Biosecurity Planning Guide for Canadian Goat Producers

1 About the Planning Guide

This page is part of the Guidance Document Repository (GDR).

Looking for related documents?

Search for related documents in the Guidance Document Repository

1.1 Who should use this Guide?

This Planning Guide (the Guide) has been developed as an information resource for the National Farm-Level Biosecurity Standard for the Goat Industry (the Standard) to help goat producers prepare biosecurity plans for their farms. It is designed to serve the needs of goat producers across Canada, including all production types and herd sizes.

Producers are encouraged to prepare farm-specific plans, using both the Standard and the Guide. Individual farm plans will ensure that biosecurity measures suit the farm's size, layout and management practices.

Although on-farm biosecurity planning is primarily a producer's responsibility, family members, farm workers, advisors and others involved with the goat farm operation, often play an integral role in the implementation of the biosecurity plan and therefore can also benefit from using the Guide.

1.2 Why is biosecurity important for the goat industry?

Biosecurity is a set of practices used to minimize the transmission of disease-causing organisms in animal populations, including their introduction, spread within the population, and release.

Biosecurity is proactive and focuses on routine, day-to-day on-farm activities to protect the health of the herd by limiting the transmission of infectious agents that can cause disease in a goat or goat herd. Infectious agents are generally invisible, and can be moved from place to place in organic matter and on a wide range of materials that are frequently present in farming environments. Therefore, biosecurity focuses on reducing the risk of disease, on the assumption that infectious agents could be present.

For goat producers, biosecurity practices aim to achieve three general goals:

- Bio-exclusion: reducing the introduction of infectious agents to goats on the farm;

- Bio-management: reducing the spread of infectious agents among goats within a farm; and

- Bio-containment: reducing the spread of infectious agents between goat farms or from goat farms to other animal populations.

Biosecurity is important in reducing the risk and spread of endemic, economically-significant, production-limiting diseases, as well as avoiding catastrophic or foreign animal diseases. Reducing the risk of these diseases contributes to improved animal health, which creates the opportunity for day-to-day production improvement, cost savings and increased profitability, and protects the interests of both the producers and the industry as a whole.

Biosecurity practices can minimize the risk of exposure to zoonotic disease for producers, their families and their workers and reduce food safety risks potentially inherent in certain activities undertaken on the farm.

1.3 How to use this Guide

The Guide's best practices and resource information correspond with the organizational context of the Standard and focus on six key areas of concern:

- Sourcing and introducing animals

- Animal health

- Facility management and access controls

- Movement of people, vehicles and equipment

- Monitoring and records keeping

- Communications and training

The Guide is designed to assist producers in achieving the Target Outcomes identified in the Standard. The Standard also includes a set of self-assessment checklists that are the first step that producers should take when preparing or updating biosecurity plans for their farms.

The Guide provides a step-by-step planning approach and a detailed set of biosecurity best practices that will build on the self-assessments and help producers achieve the industry's Target Outcomes. They are intended to be adapted for use in each farm's biosecurity plans. In order to illustrate some of these best practices and important concepts, a number of case studies have been provided.

Biosecurity measures are closely related to both animal health and animal welfare practices; coordination of practices and measures among these important management disciplines is therefore recommended at the farm level.

It is important to note that the Guide, while comprehensive, is not a complete listing of all practices that could be used to meet the Target Outcomes. Other best practices may exist that support on-farm biosecurity.

A Glossary of Terms is provided in Section 3 of the Guide, and terms that are defined in the Glossary are bolded the first time they appear in the Guide.

1.4 Steps for developing a biosecurity plan

Here is a four-step process that will help you determine the risks within your goat operation, and select biosecurity practices to mitigate them.

Description for Figure 1

The figure illustrates four steps in the development of a biosecurity plan and the final process of implementing the biosecurity plan. The steps are as follows: 1. Identify diseases of concern; 2. Review your management practices; 3. Create a farm diagram and identify risk areas; and 4. Select biosecurity best practices for your plan. In three of the steps (1, 2 and 4), points of elevated risk specific to your operation should be identified.

Each of the steps is described in some detail in the following sections. Here is an overview:

First, identify the diseases that are of greatest concern to you and your herd. Some of these diseases will be of concern industry-wide, some regionally, and some will be specific to your operation. Not all diseases you identify will necessarily be present in your herd, but you may wish to establish practices to keep them out. Each disease is transmitted in specific ways — for example, by direct contact with the infectious agent or as an aerosol, through manure, water and feed, or by contact with tools, equipment or any facilities contaminated with infectious material. Additionally, while some infectious agents are very fragile in the environment, some survive for days, weeks, months and even years. The modes of transmission should be understood for each of your diseases of concern.

The next step is to review your management practices, and note where infectious agents could be transmitted during your day-to-day activities. It is important to identify these risk activities and/or locations so that control measures can be effectively implemented. They may include the movement and commingling of goats and other animals, actions of people on the farm, use of tools and equipment, and contact between animals and facilities.

During this process, you should also prepare a diagram of your farm and identify where control zones and identified risk areas should be established. The controlled access zone (CAZ) and the restricted access zone (RAZ)are areas of your goat operation where access by people, vehicles and animals is managed, and specific biosecurity practices are implemented. Identified risk areas are areas on the farm within the CAZ or RAZ, such as isolation areas, areas of known infection risk (e.g., abscess or caseous lymphadenitis), kidding pens, and nurseries, where heightened biosecurity practices should be used in order to manage their inherently higher risk of disease transmission.

Step 1: Identify diseases of concern and disease-specific risks

The following questions can help you determine which diseases should be identified as diseases of concern on your farm:

- How common is the disease in goats in your region?

- What are the effects of the disease on your goats' health and productivity?

- How difficult is the disease to control?

- Is the disease zoonotic and/or reportable?

- Is it either present on your farm or a disease you wish to exclude from your farm?

Your herd veterinarian and goat disease experts can help you with this process. Table 1: Diseases of Concern is provided as a resource and lists a selection of diseases that may affect goats. The list is not a comprehensive list of all goat diseases, but will help you develop your list of diseases of concern.

Table 1: Diseases of Concern

Table 1: Diseases of Concern lists some diseases that may affect goats. The table identifies diseases that have the potential to be zoonotic, any other species that may be susceptible to the diseases, and the sources of infection. The last column in the table provides space for you to indicate whether the disease may be excluded from your biosecurity considerations or should be managed. If the disease is managed, there is also an opportunity to rate the management effort as low, moderate or high. At the bottom of the table there are several rows on which you can record any additional diseases of concern for your farm.

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydophila abortus (formerly Chlamydia psittaci) |

Y | Sheep, llamas, alpacas | Bacteria are shed in birth products, which can contaminate pasture and bedding. Bucks, via sexual transmission, and carrier does, including those infected as kids, are also sources of infection. Invades through mucous membranes (mouth, eyes, genital) and causes abortion at next pregnancy. |

|

| Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) |

Y | All animals including sheep, cattle, cats, dogs | Bacteria are shed in birth products, vaginal fluids, feces and milk and can be spread as an aerosol either from kidding does or contaminated dried bedding and manure. | |

| Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii) | Y | Sheep | Oocysts are shed in the feces of cats (kittens) after eating infected mice. Cat feces contaminate feed (grain, forage) and pasture, which are then ingested by goats. Mice eat infected goat placenta and are a source of infection for the kittens. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthelmintic resistant (AR) gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) parasites | N | Sheep, llamas, alpacas | Failure to kill GIN parasites after deworming due to the parasites' resistance to that dewormer is an emerging problem. Inappropriate deworming practices can cause this resistance and goats are of particular risk because they a) fail to develop immunity to GIN parasites as adults and b) usually require a higher dose of dewormer to kill the parasites, so they are frequently inappropriately treated. New introductions pose a risk of bringing AR parasites onto a farm. |

|

| Coccidiosis (Eimeria spp) |

N | None | Oocysts are shed in the feces of infected kids and recovered adults and can build up in the environment (barn, drylot, pasture) until the load is high enough to cause disease in kids three weeks to six months of age. Fecal contamination of feed is associated with more severe levels of disease. | |

| Gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) parasites (Haemonchus, Teladorsagia, Trichostrongylus, Nematodirus) | N | Sheep, llamas, alpacas | Eggs are passed in feces of infected animals and contaminate grazing pastures. Introduced animals pose a risk of bringing in new infections. Adult goats can be affected as well. |

|

| Neonatal diarrhea (caused by coronavirus, rotavirus, enteropathogenic E. coli) | N | Lambs, calves, crias | Bacteria are shed in the manure of goats and can build up in the environment until the load in the kid rearing area is high enough to cause significant disease in kids less than two weeks of age. | |

| Neonatal diarrhea (caused by Cryptosporidia) | Y | Lambs, calves, crias | The oocysts of this protozoan parasite are shed in manure and contaminate the kidding and kid-rearing environment. If the load is sufficient, it can cause disease in kids two days to six weeks of age. | |

| Neonatal septicemia from opportunistic bacteria | N | Any very young animal | Kids that are born into a dirty environment and/or are colostrum deprived can contract bacteria from their environment. These bacteria enter through the navel or tonsils and invade the entire body. | |

| Orf / soremouth / contagious ecthyma (parapox virus) | Y | Sheep, llamas, alpacas | The virus lives in scabs, which drop off and contaminate the pens, feeders and hair. The virus can live for months to years in a dry environment. Some animals remain chronically infected and the virus can be isolated from scars of previous infections, and serve as sources of infection for other goats. | |

| Pneumonia (Mannheimia haemolytica, Mycoplasma ovipneumonia) | N | Sheep | These bacteria normally inhabit the throat of healthy goats. Environmental stressors (e.g., crowding, ammonia, temperature fluctuations, humidity, mixing of groups) will allow severe disease to occur. Occasionally respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) will cause acute, severe viral pneumonia in kids. The virus is shed in respiratory secretions from older recovered goats. |

|

| Pulpy kidney / enterotoxemia (Clostridium perfringenstype D) | N | Sheep | The bacterial spores are shed in feces and contaminate the ground and feed. If the animal lacks immunity and the feed source is rich (i.e. lush pasture, heavy grain), the ingested spores will grow in the gut, producing a toxin which rapidly kills the kid (sudden death). Adult does may also develop disease, but it is less acute. |

|

| Salmonellosis | Y | All animals | Feces from animals such as rodents, birds or other carrier animals contaminate feed. Diarrhea from infected animals contaminates the environment. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE) | N | Sheep | The virus is shed in respiratory secretions, which can be aerosolized, as well as in colostrum and milk. The virus infects goats of any age through the mucous membranes (respiratory tract, digestive tract, and conjunctiva). Sexual transmission and transmission in utero are also possible. Also causes hard udder, respiratory disease and arthritis. |

|

| Johne's disease | N | Sheep, cattle, deer, llamas, alpacas | Bacteria are shed in feces, colostrum and milk and are ingested by kids. The bacteria can survive for months to years in the environment. Transmission in utero from dam to kid also occurs. Shedding animals may not have symptoms of disease for several years. |

|

| crapie | N | Sheep | Reportable disease. Infected does will shed the prion in birth fluids and placenta at kidding. Prions contaminate the kidding grounds and infect other susceptible kids, adult goats and sheep, if present. Milk and urine are also sources of infection. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foot scald (Fusobacterium necrophorum) |

N | Sheep | The bacteria are ubiquitous in the environment. They can invade the soft tissues between the toes if the environment is dirty and wet, or if there is a wound or other foot trauma. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deer meningeal worm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) | N | Sheep, llamas, alpacas | This parasite, whose host is the deer and cycles through land snails and slugs, can infect goats if the goat inadvertently eats the infected snails and slugs. The parasite invades the central nervous system, causing disease. | |

| Listeriosis (Listeria monocytogenes) |

Y | Sheep, cattle | The bacteria are present in the soil and digestive tracts of many mammals, including rodents. Goats become infected after ingesting silage and other feeds that have been contaminated with feces. Growth of the bacteria is fostered by cool, wet conditions at normal to high pH. Also causes abortion and pink eye. |

|

| Rabies | Y | All warm-blooded mammals | Reportable disease. Contact with wildlife, most commonly foxes and skunks, is the main source of infection. Unvaccinated farm cats and dogs also pose a particular risk because of close contact with livestock and humans. | |

| Tetanus / lockjaw (Clostridium tetani) |

Y | All animals | The bacterial spores can live for decades in the soil. If the animal has a wound or kidding injury, it can become contaminated with the spore-containing soil. The bacteria then grow in the wound and produce a toxin which is absorbed by the nerves and causes disease. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biting and sucking lice | N | None | Nits (eggs) and lice are transmitted by direct contact between animals, contaminated tools, equipment and bedding. | |

| Caseous lymphadenitis (CLA) (Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis) | N / Y | Sheep, llamas, alpacas | The bacteria come from broken abscesses and from the lungs when abscess material is coughed up. They contaminate pasture and feed and can survive for days (water) to weeks (feed) to months (soil, feeders, grooming equipment). The bacteria then invade through skin and cuts in the mouth. CLA is an important cause of chronic wasting. |

|

| Dermatophilosis (D. congolensis) |

Y / N | All mammals | The bacterial spores commonly occur in the environment. Disease usually occurs when the animal is housed in dirty and wet conditions. | |

| Flystrike | N | All animals | The green-bottle fly (Lucilia sericata) is attracted to decaying organic material and will lay its eggs on live animals that are wet or dirty. Animals with diarrhea, wounds, and foot rot, are very susceptible to maggot infestation, which causes illness and death. Poor management of deadstock may attract more flies. | |

| Pink eye (Mycoplasma conjunctivae & Chlamydophila pecorum) |

N | Sheep, not cattle | Goats can be carriers of the bacteria and shed the bacteria in lacrimal secretions. Outbreaks occur when groups are mixed or new animals are introduced. | |

| Ringworm (fungal infection) |

Y | Sheep, cattle | The fungus prefers dark, moist conditions and can survive for a prolonged time in the environment. Transmission occurs easily through direct contact, as well as via grooming tools and equipment and shared pens at shows. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/ No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides | N | None | The bacteria can be spread through contaminated milking equipment and hands, and is highly contagious. Does may shed the bacteria in seemingly normal milk. Kids drinking infected milk will develop septicaemia and joint ill. | |

| Staphylococcus mastitis | Y | All animals | The bacteria are commonly present in skin infections (including people) and can be transmitted in many ways including milking, nursing kids, teat wounds, soremouth/orf lesions on the teats, dirty hands, poor udder preparation for milk, and lack of teat dipping. |

| Disease Category and Name |

Zoonotic (Yes=Y/No=N) |

Other Susceptible Species | Sources of Infection | Your need to exclude or manage (Low=L, Moderate=M, High=H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

There are a number of reportable diseases of goat, including some mentioned in this table (e.g., rabies and scrapie). For information on federally reportable diseases, visit the Canadian Food Inspection Agency's website. Some provinces also have a list of reportable diseases. Contact your respective provincial organization for more information (see section 1.5).

Identifying your diseases of concern will help you identify the risks on your farm. It is particularly important to know how they can be transmitted to your goats. As illustrated in Table 1, some diseases are transmitted directly from one animal to another, for example:

- direct contact (e.g., nose-to-nose contact, venereal transmission during breeding) or exchange of secretions or excretions (e.g., saliva);

- ingestion of infected milk or colostrum; or

- vertical transmission from dam to the fetus in utero.

Many diseases are also indirectly transmitted, for example:

- ingestion of feed, pasture, or water that has been contaminated with manure, urine, birth fluids or placenta. It is important to note that contamination may be from an infected or carrier animal, or from contact with pens, pathways, pastures, or vehicles that were previously contaminated;

- suckling from dirty teats contaminated with manure;

- ingestion of or contact with feed, water, pasture or bedding that has been contaminated by cats, dogs, rodents or other wildlife, which may be carrying an infectious agent; or

- contact with hands, boots, tools and equipment that are contaminated with infectious agents (e.g., contaminated hands during the milking process).

This information will help you identify the risks of disease transmission during your day-to-day and seasonal activities as you operate your farm.

Description for Figure 2

The conceptualized diagram illustrates that infectious agents may be transmitted in a number of ways. These transmission pathways include transmission from goats to boots to equipment, pastures, people, bedding and feed; from equipment to goats, pastures, people, bedding and feed; from people, bedding and feed to people and goats; and from rodents to equipment, bedding and feed.

Not all biosecurity practices are disease-specific. Many diseases are transmitted in similar and common ways; therefore, some proactive biosecurity practices will reduce the risk of transmission of multiple diseases.

Step 2: Review your management practices

You may have a set of management practices or standard operating procedures(SOPs) for your farm. If you do not have a set of SOPs, begin by preparing a simple outline of the activities that you and your farm workers carry out on a regular basis.

First, list the work activities you perform on a daily, and weekly basis, and those that you perform over a longer period, monthly, seasonally, and annually. Create a list of the steps that are carried out when completing each activity. Include a note about who performs each activity, what equipment is used, and where the activity usually takes place, including when the animals are moved from place to place.

Now think about the steps in each activity and make a note beside any that pose a risk for the spread of infectious agents, if present. Consideration should be given to areas or activities where goats and other animals, people, equipment, inputs (e.g., feed, bedding, sample collection containers), vehicles and/or your facilities have the potential to come in contact with an infectious agent. It is at the potential point of contact and/or point of introduction to your farm that biosecurity measures should be implemented to minimize the risk of disease introduction and spread.

Step 3: Create a farm diagram and identify risk areas

The concept of controlled access zones (CAZs) and restricted access zones (RAZs) has been accepted internationally and adopted by some livestock sectors in Canada. This approach is used to identify relatively large areas of a farm for biosecurity management and is the first line of defence on your farm.

Purpose of zoning

The purpose of zoning is to isolate the herd from infectious agents introduced by infected or contaminated animals, people, tools, equipment, vehicles, feed, water and pests entering the zone, and to contain any issues within the herd.

The controlled access zone (CAZ) outlines boundaries that encompass all of the active production areas of the farm, including the restricted access zone (RAZ) and the areas where service activities involving people, equipment and supplies are conducted. The CAZ boundary may be marked with signage and have a physical boundary. Certain biosecurity practices are in place for animals, people, equipment, inputs and vehicles prior to entry into the CAZ, which preferably occurs through a pre-established controlled access point (CAP).

The RAZ is a defined and identified zone within the CAZ and includes the areas where the herd is maintained. Therefore, the RAZ is intended to limit unnecessary entry, allowing access only under pre-defined biosecurity conditions. Specific biosecurity practices are in place for animals, people, tools, equipment and vehicles prior to entry into the RAZ. Access to the RAZ should be through a controlled access point.

Designating and managing additional identified risk areas within the CAZ and the RAZ will reduce the risk of the spread of disease between different animal groups within the herd or between an individual goat and the herd by minimizing exposure of animals of differing health status or susceptibility. Dedicated tools and equipment for use in each area or implementation of biosecurity protocols for cleaning and disinfection are important components in managing identified risk areas.

How zones work

- They are risk-defined: A risk assessment of the production activities is undertaken and their specific disease risks are determined. In order to effectively designate zones, appropriate biosecurity practices must be implemented in these areas so that specific risks can be managed.

- They are secure: They are often physically defined by walls, fences, secure doors and gates to ensure that animals and people cannot freely move into or out of a zone.

- They are visible: Biosecurity zones are clearly identified and people are notified of the zone-specific practices for entering, exiting and circulating with the zone.

- Access by people is managed: Access by and movement of people (i.e., farm workers, family members, service providers and visitors) are deliberately managed to support bio-exclusion, bio-management and bio-containment.

- Animal movement is managed: Farm workers are aware of the risks of disease transmission associated with animal movement into and throughout the premises. Movement is planned to mitigate these risks.

- Transition points are identified: There is a visually-defined entry point through which all traffic (vehicles, people, animals, inputs and equipment) will enter a CAZ and a RAZ, often referred to as a controlled access points (CAPs). Specific biosecurity protocols may be in place at access points; for example, tools and equipment may be limited to use in only that area or specific cleaning and disinfection may be required. Hands may be washed and protective clothing may be changed (e.g., coveralls) or cleaned (e.g., footwear).

- They are specific to each operation: The size and complexity of each operation and its existing facility layout will contribute to zoning decisions; i.e., a small, integrated meat herd that is essentially housed and handled together will employ a different zoning strategy than a larger dairy operation that operates as a closed herd, or an integrated breeding and meat operation.

Preparing a farm map and zones

The following diagrams are examples only and are not intended to be directly applied to your specific farm, production type and operational management. The examples do include some common or general farm layouts to assist you in determining the most appropriate designation of biosecurity zones and/or identified risk areas specific to your operation.

Sketch your farm layout

Using a pad and pencil (or working on a printed aerial photo, Google® or other map of your farm) prepare a simple map or diagram of your farm.

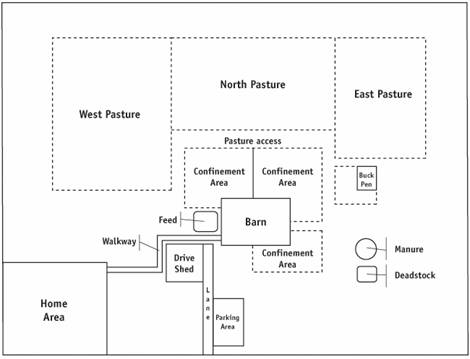

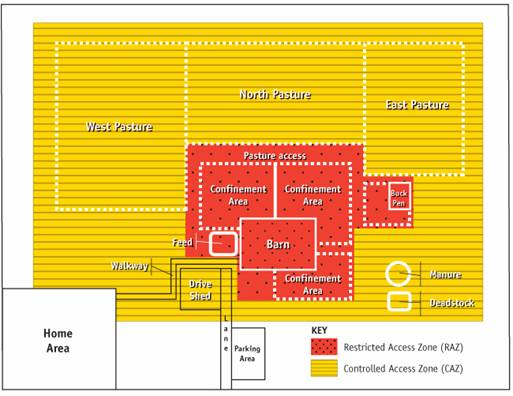

Description for Figure 3

The figure illustrates a conceptual example of a farm layout, including:

- Home area

- Farm buildings:

- Barns

- Drive shed

- Confinement areas

- Animal loading area

- Feed storage area

- Manure storage area

- Deadstock pickup area or compost location

- Barn office

- Driveways and lanes

- Parking areas

- Paths and walkways

- Pastures

- Pastures and housing areas for other animals on the farm

Select the restricted access zone (RAZ)

Identify the production areas in which goats should be protected from exposure to infectious agents from outside the farm and in which they should be protected from infectious agents within the farm. Also consider areas of potential traffic that are essential to the production area and the associated risks of disease transmission. There are various options, depending on farm layout and production practices.

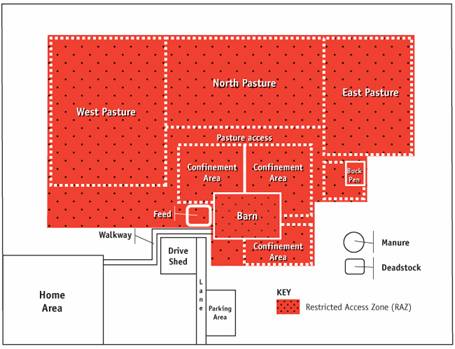

Description for Figure 4

This figures illustrates how on many farms, the restricted access zone (RAZ) includes all of the production areas and the pasture areas. This option creates a single zone for the full production facility and therefore reduces the number of times that goats, farm workers and others will move from zone to zone and carry out the required procedures. The RAZ includes the west, north and east pastures, the pasture access, the three confinement areas, the feed storage, the barn and the buck pen.

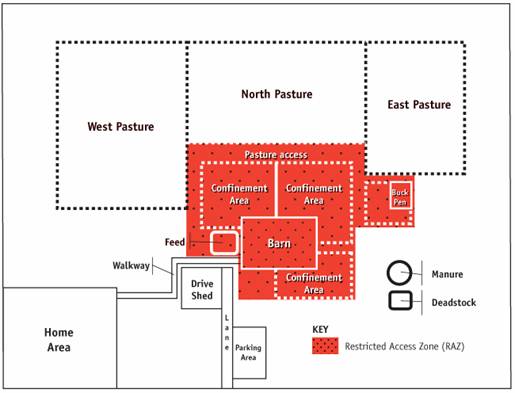

Description for Figure 5

This figure illustrates the option of having the RAZ include all of the working areas of the farm, but exclude pastures. This assists farms where defining a security zone that includes pastures is impractical. The RAZ includes the three confinement areas, the feed storage, the barn and the buck pen. This approach applies to farms with larger pastures and/or pasture areas that are not well-defined, or difficult to control. It allows a concentrated effort on biosecurity in the areas frequently used by the herd, farm workers and service providers and, therefore, the highest risk areas.

Select the controlled access zone (CAZ)

Once the RAZ has been determined, consider the areas that should be designated as the controlled access zone (CAZ). The CAZ contains operational facilities indirectly involved in animal production. It includes the areas in which service providers and farm workers would circulate before entering and after leaving the production area, and where they conduct their activities when they are not actively engaged with the goats (e.g., laneways, parking areas and equipment sheds). The CAZ encloses the RAZ.

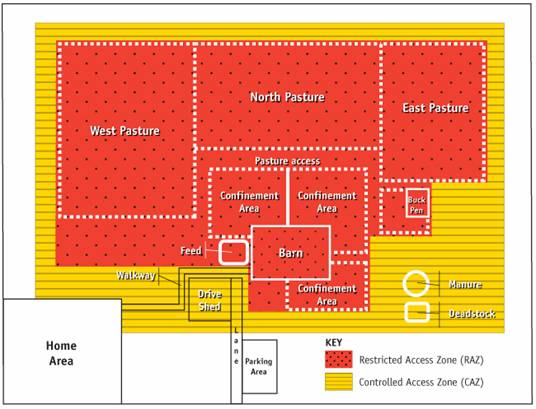

Description for Figure 6

In this image, the RAZ includes pasture, and the CAZ surrounds the RAZ and serves as a buffer for all of the areas where goats may be found. It also includes the barn office, walkway, drive shed, a portion of the laneway, and manure and deadstock storage. With this approach, there is a relatively small border around the entire farm that provides a transition to and from areas of the farm not directly used in goat production.

Description for Figure 7

In this image, the RAZ is designed to include only the more frequently-active goat production areas (e.g., barn, confinement area). The pastures and surrounding area (e.g., walkways) will be included only as part of the CAZ. This zone will be used to define the required practices and will also contain, as in Figure 6, the indirect production activities and enclose the RAZ. The controlled access zone (CAZ) includes the west, north and east pasture, the barn office, the walkway, drive shed, part of the laneway, and the manure and deadstock areas.

Identify controlled access points (CAPs)

When the zones have been applied to the farm's physical layout and its production practices, access points should then be identified. Controlled access points (CAPs) are a limited number of places at which people, animals, equipment, vehicles and inputs may enter and exit the zones. Some of these will be located where secure gates and doors, lanes and pathways already exist. Others will be defined by specific activities; for example, the movement of manure, the location of sick pens, and the delivery of feed.

An anteroom is recommended as the main access for people entering or leaving the RAZ. The anteroom is a transition area, which may also be the controlled access point, and facilitates the implementation of biosecurity protocols. In the anteroom, there should be a visual or physical marker which acts as the point for the implementation of biosecurity protocols. This may be a line painted on the floor, or a wall, wide bench or other type of barrier. For example, biosecurity protocols such as change of boots, outer clothing, hand washing, equipment cleaning and disinfection, should occur prior to crossing that point.

Controlled access points (CAPs) are usually physically identified, and specific practices should be followed whenever animals, people, equipment, inputs and vehicles move into or out of the zone. These are the critical points at which biosecurity practices can be implemented to minimize the risk of introducing and spreading infectious agents.

Determine identified risk areas

Copy the main production areas from your farm map/diagram onto another sheet in larger scale. It will be useful to keep them in similar relative positions and in somewhat similar proportion as in the farm map. Identify the activities that are undertaken in each of the areas on this diagram, both outside and inside the barn or the main production structure.

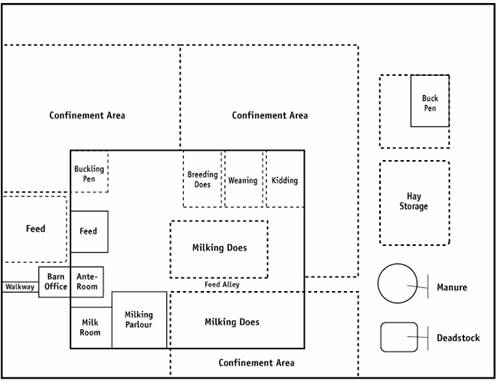

Description for Figure 8

The figure shows the main production area layout, which may include milking doe pens, buck pens, buckling pens, kid-rearing pens, weaning pens, breeding doe pens, kidding pens, isolation areas, hospital or sick area, breeding areas, handling areas, milking parlour and house, confinement areas, feed storage, manure storage and deadstock disposal.

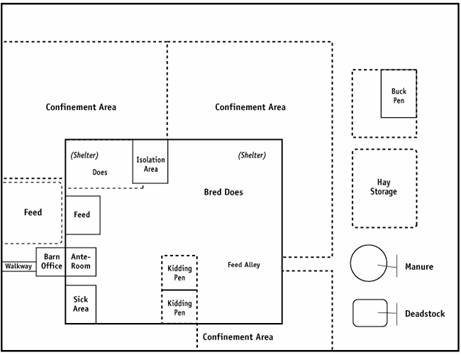

Description for Figure 9

This image shows the main production areas on a meat goat operation, which may include the buck pens, breeding doe pen, dry doe pen, kidding pens, isolation area, hospital or sick area, confinement areas, feed storage, manure storage and deadstock disposal.

Looking at these and other areas that are designated on your farm for specific activities, conduct a risk assessment of the areas. This may be as simple as classifying areas as low, moderate or high risk of disease transmission, based on:

- the health status and susceptibility of the goats that could be brought into the area;

- the nature of the activity;

- the goat's length of stay in the area;

- the likelihood of contact with other goats; and

- the anticipated traffic of farm workers, service providers and visitors.

It is also important to consider:

- areas where all visitors are allowed;

- areas where some or all visitors are restricted (i.e., should change clothing, wash and/or sanitize hands and footwear before being admitted); and

- areas where animals of differing health status are housed (e.g., new introductions, diseased animals or animals of unknown health status, sick animals undergoing treatment, animals on a health program).

Step 4: Select biosecurity practices for your plan

At this point in the preparation of your biosecurity plan, you have:

- determined your diseases of concern;

- reviewed your farm management activities; and

- designed your farm zones and identified risk areas.

It will be beneficial to also refer to the National Farm-Level Biosecurity Standard for the Goat Industry.

The Standard contains a self-assessment checklist for each key areas of concern highlighted in this Guide, as well as a worksheet to outline your biosecurity gaps and goals. These tools will help you focus your efforts on areas that require special attention on your farm.

Section 2 of the Guide provides a comprehensive collection of recommended best practices. These best practices are designed to reduce the risk of disease transmission:

- within your herd;

- within your facilities;

- in your day-to-day activities; and

- in the actions of workers, service providers and visitors on your farm.

After reviewing the biosecurity best practices, choose the practices that support the goals and address the gaps you have identified. Once you have worked through the sections of the Standard and the Guide that are relevant to your operation and put all of the required information together, you will have completed a biosecurity plan that is specific to your farm and will help you address your risks and promote a healthy goat herd.

1.5 Biosecurity resources

One the best sources of information for biosecurity and any other animal health-related topic is your herd veterinarian. Large animal veterinarians have extensive training and experience in the principles of biosecurity in livestock production that may be applied to goat production. To assist you in locating a veterinarian, the veterinary medical association for each province is provided below. Each association has a database of veterinarians and veterinary clinics for that province.

- College of Veterinarians of British Columbia

- Alberta Veterinary Medical Association

- Saskatchewan Veterinary Medical Association

- Manitoba Veterinary Medical Association

- College of Veterinarians of Ontario

- Ordre des médecins vétérinaires du Québec (French only)

- New Brunswick Veterinary Medical Association

- Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association

- Prince Edward Island Veterinary Medical Association

- Newfoundland and Labrador Veterinary Medical Association

For additional information on biosecurity, goat diseases and animal health regulations, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency of the Government of Canada is a valuable resource.

Many provincial governments have supplementary resources on goat herd management and biosecurity. There may also be provincial veterinary extension specialists available for your herd veterinarian to contact and gather additional information.

- British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture

- Alberta Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

- Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture

- Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives

- Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

- Ministère de l'Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l'Alimentation du Québec (French only)

- New Brunswick Department of Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries

- Nova Scotia Department of Agriculture

- Prince Edward Island Department of Agriculture and Forestry

- Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources

For current information on the goat industry in Canada, visit the Canadian National Goat Federation. There are also a number of provincial and sector-specific associations that may be applicable to your farm operation. The list below is not exhaustive, but highlights some of these associations.

- Canadian Goat Society

- Canadian Meat Goat Association

- Canadian Cashmere Producers Association

- British Columbia Goat Association

- Vancouver Island Goat Association

- Alberta Goat Breeders Association

- Manitoba Goat Association

- Saskatchewan Goat Breeders Association

- Ontario Goat

- Le Regroupement des Éleveurs de Chèvres de Boucherie du Québec (French only)

- Le Syndicat des Producteurs de Chèvres du Québec (French only)

- New Brunswick Goat Breeders Association

- Goat Association of Nova Scotia

Additional information on developing and implementing biosecurity plans may be found at the following sources:

- Date modified: