IPs in bold represent potential point source introductions

This diagram shows the hypothesized links among the different infected farms (represented by IP) during the outbreak that result from the epidemiological investigation.

The diagram shows IP1 in bold, a broiler breeder producer, with two solid arrows to IP3 and IP4 representing confirmed links to these two broiler breeder producers. The bolded character for IP1 means that it is considered to have been infected as a point source introduction. IP3 and IP4 are considered to have been infected as a result of the movement of live birds.

To the right, IP2 is a meat turkey producer, is also shown in bold as it is also considered a point source introduction. Two dashed arrows point from IP2 to IP7 and IP8 who are broiler breeder producers. Dashed arrows represent suspected links and the image refers to local spread or environmental contamination as a means of spread from IP2.

Below IP1 we find IP5, a meat turkey producer, in bold, representing a point source introduction. A solid arrow points from IP5 to IP6 (also a meat turkey producer) representing spread through a shared catching crew and close proximity (they shared a driveway).

Dashed arrows leave IP5 and IP6 and point to IP10 representing the suspected link through airborne spread or local spread. IP10 is a table egg producer. Another dashed arrow leaves IP10 to IP11, a broiler breeder producer representing local or environmental spread.

Finally, at the bottom right of the diagram we find IP9 in bold representing a point source introduction. It has no links to other infected farms.

Field epidemiology investigations after December 16th did not identify any links between the IPs. Farm workers on commercial IPs did not own birds or did not work on other commercial poultry farms. Indirect contacts account for no links between the two sectors and there were no movements of birds from the commercial IPs to the non-commercial IPs.

5.4. Airborne Spread Investigation – Summary of Findings

Airborne spread was suspected as an important mode of transmission in the 2004 HPAI outbreak in BC (Power, 2005). An epidemiological investigation into this pattern was conducted with risk factors of wind speed and direction, level of precipitation and location of farms in relation to an IP (at levels of 1.5 and 3 km) being examined. Following this investigation, there was no significant evidence of this being a source of spread in this outbreak.

The likelihood of airborne spread during specific depopulation events was also assessed using the same methodology as described above but for the specific time period when depopulation events took place. It was estimated that the likelihood of specific depopulation events being responsible for contamination was very low to low.

5.5. Viral Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis – Summary of Findings

Full genome sequencing was performed on the original specimens and on the viruses isolated from those specimens for each of the infected farm. The sequencing indicated that no significant changes had occurred as a result of passaging in chicken embryos.

The viral sequencing demonstrated a very high degree of homology between the IP's. Additionally, there was evidence that this strain was circulating as a well-adapted highly pathogenic strain in the wild bird population rather than a low pathogenic strain which mutated into a highly pathogenic strain.

5.6. Wild Bird Surveillance – Summary of Findings

In partnership with the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) and the BCMAGRI-AHC, the BC Wild Bird Mortality Investigation Plan provided an established infrastructure for the public reporting, triage and collection of dead wild birds. The program was immediately enhanced to define target species (waterfowl, raptors, herons) and to provide a field collection and carcass retrieval service provided by a private contractor. In addition, Fraser Valley poultry producers were encouraged to submit dead wild birds found in close proximity to their barns. Between December 1st and February 18th, 2015, a total of 125 wild birds in the Fraser Valley were tested for Avian Influenza by RT-PCR and matrix positive swabs were further tested for H5 and H7. All positive detections were forwarded to NCFAD for further characterization. Of these samples, one wild bird (duck) was found to be positive for H5N8.

6. Communications

Daily inter-agency briefings held at the JEOC included CFIA staff, section leads and representatives from provincial and municipal governments, public health agencies, and industry groups. The CFIA's JEOC Information Officer worked with the BC Emergency Management Program lead to develop messaging for municipalities, First Nation groups and other governmental agencies. The Information Officer also worked with the BC poultry industry spokesperson to coordinate media responses, and industry briefings to ensure consistency of messaging for media queries and agency updates.

7. The Role of Poultry Organizations

Since previous avian influenza events in BC, industry and the BCMAGRI have worked collaboratively to improve premises identification. A secure central database has been created that contains accurate premises and sub-premises (barn or production floor) identification and contact information for all poultry farms in the regulated marketing system.

The poultry industry in BC provided data to support GIS mapping and outbreak and post-outbreak surveillance protocols. Industry representatives facilitated the flow of information. They also supported the field epidemiology team by providing contact information for service providers and facilitating responses to inquiries.

- Date modified: