National Farm and Facility Level Biosecurity User Guide for the Equine Sector

Table of Contents

- Section 1: Glossary

- Section 2: Introduction and background

- Section 3: Farm and facility specific biosecurity plan

- Section 4: Principles of infection prevention and control programs

- Section 5: Preventive horse health management program

- Section 6: New horses, returning horses, visiting horses, movements and transportation

- Section 7: Access management

- Section 8: Farm and facility management

- Section 9: Biosecurity awareness, education and training

- Section 10: Farm and facility location, design, layout and renovations to existing facilities

- Annex 1: Development of the user guide and acknowledgements

- Annex 2: Important infectious diseases of horses in Canada

- Annex 3: Self-evaluation checklist for risk assessment

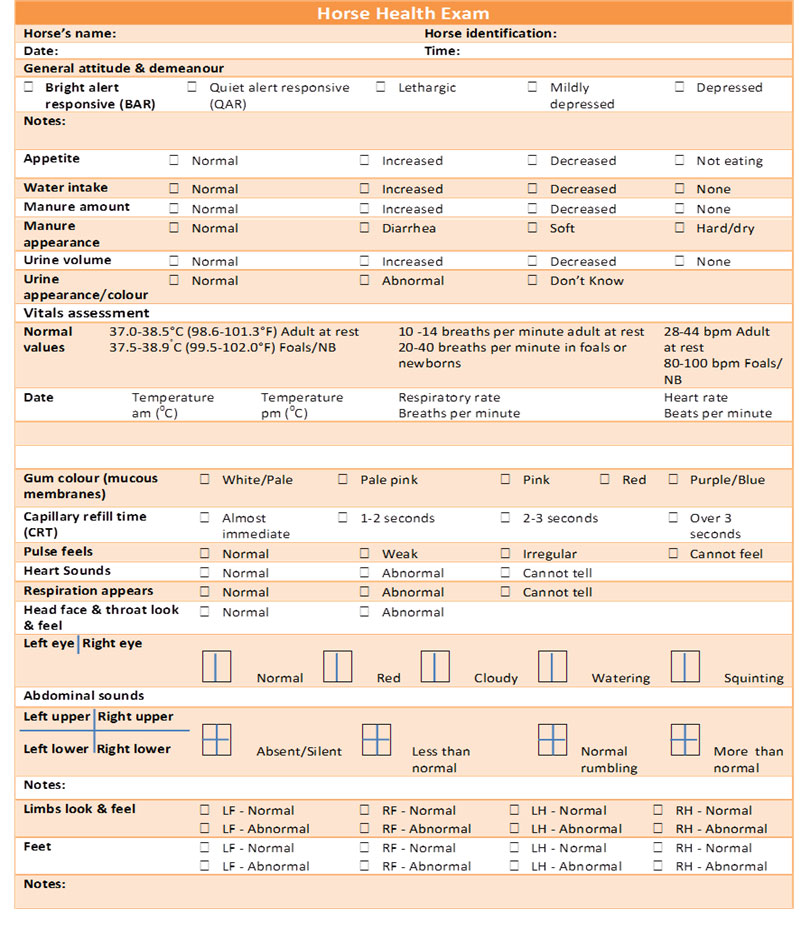

- Annex 4: Conducting a horse health check

- Annex 5: Horse Health Exam Record

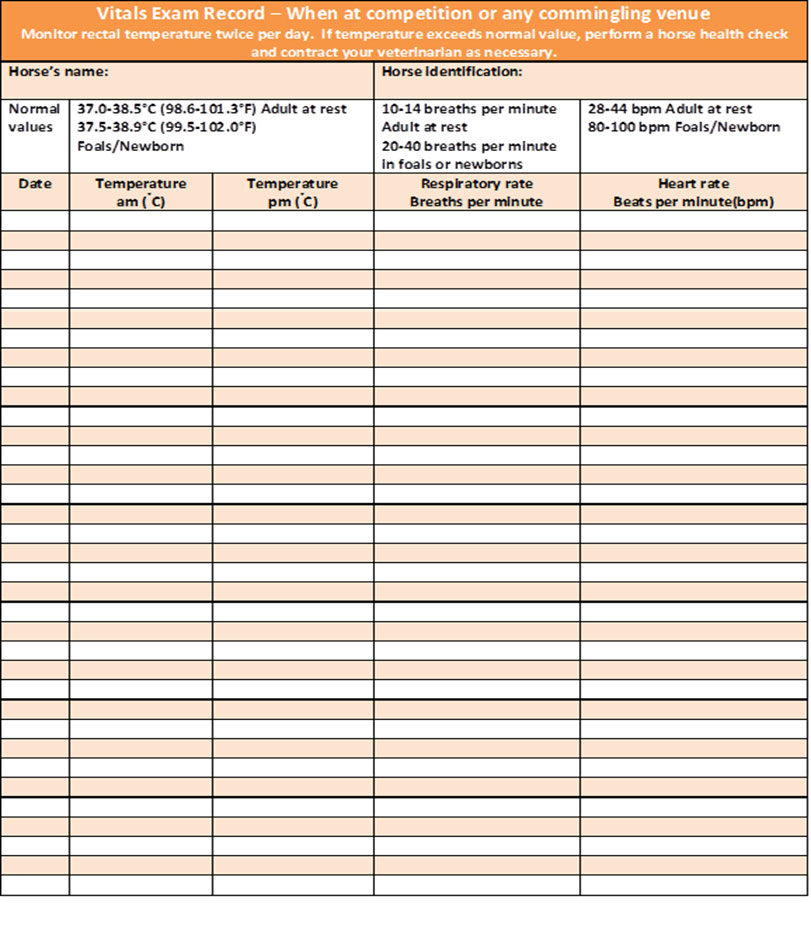

- Annex 6: Vitals Exam Record

- Annex 7: Sample horse event participant declaration

- Annex 8: Sample letter to participant

- Annex 9: Incoming horse protocol and checklist

- Annex 10: Additional guidance on vaccination

- Annex 11: Additional guidance on parasite control programs

- Annex 12: Important gastro-intestinal nematode parasites of horses in Canada

- Annex 13: Separating sick horses

- Annex 14: Selected disinfectants

- Annex 15: Cleaning and disinfecting procedures

Section 1: Glossary

- Access management:

-

Controlling the movement of horses, equipment, vehicles, and people on-and-off a farm or facility, as well as movement between different areas of a farm or facility to minimize the transmission of pathogens. It may include physical barriers (for example, fencing and gates that clearly indicate entry and exit points) and/or procedural measures (for example, hand washing, boot cleaning and disinfection).

- Aerosol:

-

Solid or liquid particles suspended in air that can be distributed over short distances.

- Best practices:

-

For this document a best practice is a program, process, strategy, or activity that has been shown to be most effective in preventing and controlling disease. Best practices may have to be modified before implementation to accommodate a specific farm or facility and enhance practicality.

- Bio-exclusion:

-

A set of practices to minimize the introduction of pathogens into a population of animals from an outside source.

- Bio-containment:

-

A set of practices to minimize the release of pathogens from a population of animals in a particular location (for example, a farm or facility).

- Bio-management:

-

A set of practices to minimize the transmission of pathogens within a population of animals (for example, the spread of disease among horses within a farm or facility).

- Biosecurity:

-

A set of practices used to minimize the transmission of pathogens and pests in animal and plant populations including their introduction (bio-exclusion), spread within the populations (bio-management), and release (bio-containment).

- Biosecurity zone:

-

A defined area on a farm or facility established by natural or man-made physical barriers and/or the use of biosecurity procedures designed to reduce the transmission of pathogens (for example, a controlled access zone and/or restricted access zone).

- Closed herd:

-

A population of animals that remains distinct by preventing the introduction of new animals from external sources, maintains their own breeding stock, and prevents direct contact with other herds of similar species.

- Commingle:

-

Where horses from different locations or a different health status are brought together and exposed to each other, either directly or indirectly; may be short or long term. Some examples of commingling sites include boarding stables, auctions, summer pastures, staging sites, horse shows, rodeos, 4-H events, and horse clinics.

- Controlled access point (CAP):

-

A designated and visually defined entry point to a horse farm or facility, a controlled access zone or restricted access zone to manage the traffic flow of people, horses, vehicles, equipment and materials.

- Controlled access zone (CAZ):

-

A designated area that contains the land, buildings, equipment and infrastructure involved in the care and management of horses where access and movements are controlled. Entry is restricted and managed through a controlled access point. The controlled access zone is often the first zone that is entered on a farm or facility and frequently includes laneways, equipment, storage sheds, and riding arenas, although some of these may be in the restricted access zone in other facilities. It usually excludes the house and office space of the farm owner and/or manager. The controlled access zone may include pastures and barns that horses are not currently occupying. A controlled access zone has its own specific biosecurity protocol and often encompasses the restricted access zone(s).

- Custodian:

-

Any person who has control of horses and is responsible for their care, whether on a short-term or long-term basis. This may include owners, stable owners and staff, volunteers, clients, service providers and family members.

- Disease:

-

A change from the normal state. A deviation or disruption in the structure or function of a tissue, organ or part of a living animal's body.

- Disinfection:

-

The process that is used to inactivate, decrease or eliminate pathogens from a surface or object.

- Direct contact:

-

Close physical contact between animals (for example, nose to nose, social interaction or breeding).

- Emerging disease:

-

A new infection resulting from the evolution or change of an existing pathogen or parasite resulting in a change of host range, vector, pathogenicity or strain; or the occurrence of a previously unrecognized infection or disease.

- Endemic disease:

-

The continued presence of a disease in a specific population or area usually at the same level - often a low level. In animals, it is sometimes referred to as enzootic disease.

- Event:

-

An organized gathering of horses from two or more farms or facilities for a set amount of time. A horse event or activity is defined as any market, sales or auction, fair, parade, race, horse show, meeting, recreational activity, demonstration or clinic, rodeo, competition, or any other horse gathering.

- Foreign animal disease:

-

An existing or emerging animal disease that poses a severe threat to animal health, the economy, and/or human health that is not usually present in the country.

- Facility:

-

A defined area of land and all associated buildings used primarily for the short-term care and maintenance of horses for commercial purposes and events where commingling is common (for example, competition grounds, race tracks and auction markets).

- Farm:

-

A defined area of land and all associated buildings used primarily for the long-term care and maintenance of horses (for example, boarding stables, breeding farms and riding centres).

- Federal reportable disease:

-

Refers to diseases in federal and/or provincial acts and regulations. Federally reportable diseases are outlined in the Health of Animals Act and Reportable Diseases Regulations and are usually of significant importance to human or animal health or to the Canadian economy. Animal owners, veterinarians and laboratories are required to immediately report the presence of an animal that is contaminated or suspected of being contaminated with one of these diseases to a Canadian Food Inspection Agency district veterinarian. Control or eradication measures may be applied immediately. A list of federally reportable diseases is available on the CFIA website.

- Fomite:

-

Any inanimate object or substance, such as clothing, footwear, equipment, tack, water or feed that mechanically transmits a pathogen from one individual to another.

- Health status:

-

Current state of health of the animal or herd, including both its condition and the presence of pathogens in the animal or herd. Information used to establish the health status includes the disease history and the results of any diagnostic testing, herd health management practices, vaccination and deworming protocols in sufficient detail to determine compatibility with the resident herd, and housing and movement detail sufficient to identify any potential recent disease exposure.

- Horse:

-

Refers to all domestic equine species, namely horses, ponies, miniature horses, donkeys, mules and hinnies.

- Immediately notifiable disease:

-

In general, immediately notifiable diseases are diseases exotic to Canada for which there are no control or eradication programs and are to be reported immediately to a specific government agency.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency can undertake control measures for such diseases when notified of their presence in Canada. This category also includes some rare indigenous diseases. A herd or flock of origin must be certified as being free from these diseases in order to meet import requirements of trading partners. Some provincial ministries may require notification for surveillance and/or control of certain immediately notifiable diseases.

- Indirect contact:

-

Refers to contact with a pathogen without directly coming into contact with the source (for example, aerosol or contaminated fomites).

- Infection:

-

The invasion and multiplication or reproduction of pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites in the tissues of a living animal.

- Infectious disease:

-

Disease caused by pathogens (for example, parasites, bacteria, viruses, fungi or prions).

- Medical waste:

-

Waste generated by administration of treatments (for example, needles, syringes, expired medications, and disposable materials used in the treatment of horses).

- Mode of transmission:

-

The method whereby pathogens are transmitted from one animal or place to another. An example of direct transmission is nose-to-nose contact. Examples of indirect transmission may include contact with contaminated bodily fluids, vectors or fomites.

- Monitoring:

-

This refers to the systematic observation and recording of clinical signs that reflect the health parameters of the horse (for example, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, for mental status [responsive and alert], for gait and posture [normal, coordinated, not lame], for body condition [thin, normal, obese]). The level of monitoring is dependent on the health status of the horse.

- Mortality:

-

A measure of the number of deaths in a population.

- Normal carrier or subclinical carrier:

-

A horse that displays no signs of sickness but is harbouring a pathogen.

- Pathogenicity:

-

The ability or capacity of a pathogen to cause disease in a living organism.

- Pathogens:

-

Bacteria (including mycoplasma), viruses, fungi, parasites and other microorganisms that can cause disease.

- Peer group:

-

Horses of similar age (for example, yearlings), use (for example, broodmares and school horses), or health status (for example, same preventive health program).

- Personal protective equipment (PPE):

-

Refers to specialized clothing and equipment worn by an individual to provide a protective barrier against exposure and injury from hazards. It can be used to protect against pathogens, chemicals (disinfectants and medications) and physical hazards (from needles or bites), however the specifications of the equipment are different for each hazard. For infectious diseases, personal protective equipment includes coveralls, boots, boot covers, gloves, and in some instances, face shields and respirators that protect skin, mucous membranes and airways from pathogens. Personal protective equipment also reduces the transmission of pathogens to other horses from contaminated clothing, equipment and dirty hands.

- Pests:

-

Includes insects, spiders, ticks, rodents, birds and other animals that pose a nuisance to horses.

- Physical barriers:

-

The use of physical structures and items to minimize exposure to pathogens. This includes the use of fences and gates to manage access and traffic flow and solid pen partitions to minimize contact between horses. It also includes the use of protective clothing, boots and gloves that provide a barrier to contamination and/or infection of a person.

- Procedural measures:

-

The use of processes such as hand washing, cleaning and disinfection to minimize the transmission of pathogens, procedures for assessing the health status of new horses and vaccination to protect horse health.

- Provincial reportable/notifiable diseases:

-

Some provincial agriculture departments require reporting of diseases outlined in their provincial animal disease legislation. For additional information, contact the respective provincial agriculture department.

- Restricted access zone (RAZ):

-

A designated area where horses commonly reside (are stabled, housed, pastured) and where access by people, equipment and materials is further restricted. The zone(s) include the pens, barns, and pastures, as well as separation areas used for new, visiting and sick horses. The layout and management practices of individual farms and facilities will determine whether manure storage and other production infrastructure directly involved in animal care and maintenance should be included within the restricted access zone.

- Risk:

-

The likelihood of an unfavorable event occurring and affecting health.

Examples of high and low risk

- Event

- High-risk event - A horse auction/sale poses a high risk to horse health when there are no disease prevention requirements and protocols in place, and there are a high number of horses from multiple locations commingling.

- Low-risk event - An event such as the Pan-Am equine games poses a low risk to horse health where high level, healthy equine athletes are subject to strict biosecurity protocols, including testing and vaccination requirements prior to arrival, and regular monitoring by specially appointed equine veterinarians.

- Horses - Can pose a risk for spreading disease and/or be at risk of acquiring disease.

- Higher risk or high-risk horse for transmitting disease: Horses that are a higher risk for harbouring and transmitting pathogens. This includes horses that are: visibly sick (clinical infection), infected but not showing signs of sickness (subclinical infection), known to have been exposed to sick horses, and those that have recently recovered from sickness.

- Higher risk or high risk of becoming infected or sick - A young horse which has little immunity to disease and is at a higher risk of becoming infected or sick. The lack of immunity may result from not being vaccinated, being improperly vaccinated, and/or having little previous exposure to small numbers of pathogens from other horses (which may occur when raised in a closed herd). Any horse that is debilitated, stressed, malnourished, dehydrated, very young, very old, one with a long-standing or underlying health issue would be at high risk. If these horses are then exposed to a high-risk event where there is exposure to many other horses of varying health status, they may become sick.

- Lower risk or low-risk horse for transmitting disease or becoming infected or sick - Horses that are healthy, well vaccinated, well-nourished and managed under a herd health program and rarely travel or are rarely exposed to horses of different health status are a low risk or a lower risk for transmitting disease or becoming infected or sick when exposed to pathogens.

- Event

- Sanitize:

-

A process that reduces the number of pathogens without completely eliminating all microbial forms on a surface.

- Separation:

-

Using physical barriers or distance to prevent direct contact between horses. Separation is a management tool to minimize the risk of introduction and spread of disease. Other terminology such as isolation and quarantine is commonly used for specific purposes of separation

- Quarantine: A process of separating an animal(s) and restricting movement of the animal; it can be considered a "state of enforced isolation". Frequently, it is a regulatory approach to separate horses to establish and maintain a desired health status.

- Isolation: The process of separating animals that are sick, suspected to be sick, or of an unknown or lesser health status from healthy animals. The period of separation ends when animals have recovered, or been determined to be healthy, or aligned with the health status of the herd. Separation includes measures to prevent direct contact (nose-to-nose) and indirect contact (shared equipment) between isolated animals and the remainder of the herd.

- Sharps:

-

Common medical items including needles, scalpels, scissors, staples, and other objects capable of puncturing or cutting skin.

- Sharps container:

-

A container used to safely store used needles and other sharps for disposal. Only "approved" sharps containers should be used, as they are designed to prevent injuries by being puncture resistant and to prevent spillage or removal of disposed items.

- Shedding:

-

Transmission of an infectious agent from an animal to another animal or to the environment; can occur in the absence of clinical signs.

- Standard operating procedure (SOP):

-

A defined and documented procedure to be followed, detailing the steps to be taken to meet an objective. This includes any formal process that a custodian uses to define how they manage their operations on a day to day basis. The protocol may be formally documented or a non-documented process that is strictly followed. The intent is to focus on the process rather than the documentation.

- Susceptible host:

-

A person or animal who lacks the immunity or ability to resist the invasion of pathogens which then multiply or reproduce resulting in infection.

- Vector:

-

An organism such as a mosquito, fly, flea, tick, rodent, animal or person that transmits pathogens from an infected host (a horse) to another animal. A biological vector is one in which the pathogen develops or multiplies in the vector's body before becoming infective to the recipient animal. A mechanical vector is one which transmits an infective organism from one host to another but which is not essential to the life cycle of the pathogen.

- Wildlife:

-

All undomesticated animals (fauna) living freely in their natural habitat. Wildlife may come into occasional inadvertent contact with domestic horses on their farm or facility.

- Zoonotic disease:

-

A disease caused by pathogens that can occur in both animals and humans (for example, Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] and Salmonella sp.).

Section 2: Introduction and background

Biosecurity: Cost-effective health insurance for your horse and all of Canada's horses

This biosecurity user guide supports the national biosecurity standard. It provides greater detail and practical information on specific biosecurity measures at the farm and facility level, including tools to assist horse owners and custodians in developing and implementing biosecurity. The guide is organized using the same framework as the biosecurity standard. (Refer to Annex 1 for information on development of the user guide).

Infectious diseases of horses are a common occurrence and are a reality that horse owners and custodians must face. As a horse owner or custodian, you care about and are ultimately responsible for ensuring the health and welfare of your horse(s). The choices you make (whether selecting a boarding stable, locations for riding or the competitions/events you wish to attend) affect the disease risks your horse(s) are exposed to and your ability to provide for and protect their health and well-being.

Biosecurity can manage disease risks

2.1 What is biosecurity?

Biosecurity is a set of measures used to protect horse health by reducing the spread of contagious diseases and pests.

Biosecurity is: "A set of practices used to minimize the transmission of pathogens and pests in animal and plant populations, including their introduction (bio-exclusion), spread within the populations (bio-management), and release (bio-containment)."

Good biosecurity is practiced every day, not only in the event of a disease outbreak. Biosecurity practices are difficult to "ramp-up" if not already a part of the daily routine. The level of biosecurity required often depends on the size of an operation, the venue and risks that are present. For example, biosecurity considerations at a large international show or racetrack with a large population of visiting horses are more complex than those needed at a small stable where horses seldom travel.

The threat of infectious disease is always present. Ideally, biosecurity would eliminate disease threats by preventing exposure to pathogens and their spread. Eliminating all threats is impractical and rarely achievable, therefore, at the farm level think of biosecurity as risk management.

Biosecurity requires balancing the:

- risk of disease transmission;

- consequences of disease occurring; and

- measures required to minimize disease.

As a horse owner or custodian, your tolerance for disease risk likely varies from other horse owners. Similarly, farm and facility owners and managers may have different disease risk tolerances depending on the use of their property and the clientele (boarders or participants) they may serve. It is important to recognize these different disease risk tolerances because it influences the:

- extent of the biosecurity measures that are implemented on farms and facilities; and

- willingness of horse owners and custodians to implement and comply with biosecurity measures.

Biosecurity measures need to be tailored to the needs of individual farms and facilities. The plans should be developed with the assistance of the attending veterinarian taking into account your goals, management practices, and the internal and external disease threats. Biosecurity plans must be understood, practical, achievable and sustainable. Because the consequences of disease are many and far reaching you should not look at your biosecurity practices and risk tolerance without considering the rest of the industry.

10 Biosecurity considerations for all horse owners and custodians

- Apply biosecurity every day and not just during a disease outbreak.

- Work with your veterinarian to develop an infection control plan that is right for your horse(s) and farm or facility.

- Define the biosecurity needs and take steps to reduce the risk of disease introduction and spread.

- When doing a risk assessment, consider the level of risk you are willing to tolerate on your farm, facility or property. For example, an active training stable of healthy adult horses can have very different needs than a breeding facility that houses foals at high risk for serious disease if exposed to certain pathogens. The focus of all farms and facilities should be to reduce the occurrence and impact of disease rather than complete prevention.

- Recognize that horses and humans are not the only biosecurity risk to your herd. Minimize the presence of rodents and insects by keeping feed secure and eliminating standing water.

- Vaccinate your horses against disease risks. Vaccination is one of the pillars of biosecurity, which will help in reducing the risk of infection for specific diseases.

- Do not use communal water sources or share equipment, and keep your horse(s) under your control (when around unfamiliar horses).

- Ask people to wash their hands before handling your horse for any reason.

- When transporting horses or housing them in stalls away from home, clean and disinfect stalls prior to introducing the horse to its "home away from home."

- Monitor your horse daily for clinical signs that may result from an infectious disease such as reduced appetite, depression, fever, nasal discharge, coughing, diarrhea, or acute onset of neurologic distress. Know how to take your horse's temperature and learn what their normal is (normal for adult horses can range from 37.0-38.5°C [98.6-101.3°F]). Having a baseline will help recognize when something is wrong. When in doubt, call your veterinarian!

Spot the biosecurity concerns

Everything changes over time, including the way we interact with our surroundings. We grow accustomed to our own environments and this familiarity can reduce critical observation. Issues that may be important can be overlooked: the deteriorating fence, water runoff from spring thaws and summer rains, and broken or missing equipment. It is important to critically examine the routine tasks and details on your horse farm or facility as they play a vital role in managing disease.

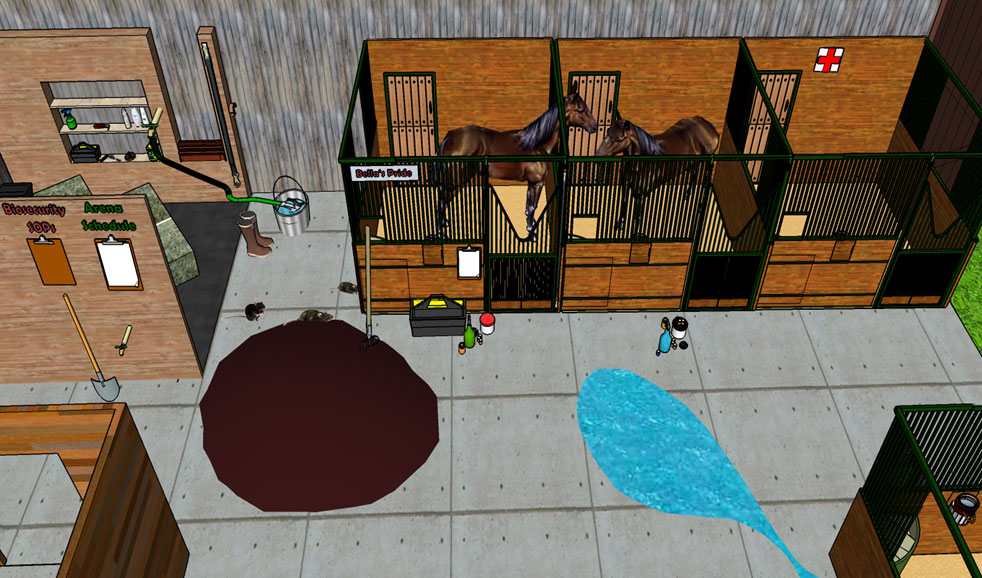

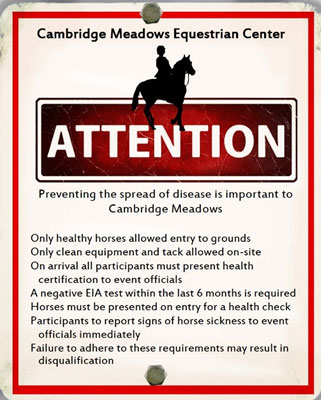

The following pictures depict a small horse farm with a number of biosecurity concerns that are not being managed. Before reading this guide, take some time to identify as many biosecurity issues as you can. After reading the guide, review the diagrams again to determine if there are any issues that you have missed. Answers are provided below each diagram.

Figure 1: Identify the biosecurity concerns

There are a number of biosecurity concerns on this property. How many can you identify?

Description for image – Figure 1: Identify the biosecurity concerns

a picture of a small horse farm. The horse area is located on the front portion of the property and is separated from the house which sits behind it by a wooden fence painted white. The gate to the farm is open and there is a large sign next to the gate that states: "Majestic Manes Ranch. Everyone Welcome. If you can sit you can ride." The farm is primarily grass, a few trees and in the center of the property is a small pond that extends into the property the house is on. There are multiple horses on the property. There is one horse next to the pond that is lying on its side and appears to be dead. There is a coyote standing near the front gate. There are a number of trailers and pick-up trucks scattered throughout the property in a disorderly fashion. There is a wooden horse barn on the right side, the doors to it are open and a large stack of hay bales is sitting in front of it. There are number of large metal drums stacked next to the barn as well as a large pile of manure with a pitchfork sticking out of it. There is a wheelbarrow filled with manure next to the hay bales.

Biosecurity concerns

- Access: There is little to protect horses on this farm from diseases that may be transmitted by people and equipment contaminated by pathogens and sick horses. The farm gate is not secured, the barn doors are open and no biosecurity zones or biosecurity signage is present. The farm sign encourages visitor entry and provides no guidance on what biosecurity procedures, if any, are required. No owner contact information is provided for visitors seeking guidance. There is no designated area for visitor parking; vehicles and trailers are parked in various locations in horse pasture and adjacent to the barn.

- Traffic Flow: There are no laneways or pathways onsite to manage the traffic flow of people and animals. There are no paved surfaces aside of the barn floor. Wet conditions will result in tracking mud, manure and other debris into and out of areas. It will be difficult to minimize the spread of disease without clean, hard-surfaced pathways for movements.

- Wildlife and pest control: A coyote is visible near the front of the property. There are some manure piles on the property and some barrels adjacent to the barn, and this may provide habitat for rodents, insects and other pests. Vehicles and livestock trailers may also provide secure habitat for some pests.

- Feed and water: Feed and water sources are not protected from contamination. Hay bales are stacked outside providing access to horses, other livestock and wildlife. Horses have access to pond water, which can be contaminated by wildlife, horses and runoff from manure piles.

- Manure: Manure can be a source of pathogens, can contaminate feed and water sources and can provide a breeding site for insects. Manure is improperly stored: there is a large pile adjacent to the barn and a smaller pile in the horse pasture. There is a wheelbarrow with manure in it close to the stacked hay. Ideally manure should be composted and stored to prevent access by pests, wildlife and horses.

- There is no ability to separate horses outside, no turn-out pens and only one fenced outdoor area that all horses share. One horse appears to have died and has not been properly disposed of.

Figure 2: Identify the biosecurity concerns

There are a number of biosecurity issues in this barn, look carefully and identify them.

Description for image – Figure 2: Identify the biosecurity concerns

The picture is of the inside of a small wooden horse barn with a concrete floor. In the middle of the floor is a large pile of manure, a water puddle and a number of mice or rats can be seen. There are four horse stalls; three of the stalls are on the back wall and two of the stalls contain horses. The other horse stall is on the bottom wall close to the door. There is a wash stall on the left rear wall of the barn which has a few bales of hay on the floor, a pair of boots in front of it and a bucket of water with a hose in it.

On the outside of the wash stall are some clipboards and some tools. On the ground in front of the stalls containing horses are some toolboxes and bottles of medication.

Biosecurity concerns

- Horse stalls permit direct contact with neighbouring stall mates - one horse is taking full advantage of this.

- The stall designated for sick horses (first stall on the far side) permits contact with healthy horses. The location of this stall near the entrance places it in heavy traffic flow allowing unnecessary contact and exposure to people and horses entering and exiting the barn.

- Only one of the horses has any identification information posted on the stall (Bella's Pride). Additional records are posted on a clipboard near the stall door. The horse in pen 2 has no identification or records posted.

- There are no biosecurity standard operating procedures (SOPs) posted - the clipboard is empty; however, an arena riding schedule is present. Arena schedules are a good biosecurity practice as they can help to minimize interactions between horses; however, it likely offers little benefit on this site.

- Pooling water is present and manure is piled in the alleyway of the barn. These are attractants for pests and can be a source of pathogens. Horses can be exposed when being moved from their stalls and by owners or custodians walking through the barn and into horse stalls. Pests are present - rodents are visible near the manure pile and wash stall.

- Hay is improperly stored on the floor of the wash stall, preventing use of the stall and allowing contamination of the feed. Feed also serves as an attractant for rodents.

- Horse medications and materials are improperly stored and left on the floor of the barn outside the stalls. Not only does this increase the opportunity for them to be contaminated, it may affect their efficacy and it poses a safety hazard for pets and children.

- The hose submerged in the water bucket can become contaminated if the bucket belongs to a sick horse. Disease can then be spread to other horses when filling their water buckets.

- A pair of rubber boots is present which is a good biosecurity practice; however, no other outer clothing/cover-ups/coveralls are present.

- Doors to the barn are open, which may present a risk for access.

2.2 Why is equine biosecurity important?

Infectious disease in horses continues to rank as one of the major challenges to the equine industry, leading to sickness (and potentially death), financial costs, welfare concerns and potential risks to human health. Measures to reduce the occurrence and severity of disease in the Canadian herd are important as disease risks change locally and globally.

Goals of the user guide: To assist horse owners and custodians in protecting the health and welfare of their horses by supporting the implementation of biosecurity on all horse farms and facilities in Canada.

Goals of the national standard:

- To assist horse owners and custodians in protecting the health and welfare of their horses by minimizing the transmission of contagious diseases and reducing the frequency and severity of disease if infection occurs.

- To achieve a Canadian national herd that has a high health status with horses in good condition, with strong immunity to pathogens and an overall decrease in the number of pathogens.

- To maintain a country that is eligible to export horses worldwide.

The impacts of infectious disease in horses are significant and can be devastating. Disease can range from mild sickness to death, from occasional cases to extensive disease outbreaks. Even mild disease can result in permanent damage and impaired function. Farms and facilities with poor biosecurity may become a significant risk to the rest of the industry. It is important that every horse farm and facility develops and implements a biosecurity plan.

Some equine diseases can spread quickly, particularly in populations of horses that have never been exposed or developed resistance to the disease. An example of the rapid spread of disease is equine flu in Australia. In North America, equine influenza (equine flu), a contagious viral respiratory disease, is relatively common and vaccination is used to help protect the horse population. However, in August 2007, a serious outbreak equine flu occurred in Australia, a country previously free of the disease, following the importation of an infected stallion. The virus rapidly spread into the horse population; over 70,000 horses were infected on approximately 9000 premises.Footnote 1 Conservative estimates of the costs incurred by the Australian Government to eradicate the disease were in excess of $342 million.Footnote 2 The movement restrictions imposed on horses resulted in the cancelation of hundreds of horse events, financial hardship and impacts to human health, including psychological distress.

Equine herpesvirus (EHV1) infection in horses can result in respiratory disease and fever, neonatal foal infections, abortions in mares and neurologic disease referred to as equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy. In April and May 2011, a large outbreak of equine herpesvirus in Utah at a national event resulted in approximately 90 confirmed cases of equine herpesvirus and equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy in 10 states.Footnote 3 Over 2000 horses were deemed exposed (either at the event or from a horse that attended the event) and 13 horses either died or were euthanized.Footnote 4 In Western Canada, 17 horses in 3 provinces were infected with the neurologic form of the disease.

In recent years, outbreaks of vesicular stomatitis virus, a contagious viral disease of equines, cattle, pigs and camels have occurred in the United States. Infected animals can develop blisters that swell and rupture, resulting in sloughing of the skin in their mouth, on their tongue and less frequently their muzzle, ears, teats and above their hooves. There is no vaccine and disease prevention relies on implementing effective biosecurity measures. In an outbreak that occurred in 2014 and 2015, 647 animals distributed over 435 premises in 4 US states were infected.Footnote 5 Another US outbreak in 2015 and 2016 affected 823 premises in 8 states.Footnote 6 Vesicular stomatitis is a federally reportable disease and outbreaks result in local and international movement restrictions and economic losses. Fortunately, Canada has remained free of vesicular stomatitis, the last outbreak occurring in 1949.

The significance of these disease outbreaks emphasizes the importance of developing and implementing biosecurity measures at the interface of all levels of horse contact and movement-from the biosecurity measures used in the daily care of your horse to those required when moving horses internationally.

Figure 3: Your horse - Part of a larger herd

Description for flowchart – Figure 3: Your horse - Part of a larger herd

The diagram consists of 5 circles that are different sizes and are layered around each other. Each circle represents a different aspect of the industry. Each circle contains text inside it. Beginning at the bottom with the smallest circle, the text inside the circles states: Individual Horse. The second circle states: Your Herd. The third circle states: Your Farm or Facility. The four circle states: Provincial and National Herds. The fifth and largest circle that contains all of the four other circles states: International Trade and Movement Agreements, International Herd.

This diagram illustrates the relationship of an individual horse to the national and international horse industry. It emphasizes the impact that disease left uncontrolled from an individual horse can have on the horse industry in Canada. Modified from Equine Biosecurity Principles and Best Practices: Disease Transmission; Government of Alberta.

2.3 Who is this document for?

Biosecurity is a shared responsibility that everyone in the horse industry must participate in. If you are responsible for a horse facility or the owner or custodian of horses, you share the responsibility to respect and implement appropriate biosecurity practices. As a horse owner or custodian, you are ultimately responsible for the health and welfare of your horse(s) and the level of disease risk you are willing to accept is a choice you must make. If biosecurity risks are unacceptable at a particular facility, you can either relocate horses (if boarding) or choose not to attend a particular event.

The guidance in the document is primarily for horse custodians, those individuals directly responsible for the care of horses or who have influence on those directly responsible.

One approach some horse owners and custodians take to minimize disease risks is to maintain a "closed herd" by eliminating the movement of horses onto and off of the property. While this may be feasible on some properties and can reduce disease risks, it does not eliminate disease risks posed by pathogens transmitted by biological and mechanical vectors such as mosquitoes, flies, ticks, feed, people, and tack or equipment.

2.4 What is the purpose of this guide?

The national biosecurity standard established a set of guidelines and recommendations to assist you in developing a biosecurity plan to minimize the risk of disease to your horse(s) or horse(s) you are responsible for. This user guide provides additional details and tools to achieve and implement the biosecurity elements in the standard. This will help keep disease out of your herd and neighbouring herds.

Be a good neighbour - Practice biosecurity to prevent the spread of disease.

2.5 Organization of the guide

The guide mirrors the organization of the standard and consists of seven biosecurity components that comprise a comprehensive on-farm or facility biosecurity program:

- Developing your biosecurity plan: Self-evaluation assessment checklist

- Monitoring and maintaining animal health and disease response

- New horses, returning horses, visiting horses, movements and transportation

- Access management

- Farm and facility management

- Biosecurity awareness, education and training

- Farm and facility location, design, layout and renovations to existing facilities

For each biosecurity component, a broad goal is established which is supported by a number of best practices to provide the overall direction for reducing disease transmission risks. If you own a single horse that rarely leaves an isolated property, you face different biosecurity challenges than horse owners or custodians and managers at a busy boarding facility or race track. Some components of biosecurity recommendations are divided into two groups: small farms and facilities and large facilities (which include, but are not limited to, event facilities and race tracks).

Section 3: Farm and facility specific biosecurity plan

Biosecurity: Keeping your horse(s) healthy and safe

3.1 Developing your farm or facility biosecurity plan

Developing a farm or facility biosecurity plan involves achieving the right balance between disease risk and prevention. While you and other horse owners and custodians may identify and implement similar biosecurity measures, each biosecurity plan is unique as it addresses the risks to your farm or facility.

It is helpful to have a basic understanding of the diseases that are most likely to pose a risk to your horse, (Refer to Annex 2) how these diseases are transmitted and methods of protecting your horse from disease. Work with your farm or facility veterinarian and industry experts on developing a plan.

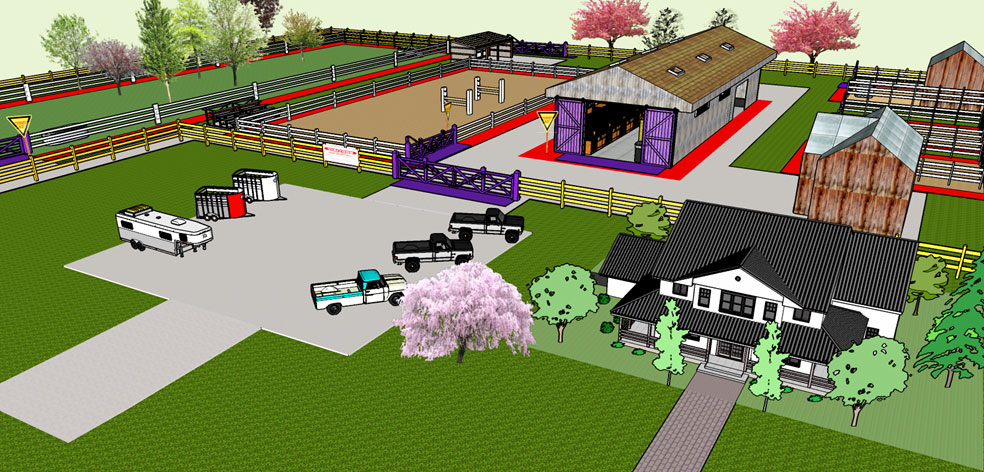

Step 1: Prepare a diagram of the farm or facility

A farm or facility diagram is useful for visualizing and identifying opportunities for horses to come into contact with other animals, people and equipment that are potential sources of disease.

Create a diagram of the premises and identify:

- property boundaries, fences and gates;

- location of neighbouring properties with horses or livestock;

- laneways, pathways, parking locations and traffic routes;

- pasture, animal housing, arena and eventing areas;

- storage locations for bedding, feed, manure and garbage;

- water sources, watering and feeding locations; and

- other areas on the site where people, horses and equipment may come into contact.

Review the diagram and create a list of the biosecurity concerns.

Step 2: Identify the risks - What diseases are concerns and how are they transmitted?

Diseases present in the local horse population and diseases that have previously occurred on the property are of primary importance. If you are travelling with your horse(s), consider disease risks from geographic areas you travel to. Talk to your neighbours that own horses, the clubs or associations you ride with, and your veterinarian to determine the status of local diseases.

Step 3: Review management practices and complete the self-assessment tool

Most horse care and management practices pose a risk for introducing and spreading disease. The biosecurity risks increase at a facility when there are additional people and horses with increased movement both on and off the farm or facility and around the property. Identify your daily care and management practices and any less frequent activities (for example, visits of non-resident horses to the property and resident horses returning after commingling with other horses) that might result in transmitting disease. Review your farm or facility diagram to help with this step.

Complete the biosecurity self-assessment tool using the information and biosecurity concerns identified in Steps 1 and 2 and the management practices identified above. (Refer to Annex 3 self-assessment tool). It is organized based on the seven components of a biosecurity plan.

When completed, review the self-assessment and identify areas where biosecurity practices are being effectively managed and those where improvements can be made.

Step 4: Identify biosecurity goals and best practices

From the review of the self-assessment tool and farm or facility diagram, identify the biosecurity challenges and risks. Using the biosecurity standard and user guide, identify biosecurity goals and best practices that can be implemented to address the biosecurity gaps. Discuss the strategies with your veterinarian and other sources of biosecurity expertise (provincial government livestock and extension specialists, industry associations, and universities) as necessary.

Step 5: Develop an implementation strategy

While all biosecurity risks need to be addressed, some will be more critical than others. Prioritize the biosecurity tasks and establish a timeline for their completion.

Establish short term goals and activities. These:

- can be planned and implemented within 12 months;

- are aligned to the current objectives and goals of your farm or facility; and

- often require minimal investment of time and capital.

Establish long-term activities. These can:

- be planned and implemented over more than one year;

- require changes in the physical infrastructure or layout of the farm or facility;

- require additional financial or personnel resources that are not currently available; and

- expand the overall goals and objectives of your management plan beyond their current scope.

Step 6: Review the effectiveness of the biosecurity plan and seek continuous improvement

The effectiveness of the biosecurity plan is measured by the adoption of its biosecurity practices, their integration into daily routines and the impact to the health status of horses on the property. When necessary, design and implement improvements to the biosecurity plan.

- assess the applicability and effectiveness of the biosecurity practices by reviewing key health performance indicators contained in the herd health records (see section 5.0) during and following implementation of the biosecurity plan and as changes to the plan are made;

- consult with your veterinarian and other advisors on biosecurity and adjust your plan as necessary;

- meet with family, staff, boarders and anyone with unrestricted access to the farm or facility at least twice yearly and following the implementation of a new practice to discuss the feasibility and effectiveness of each of the practices in your biosecurity plan; and

- review education and training sessions to identify areas for improvement.

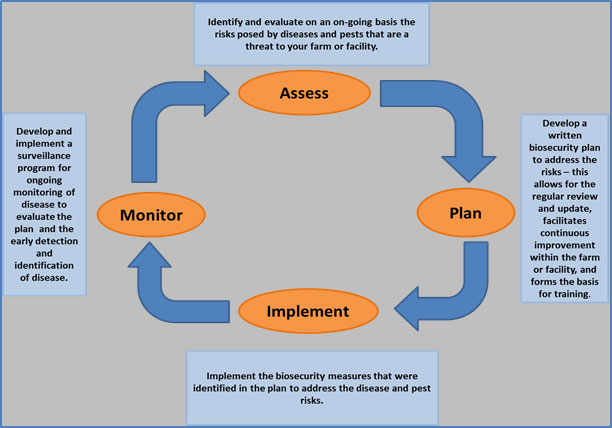

3.2 Cover your bases - Biosecurity: A cycle of activities

The implementation of biosecurity principles on a farm or facility can be viewed as a cycle of activities which includes:

- Assessing the biosecurity risks;

- Developing a plan that addresses the risks;

- Implementing biosecurity measures and procedures;

- Monitoring horse health, keeping records of sicknesses and treatments, and gathering disease and pest information to evaluate the plan and identify new risks; and

- Reassessing the risks and responses on an on-going basis to ensure continuous improvement.

Figure 4: Cycle of biosecurity activities

Description for flowchart – Figure 4: Cycle of biosecurity activities

Figure 4 is an illustration of the cycle of activities that should be completed to develop and implement a biosecurity plan. The cycle of biosecurity activities has four items in the centre with arrows pointing between them in clockwise direction. The first item at the top of the cycle is Assess. Moving clockwise, the second item is Plan, the third item is Implement and the fourth item is Monitor. There is a text box by each of these items in the cycle (four in total). Above the word Assess there is a box with the following text: Identify and evaluate on an on-going basis the risks posed by diseases and pests that are a threat to your farm or facility. To the right of the word Plan there is a box with the following text inside: Develop a written biosecurity plan to address the risks - this allows for the regular review and update, facilitates continuous improvement within the farm or facility and forms the basis for training. Below he word Implement is a text box with the following text inside: Implement the biosecurity measures that were identified in the plan to address the disease and pest risks. To the left of the word Monitor is a text box with the following text: Develop and implement a surveillance program for ongoing monitoring of disease to evaluate the plan and the early detection and identification of disease.

Assess: The risks posed by the introduction of pests and diseases that threaten horse health on your farm or facility are identified and evaluated in consideration of the seven components of a biosecurity plan. The identification and evaluation of risks will allow for current biosecurity issues within a farm or facility to be addressed.

Plan and Implement: A written on-farm or facility biosecurity plan is highly recommended, regardless of the size or type of facility. A written plan allows for regular review and update, facilitates continuous improvement within the operation, and forms the base for training.

Monitor and reassess: It is important that the design, effectiveness and implementation of a biosecurity plan be assessed not only on a routine basis, but also when changes in farm practices or biosecurity issues occur. Production practices should be reviewed frequently to ensure that implemented measures are effective in relation to pest and disease prevention and control.

Additional resources on developing a biosecurity plan

- Australia Horse Venue Biosecurity Workbook and Toolkit

- Equine Guelph

- Equine Biosecurity Policies and Best Practices book - Alberta Equestrian Federation (AEF) and the Alberta Veterinary Medical Association (ABVMA)

- Horse Biosecurity Guidebook - Saskatchewan Horse Federation and Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture

- Biosecurity Toolkit for Equine Events - California Department of Food and Agriculture

Section 4: Principles of infection prevention and control programs

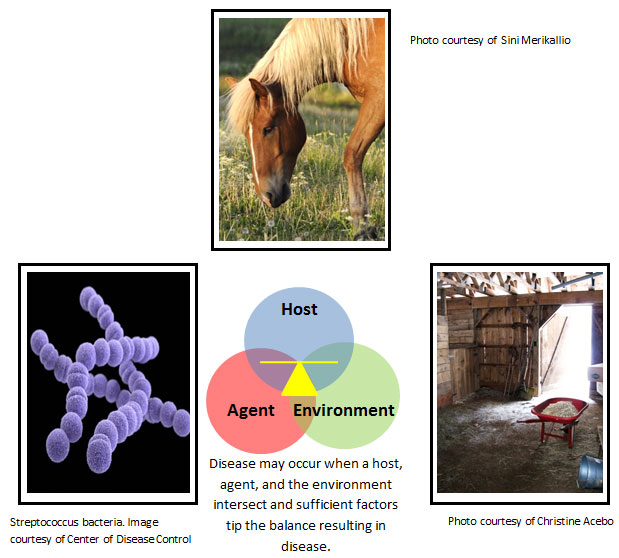

Infectious diseases in horses result from a complex interaction of three factors referred to as the disease triad:

- a horse that is susceptible to disease (the host);

- a pathogen such a bacterium, virus, fungus or parasite capable of causing disease (the agent);

- an opportunity for the host and agent to come into contact (the environment - which includes other horses and animals, the facility, food, water, soil, insects, equipment and humans).

Figure 5: The disease triad

Description for image – Figure 5: The disease triad

The diagram consists of a set of three overlapping circles of different colors. One circle contains the text host, one circle contains the text environment and one circle contains the text Agent. At the centre of the three intersecting circles is a yellow triangle with a yellow line on top representing a balance.

The disease triad illustrates that disease may result from the interaction of a susceptible horse (the host), a pathogen (the disease agent), and an environment favourable for disease development. There are many factors that influence whether disease will occur including the health of the animal, adequate nutrition, external stressors, the number of pathogens present and the ability of the pathogen to cause disease. However, there is a tipping point when sufficient factors overwhelm the ability of the animal to resist infection, tipping the balance in favor of the pathogen, which may allow disease to occur. Understanding the elements necessary for disease to occur provides the ability to influence and manage their impact to reduce disease. (Refer to Annex 2 and Annex 12 for information on equine diseases and parasites)

When discussing infection prevention, it is helpful to understand the distinction between infection and disease. Infection is the result of a pathogen invading and reproducing in a susceptible host. This does not always have an impact on the horse. Infection may lead to disease if there is a change from the normal function (for example damage to or a change in function of tissues and organs).

There are many host, agent and environmental variables that influence whether a horse will become diseased. Infection prevention and control programs rely on approaches that target these factors.

4.1 Sources of pathogens

- Horses that are infected but not showing signs of disease (a subclinical inapparent carrier or horse that has recovered from disease but still harbours the pathogen)

- Diseased horses

- Other domestic animals including pets

- Humans

- Food, water, and soil

- Equipment and other items (fomites)

- Housing areas and immediate surroundings

- Wildlife

- Pests (insects, spiders, ticks, rodents, birds and other animals that pose a nuisance to horses)

4.2 Methods of transmission

Pathogens can be transmitted (spread/transferred) by a number of routes; however, not all pathogens are transmitted by all routes. Pathogen characteristics, such as the ability to survive in the environment, can affect the mode of transmission.

- Direct transmission - Pathogens transmitted between animals through close physical contact.

- Direct contact - transmission through close physical contact between a susceptible animal and an infected animal, their bodily fluids or tissues. Depending on the pathogen, contact with skin, blood, saliva, respiratory fluids, urine, semen, fecal material and milk may result in transmission. In addition to the obvious modes of contact between individuals and groups, nose-to-nose contact over fences should always be considered.

- Indirect transmission - Some pathogens can be transmitted through an intermediate that has been contaminated and/or infected. This may be an inanimate object (a bridle, dirty clothing, contaminated feed and/or water) or a live animal (insect, rodent).

- Indirect contact - transmission through contact with people (for example, contaminated clothing, footwear, and/or hands), or with an inanimate object (fomite) through the shared use of equipment such as needles, syringes, artificial vaginas, dentistry equipment, contaminated vehicles, trailers, water buckets, and blankets. Pathogen transmission can occur over short distances (between animals on the same premises) and long distances (following travel to events and venues). Indirect contact with contaminated surfaces (dirty stalls and pens previously occupied by infected horses) can result in the transmission of pathogens. Pathogens transmitted by this route must be able to survive in the environment for the time required to come into contact with a susceptible horse.

- Ingestion - transmission by consuming feed and water contaminated by pathogens. The source of the contamination can include manure, urine, nasal discharge, and grass contaminated with parasite larvae.

- Aerosol transmission within a droplet - pathogens transmitted short distances by large fluid droplets generated by coughing, sneezing snorting and whinnying. Inhalation of these droplets can result in disease transmission.

- Airborne - transmission by very small particles that can be generated by disturbing contaminated materials. These can remain suspended in the air and travel over long distances.

- Vectors (living organisms) - transmission by a living organism (for example, people, animals, insects and ticks) infected with or contaminated by pathogens. In some instances, the insect vector is required for the development or multiplication of the pathogen prior to the pathogen being infective in the horse.

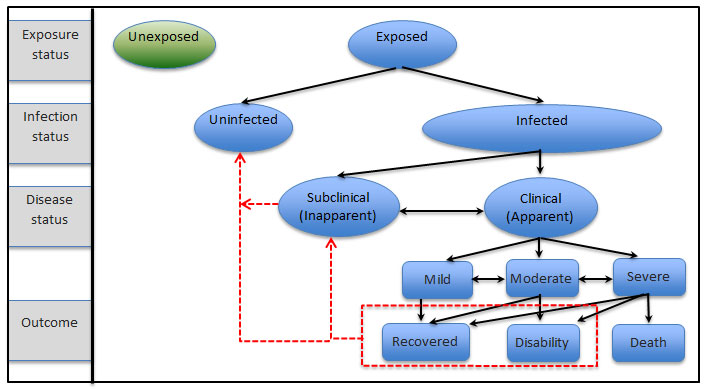

Figure 6: The status and spectrum of disease outcomes

Description for image – Figure 6: The status and spectrum of disease outcomes

The diagram provides a visual depiction of the outcomes of exposunnnnnre to disease and or status of disease in horses. There are four rows to the diagram. In the top row from left to right is a box with the text "exposure status", an oval with the text "unexposed" and an oval with the text "exposed". Two arrows point from the oval with the word "exposed" to ovals in the row below it. On the far left of the second row is a box with the text "infection status". To the right of this is an oval with the text "uninfected" and to the right of this an oval with the text "infected" . From the box reading infected are two arrows pointing to the third row. On the far left of the third row is a box with the text "disease status". To the right of this are two ovals. The first oval contains the text "subclinical (inapparent) and the second oval contains the text "Clinical (apparent). There is a two headed arrow between the two ovals. From the oval "clinical apparent" are arrows pointing to 3 boxes below it that contain the text "mild", "moderate" and "severe". There are two headed arrows between the boxes "mild" and "moderate" and between "moderate" and "severe". The last row starting on the left contains a box with the text "Outcome". To the right of this are 3 rectangles. The first rectangle contains the text "recovered", the second rectangle contains the text "disability" and the third rectangle contains the text "death". The rectangle "recovered" has arrows coming to it from the rectangles "mild", "moderate", and "severe". The rectangle "disability" has arrows coming to it from "moderate" and "severe" and the rectangle "death" has an arrow coming to it from the rectangle "severe". The rectangles with the text "recovered" and disability have a dashed box around them with dashed arrows pointing back up to the oval with the text "subclinical inapparent" and the oval with the text "uninfected" There is also a dashed arrow from the oval with the text "subclinical inapparent" to the oval with the text "uninfected".

Figure 6: illustrates the status and outcome of an individual horse or a group of horses following disease exposure. When an individual horse or group of horses are exposed to a pathogen, many factors (for example, genetics, age, health status, and the type of pathogen) influence the outcome of the exposure. Healthy horses with a robust immune system may not become infected following exposure, others may become sub-clinically infected, and some horses may develop clinical sickness and never fully recover. Horses that have been clinically infected (visible signs of sickness) may go on to become subclinically infected (no visible signs of sickness yet they still carry the pathogen) or clear the infection and become uninfected.

In a group of horses, the diagram represents the various stages and outcomes of exposure to a pathogen that can be encountered at any one period of time. There can be a gradient with some horses remaining uninfected while other horses are at different stages; some are only recently exposed, others are clinically sick and some already recovered. After exposure, some animals may continue to harbour the pathogen even if they have recovered from disease (for example, Streptococcus equi [strangles] or equine herpes virus-1 [rhino]).

When normal biosecurity measures fail, horses may become infected with pathogens that require treatment. Treatment should always be conducted under the consultation and supervision of a veterinarian. The veterinarian is the person best able to prescribe the right drug for the condition at the right dose for the proper duration of time to effect a proper treatment and response.

4.3 General concepts of infection prevention and control

A) Decrease exposure to pathogens: This is the most important approach; eliminating contact between animals and pathogens prevents infection and disease. If exposure occurs, horses may become sick if there are enough organisms (an infectious dose) that can bypass the horses' defence systems and then multiply to cause disease. Many of the biosecurity practices focus on reducing exposure including: separating healthy horses from horses that are sick or of unknown health status, not sharing horse equipment and tack, eliminating contact between individuals or groups over fences and stalls, and cleaning and disinfecting housing areas for horses on a routine schedule and before use by a different horse.

i)

- Separation of new arrivals - Separate new horses and horses returning to a herd (for example, following a period off the property and exposed to other horses) until their health status is determined and/or specific preventive measures are applied (for example, deworming and vaccination).

- Separation of potentially higher risk horses - Identify horses that are a higher risk for harbouring and transmitting pathogens and manage them appropriately (separate and treat) to minimize the risk. This may include horses that are: visibly sick (clinical infection), known to have been exposed to sick horses, and those that have recently recovered from a sickness. Horses that are clinically sick require separation from other horses and must be managed with additional biosecurity measures.

- Separation of susceptible horses - Separate horses that are more susceptible (young, pregnant, senior) to infection from other horses.

ii) Cleaning and disinfection (for example, barns, stalls, alleyways, and trailers) - Perform routine cleaning and disinfection to reduce the number of pathogens that are present. Ideally, all pathogens should be destroyed and removed by cleaning and disinfection; however, this can be very difficult to achieve. Therefore, the goal is to reduce the pathogen level below that which is required to cause infection.

iii) Hand hygiene - Perform hand washing, use hand sanitizers, and when necessary use clean disposable gloves (washing hands or using hand sanitizer after removal of gloves) to minimize pathogen spread.

iv) Personal protective equipment - Change clothing and use protective outerwear (boots, coveralls and gloves) to provide a barrier to the transmission of pathogens. Personal protective equipment can be used to protect the health of your horse and your own health.

v) Access control - Manage access to the property and horses to limit exposure. Minimizing contact, particularly contact with non-resident horses and their owners or custodians, reduces opportunity for disease transmission to resident animals.

vi) Traffic flow - Manage opportunities for direct and indirect contact between horses, people, equipment, vehicles trailers and other materials on the property. Fences, gates, pathways and signage can assist in keeping things where they need to be.

vii) Pest management - Minimize pests by: decreasing attractants (cleaning up spilled food and preventing pooling of water in paddocks and fields), controlling access and locations for pests to establish populations (using window and door screens in barns and removing unnecessary equipment and debris), and actively controlling pests through traps, bait and insecticides or pesticides when necessary. Insecticides and pesticides should be used with caution and according the manufacturer's recommendations as some products can be harmful to horses if over dosed, other animals, humans and the environment.

viii) Pasture management - Manage pastures to minimize the accumulation and transmission of pathogens and parasites among horses. (For additional details refer to section 8.3)

B) Decrease susceptibility to disease: The best way to decrease susceptibility is to ensure your horse has a high health status. This can be accomplished in the following ways: Providing proper nutrition, managing underlying disease, reducing stress, implementing a good parasite a control program, controlling housing conditions (for example, temperature and humidity), providing proper dental care, managing pain, and ensuring the proper use of antibiotics and other medications. There are other factors that affect a horse's susceptibility to disease that cannot be influenced to a significant degree: age, sex, genetics, and pregnancy. Develop and implement a horse health management program.

C) Increase resistance to disease: Vaccination is the primary method used to improve resistance to certain infectious diseases. Vaccines need to be given and stored according to the label directions in order to be effective. Many vaccines require two or more doses to be effective; booster vaccinations to maintain protection are often required on a yearly or more frequent basis. Unfortunately, a small number of horses may not be protected by a vaccine because they fail to generate a sufficient immune response, or the vaccine has been compromised through improper handling or administration. Additionally, a small percentage of horses may not be able to be vaccinated for health reasons. To protect these animals, it is important that the majority of horses are vaccinated to stop the spread of disease. Develop a vaccination program and vaccinate horses against diseases using a risk based approach in consultation with your veterinarian.

Titer testing - It is now possible to determine the level of antibody to several diseases by testing a blood sample from a horse. This may help determine when revaccination is necessary for some diseases.

However, while antibody titers can provide some indication of the level of immunity (protection) to a disease, it only provides one part of the picture. The level of antibody (the titer) required to provide protection is still unknown for many diseases. Additionally, other components of the immune system that are important in defending against disease, such as cell mediated immunity, are not measured.

Titer testing may be appropriate in some situations for certain diseases, however there are limitations which should be discussed with your veterinarian.

D) Treatment with medications to control an infectious disease: There are many different medications that can be used to help manage infectious disease, thus decreasing the chances of it spreading to other horses. The medications most commonly used to control bacterial infections are antibiotics. Due to the risk of infectious organisms developing resistance to the various antibiotics and potential adverse effects (for example, diarrhea), antibiotics (and other medications) should be used with discretion and only under the direction of a veterinarian.

Poor biosecurity and inappropriate or indiscriminate drug use can lead to antimicrobial resistance, which has a significant effect on human and animal health

Records management - Good recordkeeping and written protocols provide the ability to instruct staff on appropriate protocols and improves consistency in horse management. Written records provide the ability to evaluate, verify and make adjustments to the biosecurity program over time. Important records include: vaccination, parasite control (deworming), health records, arrivals/departures, contact groups (for example pasture or paddock turnout groups, cleaning and disinfection protocols, protocols for dealing with sick or potentially infectious horses.

Additional resources on diseases and disease transmission:

Section 5: Preventive horse health management program

Goal: There is a horse health management program implemented at the farm or facility that details daily care, disease prevention, and control practices. Every horse on the farm or facility is in compliance with the program to optimize disease prevention in a commingling environment.

Description: Preventive health management programs can improve the health and welfare of horses and increase participation at stables and events by reducing concerns over disease spread. It is important to realize that just as important as your own horses' health is the health of other horses.

5.1 Communication

Goal: The identification or suspicion of horse sickness is promptly communicated to maintain the health and welfare of other horses within a barn or facility where horses are kept. The staff and all the personnel are fully informed of the program and its importance.

Description: Disease notification procedures at farms with a few resident horses and where all owners know each other may be as simple as knowing each other's contact information. At event facilities with large numbers of transient horses that are owned and cared for by various people, communication strategies need to be well planned and documented. A simple, clearly written plan for communicating disease concerns provides a sound foundation for effective management.

Prompt communication of reliable information upon the suspicion or diagnosis of disease is important in:

- consulting with your veterinarian;

- ensuring horse owners, custodians and participants at the farm or facility understand the biosecurity measures being taken and what they need to implement;

- advising neighbouring horse farms and facilities of the disease risk; and

- minimizing anxiety, panic, and overreaction of horse owners and the public.

Figure 7: Example of a simple disease communication and response strategy

Description for flowchart – Figure 7: Example of a simple disease communication and response strategy

There are four arrows in a row each pointing right. There is text written inside and below each arrow. From left to right the text in and below the arrows state:

- Inside the arrow: "When - identification of disease". Below the arrow: "Horse appears to be sick. Establish health criteria that would indicate your horse may be sick - for example a list of clinical signs including changes in behaviour and activity level."

- Inside the arrow: "Who - owner contacts veterinarian". Below the arrow: "Horse owner consults with their veterinarian to determine the cause of sickness and potential treatment and management options."

- Inside the arrow: "What - communication". Below the arrow: "If the disease is easily spread and exposure of other horses is likely to occur, be a good neighbour and let other boarders and neighbours know that your horse is sick."

- Inside the arrow: "How and why - movement controls". Below the arrow: Separate your horse from other horses on the property to the degree possible. Implement movement controls for horses, people, equipment and materials as appropriate to reduce disease and spread."

In situations where multiple horses commingle and many custodians are involved, there needs to be a communication strategy with a designated spokesperson. Inaccurate or inappropriate information may negatively impact the credibility of the farm and facility and the greater horse industry.

It is important that custodians are able to react quickly to minimize the spread of disease to other horses. Owners and operators of farms and facilities where horses commingle (which include events, agricultural fairs, racetracks and auction marts) should have a communication strategy and disease response plan. Participants should be aware of the communication strategy and disease response plan in advance.

Best practices:

Develop a communication strategy tailored to the farm or facility that includes:

- developing a written and signed contractFootnote 7 between the custodian of the farm or facility and the horse owner or specified agentFootnote 8 that requires:

- aligning the preventive care of the horse with the farm or facility requirements;

- sharing all information regarding a health event that could affect other horses on the property;

- pre-arranging a process for disease disclosure to minimize disease spread;

- if your veterinarian is identified as being responsible for disease disclosure, you must provide your veterinarian with written permission to discuss the health concerns of your horse with the owner or operator of the facility;

- identifying an individual to be the point of contact for horse health information from owners and custodians;

- informing the designated individual promptly when a horse is suspected to be sick. If a different custodian provides for the daily care and observation of horse health, give him or her permission to communicate the health concerns;

- identifying a spokesperson in advance who is responsible for sharing information publicly. The spokesperson's knowledge and experience is important for ensuring that the information provided is accurate and presented clearly;

- developing and reviewing the information annually or if any significant changes occur; and

- identifying who is "doing what"; the roles and responsibilities:

- establish and define the biosecurity protocols for the disease situation, how are they different from the routine biosecurity measures and who and how is staff being informed. Ensure the current staff has been trained on the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for managing disease.

Considerations for boarding agreements/contracts and horse health

- A written boarding agreement or contract can improve communication between stable owners and boarders. By clearly outlining roles, responsibilities and expectations, an agreement can provide a predictable outcome when issues arise.

- Provide written permission on who can share information on disease.

- In addition to boarding costs, and services provided, ensure health requirements such as routine vaccinations, parasite control and preventive health care are identified.

- Confirm procedures for communicating medical and non-medical emergencies and providing medical attention for sick, injured or emergency medical situations to ensure the health and welfare of your horse and clarify the financial and legal obligations of both parties.

As provincial acts and regulations differ, research and consult professional advice on when developing boarding agreements/contracts.

5.2 Horse (herd) health management program

Goal: To achieve and maintain a consistent high level of health for all the horses within a farm or facility, develop, implement and maintain a horse health management program.

A preventive health program is only effective if you and other horse owners or custodians comply with the program to establish and maintain horse health. This also applies to horses that are temporarily at the farm or facility including: horses that are visiting, onsite for a short-term event, or only using the facility as a rest stop while in transit.

In facilities where horses are commingled and have been exposed to various environments (for example, shows, events, and other housing facilities) and potential diseases, it is important that the basic health status of the horse be determined and a consistent approach to health management be implemented to ensure the potential risk to resident horses and new arrivals is minimized.

Best practices:

- develop and document the farm or facility health management program in consultation with owners, custodians, veterinarians and other sources of biosecurity expertise (provincial government livestock and extension specialists, industry associations and universities)

- elements of a horse (herd) health program may include:

- premises identification and individual horse identification;

- vaccination requirements prior to entry and protocols post entry;

- disease testing requirements;

- parasite control program (deworming: type of product, timing, testingFootnote 9);

- observation and monitoring procedures for horse health;

- identification of sickness and response procedures; and

- hoof care (including: farrier area scheduling and cleaning; emergency contact info for farrier).

Horse owners and custodians must ensure the horses under their care and the properties they reside on or visit can be distinctly identified to allow appropriate horse health management.

5.3 Monitoring and maintaining animal health

Goal: To promptly identify disease, to minimize potential spread to other horses and to manage the well-being of the sick horse.

Early detection and treatment of sickness provides the best opportunity for a full recovery and reduces the likelihood of disease transmission.

Best practices:

- maintain up-to-date records of management practices (for example, vaccinations and horse arrivals, departures, and contact groups);

- routinely observe and monitor horse health. As a minimum, observation should occur on a daily basis. Increase the frequency of observation and monitoring when horses travel to and return from events, shows, tracks and other activities where commingling occurs (Refer to Annex 4 for information on conducting a horse health check, and Annex 5 and 6 for sample record sheets);

- observation and monitoring of horses includes, but is not limited to, identifying changes in:

- gait and movement;

- appetite;

- manure and urine production;

- mood or disposition and appearance; and

- temperature, pulse and respiration rate.

- establish criteria for identifying a sick horse which would then signal additional action. For example, an increase in temperature above the normal range of 37.0-38.5°C (98.6-101.3°F) should prompt a call to your veterinarian;

- know the normal range for horse vital signs. For an adult horse at rest:

- temperature: 37.0-38.5°C (98.6-101.3°F)Footnote 10;

- heart rate: 28-44 beats per minute;

- respiratory rate: 10-14 breaths per minute.

If there are health concerns, consult a veterinarian. The best practice to minimize suffering of the horse and protect other horses from potential disease, is to ensure there is the capacity for an immediate response.

5.4 Disease response and emergency preparedness protocols

Goal: To protect the health and welfare of horses, develop and implement a disease response and emergency preparedness protocols. All emergency preparedness protocols should include biosecurity considerations. In a disease response, the welfare of the sick horse(s) is protected and measures are implemented to minimize the potential disease risk to other horses. For non-disease emergencies such as flooding and fire, the health and welfare of all the horses are protected during evacuation, transport and housing in an alternative facility.