Biosecurity for Canadian Dairy Farms - Producer Planning Guide

Index 2. Control Area 2: Animal additions and movement

This page is part of the Guidance Document Repository (GDR).

Looking for related documents?

Search for related documents in the Guidance Document Repository

Cattle may be added to the herd to increase the size of the herd, meet quota requirements, replace cattle lost due to disease or injury, account for low reproductive performance or address an aging herd. Regardless of the reason, bringing new animals onto your farm poses one of the greatest risks of introducing infectious diseases. It is critical to consider biosecurity practices to mitigate these risks.

Keeping a closed herd is one way to protect cattle, and it is a best practice to keep the herd closed whenever possible.

Before adding any cattle to your herd, it is beneficial to determine the underlying reasons contributing to the need to acquire additional animals. Whenever possible, consider whether alternative solutions could eliminate the need for new animals.

However, when cattle must be added to the herd, it is important that you plan the introductions and utilize the best management practices outlined below.

Strategy 1: Limit purchases and number of sources

Acquiring cattle and introducing them into your herd is a major risk factor for introducing disease-causing organisms onto your farm. You can reduce this risk by limiting the number of cattle you acquire, the frequency of introduction and the number of sources.

Best Practice 1: Grow your herd from within.

Ideally: Operate a closed herd

In a "closed herd", the herd is repopulated only with animals bred on the farm under common biosecurity and health management conditions. Cows, bulls, calves or heifers are not brought to the farm for any reason, and they are not returned to the farm if they are removed for any reason.

Operating a closed herd requires production practices that eliminate the need for new production animals to be brought into the herd, while ensuring that quota can be met with the existing herd management program. The herd management program may include the purchase of semen and embryos, under suitable biosecurity conditions, that would provide for herd additions and allow genetic planning for the herd.

Information on planning and managing a closed herd can be acquired by contacting your provincial dairy association, or by talking to your veterinarian. Although operating a closed herd has many biosecurity benefits, the practice in itself cannot be the only disease prevention practice on the farm.

It is understood that, in many instances, operating a closed herd at all times is not realistic. If live cattle are to be introduced, the following best practices should be considered.

Best Practice 2: Establish a list of suitable suppliers if there is an acute need for expansion.

- Assess every supplier by asking the following questions:

- What is the current and past health status of their herd? Can this be supported by evidence such as disease records, treatment records, veterinary visits, and laboratory testing records?

- What biosecurity practices do they employ?

- Do they provide documentation with their cattle?

- Do they commingle animals from a variety of sources on the source farm or during transportation?

- How do they transport their cattle?

- How does the health status of the source herd compare with that of my own herd?

- Whenever possible, choose only known reputable suppliers with herds of equal to or higher health status than your own, and with disease monitoring and prevention programs.

- Maintain a relationship with the suppliers who have reliably sold you cattle in the past that were of low disease risk.

- Avoid purchasing animals from unknown sources or commingled sources, such as sales barns.

- Limit the number of sources.

Best Practice 3: Plan ahead for all additions.

- Review your records to determine your requirements for necessary additions in the coming months.

- Consolidate your inputs into a longer cycle, thereby reducing the number of times animals need to be brought in.

- Contact your supplier(s) in advance to ensure that your needs can be met.

Best Practice 4: Transport cattle in clean vehicles with no other animals.

- Purchase and transport directly from the farm of origin.

- If feasible, transport purchased cattle or show animals in farm-owned trucks or trailers.

- If using a commercial or shared vehicle, ensure that the vehicle is thoroughly cleaned and disinfected prior to use.

- Avoid commingling animals from other sources during transport.

- Ensure all vehicles are cleaned and disinfected after each use.

Strategy 2: Know health status of purchased animals

The key to safely acquiring new animals is not to purchase only disease-risk free cattle – this can be difficult to ascertain and is impractical in most cases. Rather, you need to conduct a risk assessment to determine the likelihood that an animal has or may be carrying a disease(s). Complete and reliable information of an animal's current health status, its disease history and the status and history of the herd of origin is invaluable for this risk assessment. This provides a basis for your decision-making regarding the purchase of the animal, and the risk mitigation steps needed if that animal does come onto your farm.

Best Practice 1: Conduct pre-purchase testing and examination.

- Where possible, test animals prior to purchase, as recommended by your herd veterinarian. Testing should be based both on your diseases of concern and the health history of the animal and farm of origin.

- Inspect each animal prior to purchase on the farm of origin to assess their health status.

- Look for hairy heel warts, foot rot and lameness.

- If possible, complete pre-purchase testing of all animals for:

- Bovine Viral Diarrhea (BVD) virus

- Bovine Leukosis Virus

- Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (Johne's disease)

- Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae or Mycoplasma bovis mastitis

- Use the guidelines from the Canadian Bovine Mastitis Research Network (CBMRN) for milk sampling.

- Have your herd veterinarian examine all new cattle immediately prior to introduction to your herd.

Best Practice 2: Ask for a vendor's declaration as to the origin of the animal(s), their health and vaccination status, and their treatment history.

- Gather information on an animal's current and past health status. Information of relevance includes:

- disease history

- vaccination status

- laboratory results

- treatments administered

- transportation history

- health status of the herd of origin, including disease history and vaccination program

- Assess the validity of the information. Ideally, there should be full disclosure and the documentation provided should be verified by their herd veterinarian.

- Ask for a vendor's declaration as to the property of origin and the health status and treatment history of the new stock.

- Ensure cattle identification can be cross-referenced to the property of origin for traceback purposes.

- Keep records of all new cattle introductions, including their health status, point of origin, identification numbers, point of purchase and method of transport.

Best Practice 3: Consult with your herd veterinarian before purchase.

- Review all information from the source herd with your herd veterinarian to assess the risk of purchasing each animal and introducing it to the herd.

- Request that your herd veterinarian be permitted to talk to the seller's veterinarian prior to purchasing cattle.

- Work with your veterinarian to determine an appropriate introduction strategy to address the potential risks. These recommendations could include testing, treatment, vaccination and isolation requirements.

- Complete a cost-benefit analysis relative to the price of the animal to decide whether or not to purchase the animal.

- Choose not to buy an animal that requires significant treatment and protracted isolation. This may be especially true when documentation is not available, or when you suspect it is not complete or accurate.

Best Practice 4: Know the health status of semen, embryos and breeding bulls prior to purchase.

- Inquire about biosecurity practices when choosing a commercial semen and embryo supplier. Specific details to discuss include:

- disease testing practices

- incidence of specific diseases

- response to disease cases

- participation in certification programs

- Request all supporting records and documentation.

- Purchase semen from known sources with certified production techniques.

- Keep semen tanks locked and allow only qualified people to handle semen.

- Consider the best practices in the first two sections – those related to purchase of cattle for all purposes – and also some elements related to semen – when purchasing breeding bulls.

- Use the information provided by the breeding bull vendor to determine if the bull presents excessive risk to your herd or if it would be a valuable addition to your herd. This information includes:

- lineage of the bull

- breeding soundness evaluations

- individual and herd health records

- additional test data regarding reproductive-related diseases

Strategy 3: Segregate, isolate and monitor

Once the decision has been made to introduce or re-introduce an animal(s) onto your farm, there should be a period of isolation and frequent monitoring. This will allow for early disease detection and response and ensure that there is a low risk of disease introduction into your herd.

Best Practice 1: Isolate incoming and returning cattle in a designated area.

- Designate an isolation area for incoming and returning cattle that is separate from other isolation areas (e.g. for sick animals or those under treatment).

- Determine the requirements for your isolation area based the mode(s) of transmission for your disease(s) of concern.

- Cattle should be prevented from nose-to-nose contact (a minimum distance of 3 metres is recommended).

- To prevent aerosol transmission, isolated cattle should not share the same airspace with resident cattle.

- Have dedicated isolation area feeders and waterers as well as equipment.

- Clean and disinfect the isolation area regularly and after each use. Promptly remove all manure and other wastes.

- Have farm workers who are handling these animals wash their hands, change their clothing and clean their footwear before working with other animals on the farm.

- Hold new cattle and returning resident cattle in isolation for 14 to 30 days or until surveillance and/or treatment/vaccination indicates a low disease risk.

- Timing needs to be sufficient in order to receive any test results, observe clinical signs of disease, and apply appropriate preventive health measures.

- Bacterial culture of milk and blood testing for specific diseases typically requires 14 to 30 days.

- The incubation period for many cattle diseases is two-three weeks or less.

- It is important to note the incubation period for some diseases is prolonged, and it is also possible for cattle to be asymptomatic carriers of certain diseases. In these instances, specific biosecurity measures to reduce the risk of disease introduction should be discussed with your herd veterinarian.

- If cattle are re-entering or coming from known sources of equal or higher health status, 14 days is usually adequate.

- If cattle are coming from an unknown source, have been commingled or imported from a foreign country, a minimum isolation time of 30 days is more appropriate.

- Timing needs to be sufficient in order to receive any test results, observe clinical signs of disease, and apply appropriate preventive health measures.

- If feasible, isolate animals from different source herds separately.

- If lactating cows are introduced, establish a plan for milking. Ensure that the cattle in isolation are milked last, and that all equipment is cleaned and disinfected prior to its next use with the home herd.

- Reduce the risk of reintroducing cattle when off-farm by incorporating biosecurity measures into your off-farm activities (e.g. shows, fairs). It is recommended to:

- inquire about any biosecurity requirements at the off-site location.

- limit contact between your cattle and cattle, manure, bedding and other products from other farms.

- require that anyone who needs to contact your cattle wash or sanitize their hands first.

- bring and use only your own feed, watering equipment, bedding and grooming or handling equipment.

- transport cattle in clean, farm-specific vehicles.

Best Practice 2: Observe and examine new purchases and returning cattle frequently for early disease detection.

- Observe and examine new additions frequently (at least twice daily).

- Create written protocols for monitoring. Consider monitoring:

- temperature

- attitude

- feed consumption

- clinical signs of disease (e.g. coughing, lameness)

- Record monitoring results and note any abnormalities in the animal's health record.

- Identify and train the staff who will monitor the animals.

- Have a plan to respond to any abnormalities.

Strategy 4: Test, vaccinate and/or treat

Ensuring that cattle new to your herd or re-entering your home herd are tested for diseases of concern, vaccinated and/or treated for any anticipated disease risk is a key step. The more complete your knowledge of the individual animal's health and disease history as well as the source herd's health and disease status, the more specific your testing and treatment can be.

Best Practice 1: Conduct post-purchase/returning animal testing.

- Follow a disease-testing program for new arrivals that is similar to the resident herd's program.

- Test herd additions as recommended during the isolation period and analyze the results before introducing them to the herd.

- Consult with your veterinarian about your disease-testing program, including interpretation of results.

- Collect and submit the appropriate samples as soon as the animals arrive in isolation, as it can take an extended period of time to receive test results depending on which tests are completed.

- If pregnant heifers are purchased, test both the dam and calves born subsequently to purchase for BVD virus to prevent the introduction of a persistently infected calf to the herd.

- Include embryo transfer recipients in your testing program.

Best Practice 2: Vaccinate to align with the resident herd's vaccination program.

- Consult with your veterinarian about your routine and purchased-animal vaccination programs.

- Initiate a vaccination (booster) series for new additions to match your herd's vaccination program.

- Vaccinate new additions while they are in isolation.

- Vaccinate your home herd, if required, according to your herd veterinarian's and the manufacturer's recommendations before introducing the new cattle into your herd.

Best Practice 3: Adequately treat or cull.

- Run purchased cattle through a medicated foot bath when they arrive at the home farm and repeat for 2-3 days after arrival.

- Complete a thorough diagnostic work-up for any new additions that become ill shortly after purchase. Rapid early detection can help prevent the initial case of a disease from spreading into the resident herd.

- Ensure appropriate treatment or cull, depending on the results of the diagnostic work‑up. Discuss the potential options with your herd veterinarian.

Strategy 5: Record location and movement

Animal identification is a fundamental component of livestock traceability. The Canadian Cattle Identification Program (CCIP) was established by cattle producers in 2001 and is mandatory for all dairy cattle leaving their herd of origin. Each head of cattle in Canada must have a Canadian Cattle Identification Agency (CCIA) approved ear tag. All tags are visually and electronically embedded with a unique identification number. The unique identification number is allocated by the CCIA for most provinces in its national database, except Quebec, where the identification program is managed by Agri-Traçabilité Québec (ATQ). The unique number of each individual animal is maintained throughout its life, to the point of export or carcass inspection.

The purpose of the program is to be able to identify animals and their origins during an animal health or food safety event and maintain export markets. The dairy industry in Canada has developed the National Livestock Identification for Dairy (NLID), which meets the requirements of the national identification program, with additional rules to better suit the industry.

Best Practice 1: Identify all cattle at birth with an approved national ear tag according to the NLID program.

- Tag all (registered and unregistered) cattle shortly after birth.

- Identify all cattle with an approved ear tag before leaving the farm of origin.

- Identify all imported cattle, other than those for immediate slaughter.

- Link identification to existing databases for milk recording, production, genetic evaluation and herd health records.

Best Practice 2: Work with your province to identify your premises.

- Identify all premises where cattle are housed, including secondary sites such as heifer barns and dry cow facilities.

- Register this information with your province.

Best Practice 3: Document all cattle movement and disposals.

- Keep records of all cattle purchases, cattle sales and removal of deadstock.

- Communicate all movement of cattle to the ATQ and CCIA.

- Maintain records for a minimum of 24 months after shipment.

Strategy 6: Manage movement within the production unit

It is crucial to consider the physical location of various groups of animals. Their proximity to others, their location relative to traffic barriers, and the air movement in the area, all impact the risk of disease transmission. Supporting information for these best practices has been provided in Section 2: Laying the Foundation of Your Biosecurity Plan.

Best Practice 1: Map the layout of your dairy facility, identifying the various production areas, and develop a flow chart of animal movement within the facility.

Preparing a list of these areas and pathways, and/or locating them on a sketch of the production area will be useful in illustrating where there are areas of greater or lesser risk for disease transmission, and therefore where biosecurity best management practices must carefully be considered.

- Refer to Section 2.2: Create a farm diagram to map the layout of your dairy facility.

- Identify all separate areas within the production area.

- Mark pathways that are used for the most common animal movements.

Best Practice 2: Using the map, divide the facilities, management activities and animal production areas into low, medium and high risk categories.

- Refer to Section 2.3: Designate Biosecurity Zones.

- Identify risk points that bring animals of lower disease susceptibility into contact or close proximity with animals of higher disease susceptibility or unknown disease status. These may include:

- housing arrangements or movement pathways within the production area

- pastures with fencing that does not limit nose-to-nose contact

- community pastures

- Review handling and processing practices to identify any that may increase the risk of spreading disease among production groups.

- Assign risk categories based on the likelihood of disease transmission.

Best Practice 3: Work with a veterinarian to establish the points of elevated risk and the order in which common/frequent movement of cattle should ideally occur within the production unit.

- Identify areas that require specific practices to reduce the risk of disease transmission. For example:

- access and handling limitations

- redirection of movement pathways

- more frequent or specialized cleaning and disinfection practices

- change of clothing and footwear

- hand washing

- Establish the order in which the common animal movement and animal handling should occur. This is based on susceptibility and disease status and generally follows the pattern of:

- younger to older

- healthy to diseased

- more susceptible to less susceptible

- Ensure that all movement pathways prevent direct contact with other groups of cattle, as well as indirect contact with their manure or excretions.

For more information on pathways and points of elevated risk, please see below.

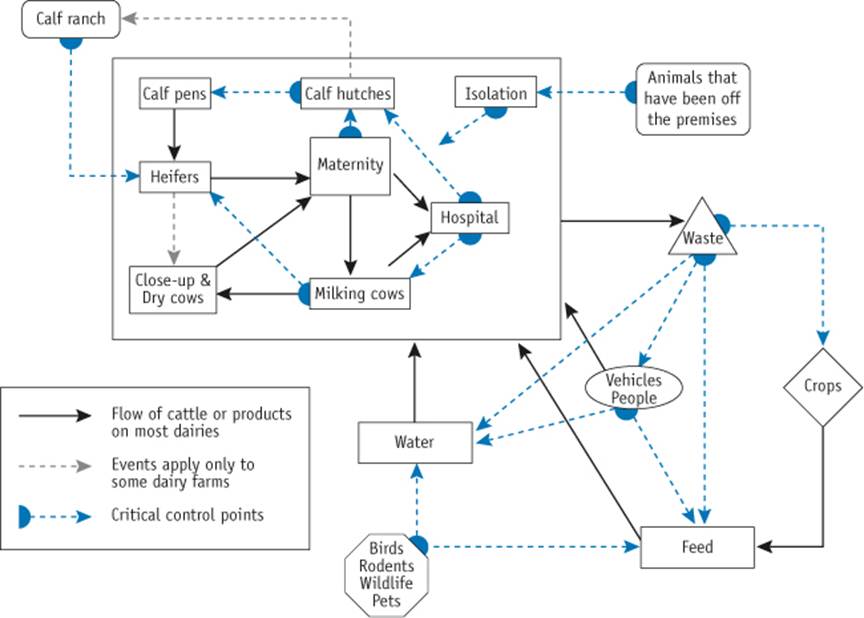

Description of the diagram of the risk areas, routes of travel and critical control points

This figure expands upon the concept of identifying the risk areas and routes of travel on a dairy operation. Specific points (areas or activities) where there is elevated risk of disease transmission are labelled as critical control points. Additional biosecurity measures are indicated in these areas or for these activities.

Within the dairy barn, the risk areas are the calf pens, calf hutches, heifer housing, close-up and dry cow pens, maternity pen, milking cow housing, hospital pen, and isolation area. Cattle and cattle products may flow between these areas. The critical control points are from milking cows to close-up and dry cows, from the hospital to the milking cows, from the maternity pen to the calf hutches to the calf pens and any flow from the isolation area.

Outside the dairy barn, there is the calf ranch, animals that have been off the premises, waste storage, vehicles and people, crops, feed, water, birds, rodents, wildlife and pets. Again, cattle and products flow between these areas, as well as into the barn. The critical control points are from the calf ranch to the heifer housing, from animals that have been off the premises to the isolation area, and any flow from waste storage, vehicles, people, birds, rodents, wildlife and pets.

This figure was developed by Aurora Villarroel, David A Dargatz, V Michael Lane, Brian J McCluskey, and Mo D Salman in their article Food for Thought for Food Animal Veterinarians: Suggested outline of critical control points for biosecurity and biocontainment on large dairy farms, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA), 2007; 230:808. It has been reproduced and translated by CFIA with permission from the authors and the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Best Practice 4: Include biosecurity concerns in expansion, remodelling or new construction activities.

- Consider biosecurity when you are renovating or undertaking new construction activities. Some relevant questions to ask include, but are not limited to:

- Does the layout and design support biosecurity (i.e. appropriate flow of animals and people through the facility, ability to adequately segregate different groups of cattle)?

- Will the materials and surfaces permit effective cleaning and disinfection?

- Will appropriate facilities be installed for biosecurity measures (i.e. hand washing stations, areas for cleaning and disinfecting equipment)?

- Can access be sufficiently controlled?

- Date modified: