Archived - Evaluation of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency's Enhanced Feed Ban Program

This page has been archived

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

February 8, 2013

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

- Table 1 - Financial resources received and spent for the CFIA's EFB and variance between planned budget and actuals ($'000s)

- Table 2 - Definitions of terms used to indicate the proportion of interviewees

- Table 3 - Overview of evaluation challenges, limitations and mitigation strategies

- Table 4 - Number of BSE cases confirmed in Canada, 2003-2011

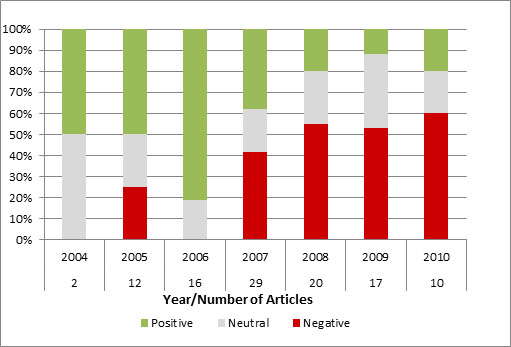

- Figure A - Changes in the attitude towards the EFB over time as reflected in articles related to the EFB published by select industry and market sources, by year and tone, 2004-2010

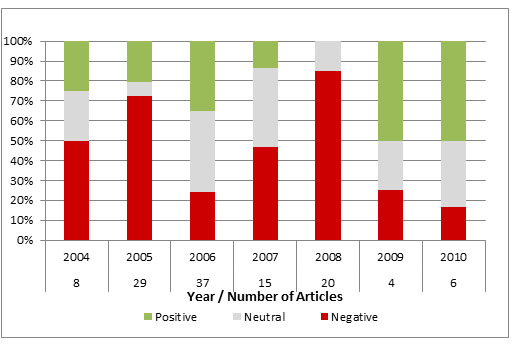

- Figure B - Changes in the attitude towards the EFB over time as reflected in articles related to the EFB published by general media source, by year and tone, 2004-2010

List of Abbreviations

- AAFC

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- AEB

- Audit and Evaluation Branch

- AMP

- Administrative Monetary Penalties

- APRI

- Alberta Prion Research Institute

- BSE

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy

- BVCRT

- Beef Value Chain Roundtable

- CFIA

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- CVS

- Compliance Verification System

- DPR

- Departmental Performance Reports

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- EFB

- Enhanced Feed Ban

- EOR/PMRS

- Enterprise Operational Reporting/Performance Management Reporting Solution

- FBTF

- Feed Ban Task Force

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- FTE

- Full-time Equivalent

- GATT

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

- MCAP

- Multi-Commodity Activities Program

- MRAP

- Management Response and Action Plan

- MRRS

- Management, Resources and Results Structure

- OFGD

- Other Federal Government Departments

- OIE

- World Organisation for Animal Health

- OPM

- Operations Planning Module

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture (formerly Program Activity Architecture)

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PWGSC

- Public Works and Government Services Canada

- QMS

- Quality Management System

- SRM

- Specified Risk Material

- TB

- Treasury Board

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat

- TSE

- Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy

- UK

- United Kingdom

- US

- United States

- USDA

- United States Department of Agriculture

- WHO

- World Health Organization

- WTO

- World Trade Organization

Executive Summary

Program Background

The Enhanced Feed Ban (EFB) is a part of the Government of Canada's Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) Program which is a horizontal initiative led by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). The main objective of the EFB is to accelerate Canada's progress in BSE management by preventing more than 99% of potential infectivity from entering the feed system as well as to enhance risk management of transmission of BSE in the cattle herd. To this end, the EFB aims to:

- Strengthen animal feed restrictions through amendments to the relevant regulations;

- Ensure compliance with control measures around prohibited materials and specified risk material (SRM) removalFootnote 1; and

- Increase the level of verification and confidence that SRM is segregated from feed, fertilizer and pet food and that prohibited materials are not fed to ruminants.

The removal of SRM from animal feed is an important animal health protection measure and an indirect public health protection measure. In the short-term, the most effective measure to protect public health from BSE is the removal of SRM from food and other consumer products, whereas over the long-term, accelerating the eradication of BSE from the animal population through the EFB will further ensure the protection of both animal and public health.Footnote 2 In addition, the EFB is also intended to help maintain consumer confidence and regain and expand market access for the regulated products by ensuring Canada's "controlled" BSE risk status from the OIE.Footnote 3

Multiple branches and programs within the CFIA are involved in the design, implementation and delivery of the EFB.

Evaluation Overview

In accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Policy on Evaluation, the primary objective of this evaluation was to assess the relevance (continued need, alignment with government priorities, and alignment with federal government roles and responsibilities) and performance (achievement of expected outcomes, as well as demonstration of efficiency and economy) of the EFB and provide recommendations to improve program effectiveness and efficiency, as necessary.

The evaluation team was composed of evaluators from an independent program evaluation firm, and the Audit and Evaluation Branch (AEB) of the CFIA. The evaluation approach and methodology were developed in consultation with the CFIA Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) and an independent scientific expert.

Note that documents and files served as the key sources for detailed information on the development and implementation phases, while interviews were often the primary source of data for evaluating the adequacy and effectiveness of EFB activities and procedures during the post-implementation phase. In addition, the available quantitative and performance data on EFB-specific activities and outcomes often had significant limitations and limited the ability to conclusively determine the effectiveness and efficiency of most of the EFB activities in the post implementation phase.

Findings – Relevance

Continued need for the Program

- The circumstances and factors that prompted the introduction of the EFB have not changed significantly and warrant continuation of the EFB.

- There are ongoing efforts led by the CFIA to identify potential modifications to the design and delivery of the EFB that would better address the needs of CFIA partners and stakeholders, including the industries regulated by the EFB.

Alignment with government priorities

- The EFB is aligned with federal government priorities, and the CFIA mandate.

Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities

- The EFB has two overarching objectives:

- safeguarding animal and public health; and

- facilitating market access for the regulated products.

While both objectives are recognized, there is a lack of consensus on the relative emphasis placed on animal and public health versus market access objectives of the EFB.

The federal government has a legitimate and necessary role in the EFB. Overall, the roles and responsibilities of the CFIA as well as those of the other partners and stakeholders are clearly defined and well understood internally and externally. However, there is a lack of awareness of the appropriate role for the CFIA vis-à-vis market access.

Findings – Performance

In this evaluation, it is important to note that achievement of the long-term outcomes (i.e. the effectiveness of the EFB) can only be assessed after 2015 due to the long incubation period of BSE.

Achievement of expected outcomes

- The process to develop the EFB regulatory framework was extensive and well-coordinated. The EFB regulatory framework was developed based on an adequate and appropriate level of consultation and risk assessment.

- The EFB implementation support activities were effective, particularly those relating to coordination and technical support.

- There is room for improvement in the current EFB management, decision-making and internal communication and coordination structures to better meet program objectives. In particular, there remains room for improvement in the system for results-based management specifically for reporting on performance, both internally and externally, to the CFIA.

- The CFIA has taken necessary and appropriate steps toward minimizing any negative impacts of internal and external factors on the performance of the EFB.

Demonstration of efficiency and economy

Management decisions affecting the re-allocation of staffing and resources and the effect of this re allocation on EFB planning and delivery across branches, divisions, and sections within the CFIA were not documented. This analysis also noted that certain EFB activities were not delivered as originally planned. The impacts (if any) of these changes on the achievement of the intended EFB objectives could not be determined. It is important to note that achievement of the long-term outcomes (i.e. the effectiveness of the EFB) can only be assessed after 2015 due to the long incubation period of BSE.

- The efficiency of the EFB relative to alternatives could not be assessed. Opportunities exist to address the challenges and limitations around financial tracking to better assess the efficiency of the EFB going forward.

- The CFIA had been successful in leveraging resources and avoiding duplication of activities in relation to the EFB.

Conclusions

The EFB is an important component of the Government of Canada's response to BSE, given the ongoing need to reduce the risk of transmission of BSE in the Canadian cattle herd to protect animal and public health and to facilitate market access for Canadian beef and other related products. Given its alignment with long-term federal government priorities and goals as well as current departmental responsibilities (including regulatory responsibilities), the EFB continues to remain relevant to the mandate of the CFIA.

The planning and implementation of the EFB both warranted and benefited from large-scale consultation and outreach, coordination and collaboration efforts and activities involving numerous stakeholders within Canada and some stakeholders outside Canada. The CFIA was successful and effective in bringing together and working with a large number of diverse stakeholders with a view to establishing consensus to develop and implement the necessary EFB regulatory framework and corresponding mechanisms and tools. To date, these immediate intended outcomes of the EFB have largely been met. However, it is too soon to assess the achievement of longer-term outcomes (i.e., the effectiveness of the EFB), due to the long incubation period, that is, the time from when an animal becomes infected until it first shows symptoms of the disease.

The EFB has faced some challenges since implementation. These challenges relate to the need for:

- strengthening the governance structure for the EFB; enhancing communication and coordination around the EFB internally and externally to ensure that the EFB adequately reflects the needs, priorities, and mandates of key EFB stakeholders and partners;

- facilitating the development of SRM testing and handling, disposal and use options and enabling technologies;

- improving performance measurement and management as well as financial tracking processes and systems; and

- addressing potential gaps in delivery of the EFB based on risk profiles and available resources.

Recommendations

Four recommendations have been formulated with a view to ensuring continuous improvement of the CFIA's EFB programming and achievement of the targeted outcomes.

The scope for this evaluation is 2004-2005 to June 2011. The BSE Program Management Committee was established in 2010 and was instructed to report to the BSE Fund Oversight Committee, which was created in June 2011. These two committees were renamed in 2012: the BSE Program Advisory Committee and the BSE Steering Committee, respectively. In September 2011, a new governance structure was put in place at the CFIA and the Animal Health Business Line Committee (AHBLC) was established. The BSE Steering Committee has been leading the BSE program oversight activities. This committee reports to the AHBLC and seeks recommendations from the BSE Program Advisory Committee for all of the BSE programming. The AHBLC makes activity prioritization recommendations to the Policy and Programs Management Committee (PPMC). An assessment of this new governance structure was not included in the scope of this evaluation.

Strengthen oversight, coordination and communication with regard to EFB-related activities, both internally and externally, by:

Recommendation 1

Strengthen the integration of the CFIA's EFB program objectives within the existing BSE committees as directed by the AHBLC or equivalent. As noted, the BSE Program Management Committee is tasked with ensuring that the CFIA's BSE-related activities for all program elements, including the feed ban, are discussed and developed internally in a coordinated, complementary and consistent manner. The BSE Fund Oversight Committee is tasked with ensuring that Agency activities pertaining to the distribution and use of BSE funds are in accordance with what was planned originally as well as developing a long-term strategic action plan to address reallocated funds.

Recommendation 2

Develop and communicate a plan for science-based policies related to SRM in support of the CFIA's EFB program objectives. As noted in Agency documents such as the "Discussion paper for drafting Canada's BSE Strategic Roadmap", the CFIA is committed to ensuring that any changes to its Enhanced BSE Programming (including the EFB) going forward are based on the latest scientific knowledge. Consequently, it is important for the CFIA to have access to the most current scientific knowledge with respect to BSE and SRM to ensure that policy and programming decisions reflect sound scientific evidence.

Mitigate the EFB challenges and gaps identified in this evaluation to ensure its effectiveness and efficiency by:

Recommendation 3

Improve performance measurement and management as well as budgeting and financial tracking procedures in relation to the EFB programming. There are related past and ongoing initiatives (e.g., upgrading information management systems within the CFIA, revising the performance measurement framework for BSE programming, and establishing the BSE Fund Oversight Committee) within the CFIA to strengthen tracking and reporting processes and systems for the Enhanced BSE Programming (and the EFB, as one of the components of BSE programming). Senior management commitment and oversight will ensure a sustained and coordinated approach in addressing both BSE and systemic issues that span across branches and programs.

Recommendation 4

Strengthen the planning for the allocation of EFB resources (human and financial) within the current governance process to address adjustments to the originally planned inspection scope and frequency. This would assess and address potential gaps in delivery of the EFB by ensuring that activities and establishments are being inspected at a level appropriate to their risk profiles and that adequate resources are available to each branch/program to support their respective EFB responsibilities.

The concerns over inconsistent application of the EFB between federal and provincial establishments/facilities as well as across federal establishments/facilities in different provinces could also be validated and addressed, if necessary. Ultimately, this exercise would place the CFIA in a position to better demonstrate the effectiveness of the EFB through sound and reliable EFB inspection and compliance verification activities despite the limitations of the SRM tests presently available to confirm the removal of SRM from the feed chain.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Program Overview

1.1.1 Context

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is a progressive, fatal disease that affects the nervous system of cattle. Commonly referred to as "mad cow disease," it belongs to a group of diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). Research is ongoing, but to date there is no treatment or vaccine to protect against BSE. It is commonly acknowledged that cattle become infected by consuming feed contaminated with meat and bone meal derived from infected animals. Feed restrictions are recognized internationally as a key method in containing the spread of BSE.

In 1997, acting on the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), Canada introduced through an amendment to the Health of Animals Regulations a pre-emptive feed ban to guard against the potential spread of BSE should it have been previously introduced. The 1997 feed ban prohibits proteins derived from most mammals from being fed to ruminant animals (such as cattle, sheep, goats, deer, elk, bison, etc.) At the time, this feed ban was considered to be an appropriate level of risk management for a country in which BSE had not been confirmed. The CFIA was responsible for delivering inspection and enforcement activities in relation to this feed ban.

Following the 2003 detection of a domestic case of BSE and subsequent detection of additional cases, the framework of the original feed ban was thoroughly reviewed. While surveillance results and the investigations of Canada's BSE cases detected since 2003 indicated that the 1997 feed ban was effective at limiting opportunities for the spread of BSE, enhancements to the ban were still deemed necessary. Consequently, a new regulatory framework was developed and the Enhanced Feed Ban (EFB) came into effect on July 12, 2007.

Of most significance, the enhanced 2007 feed ban regulations require the complete removal of specified risk material (SRM), which includes the skull, brain, trigeminal ganglia, eyes, tonsils, spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia of cattle 30 months or older, and the distal ileum (portion of the small intestine) of cattle of all ages, from animal feed, pet food and fertilizer. SRM has been excluded from the human food chain since 2003, and together with other ruminant tissues, were classified as prohibited material and banned from being fed to ruminants but not to other species. Under the EFB, SRM have been specifically banned from the entire terrestrial and aquatic animal feed chain, as well as fertilizer. Consequently, SRM are segregated at source and redirected to disposal or destruction. A permit system has been established to control the collection, transport, treatment and disposal of SRM. In addition, other enhancements have been made to the existing 1997 feed ban framework (e.g., to prevent feed cross-contamination at all points along the feed production and distribution chain from rendering facilities, to feed mills, to retailers and livestock producers). Altogether, amendments related to the EFB were made to regulations under the Feeds Act, the Health of Animals Act, the Fertilizers Act, and the Meat Inspection Act.

The EFB is a part of the Government of Canada's BSE Program, which is a horizontal initiative led by the CFIA. Under the BSE Program, the CFIA verifies that SRM is removed from the animal feed chain and the human food chain; monitors products entering and leaving Canada for adherence to Canadian standards or the standards of the importing country; monitors for the prevalence of BSE in the cattle population through surveillance; verifies that measures to control potential outbreaks are in place; and explains Canada's BSE control measures to domestic and international stakeholders (for example, through the veterinarians abroad program) to maintain confidence in Canada's BSE prevention and management efforts.Footnote 4

The other federal government partners in the horizontal BSE Program include the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), Health Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). Health Canada conducts research and risk assessments regarding human exposure to BSE and other TSEs whereas PHAC carries out public health surveillance and targeted research in this area. AAFC has been involved in supporting, stabilizing and repositioning Canada's beef and cattle industry, including through the provision of compensation payments to stakeholders impacted by BSE in Canada. The work of these four federal government organizations is interrelated in terms of protecting animal and human health, as well as in facilitating market access for Canadian agriculture, agri-food and agri-based products.Footnote 5 However, the entirety of the EFB specific funding ($26.6M per year, ongoing) is allocated to the CFIA for the delivery of EFB activities.

The following sections present an overview of CFIA's EFB objectives, activities, governance and resources. A more detailed program profile, as well as the program logic model, is provided in Appendix A.

1.1.2 EFB objective and outcomes

The main objective of the EFB is to accelerate Canada's progress in BSE management by preventing more than 99% of potential infectivity from entering the feed system as well as to enhance risk management of transmission of BSE in the cattle herd. To this end, the EFB aims toFootnote 6 Footnote 7:

- Strengthen animal feed restrictions through amendments to the relevant regulations;

- Ensure compliance with control measures around prohibited materials and SRM removal;Footnote 8 and

- Increase the level of verification and confidence that SRM is segregated from feed, fertilizer and pet food and that prohibited materials are not fed to ruminants.

1.1.3 EFB phases

For the purpose of this evaluation, the EFB activities were grouped into phases as follows:

- Development phase activities (2004-2007): consultations with regulated parties and other stakeholders (further details on EFB target groups and beneficiaries are provided in the Appendix A); risk assessments; and development of amendments to the relevant regulations;

- Implementation phase activities (2006-2007): included technical support and coordination, communication, and outreach activities prior to and after the EFB regulations came into effect on July 12, 2007; and

- Post-implementation phase activities (post-2007): ongoing activities such as inspections, verifying compliance and enforcing the new regulatory framework at federally regulated plants and feed, fertilizer and pet food establishments; issuing SRM permits and export certifications; and conducting research on SRM analytical and testing methods.

1.1.4 EFB delivery and governance

Multiple branches and programs within the CFIA are involved in the design, implementation and delivery of the EFB. Some branches and programs were involved intermittently or as necessary, such as the Public Affairs Branch and the Information Management and Information Technology Branch. Several branches and programs are involved in the EFB on an ongoing basis. They include:

- three branches: Operations, Policy and Programs, and Science

- four programs: Animal Health, Fertilizer, Feed, and Meat Hygiene

The Operations, Policy and Programs, and Science branches assume the lead role within the CFIA. Their primary responsibilities include (but are not limited to) the following:Footnote 9

The Operations Branch is involved in frontline inspection activities, including education and awareness and identification of compliance and non-compliance with regulations administered by CFIA. In this capacity, the Operations Branch has assumed a lead role with respect to enforcement activities.

The Policy and Programs Branch is responsible for policy and regulatory development; ongoing revision, interpretation, communication and management of policy issues; inspection program design; and development of training materials.

The Science Branch is responsible for conducting risk assessments, developing compliance validation technologies, and analyzing samples.

Branches and divisions implement and deliver the EFB, both individually and in collaboration. Each of the branches and divisions had roles and responsibilities relating to the delivery of the original 1997 feed ban (i.e., that pre-date the EFB). In this context, the EFB provided supplemental funding across branches and divisions to allow them to implement and deliver additional activities under the EFB.

In 2007, a Feed Ban Task Force (FBTF) was established to support the implementation of the EFB. The FBTF had specific roles and responsibilities vis-à-vis the EFB and was led by the Operations Branch. Following implementation, specific EFB activities and tasks gradually reverted to the relevant and appropriate branches and programs. The FBTF was disbanded at the end of 2007.

The current governance structures and consultation mechanisms (2011) related to various aspects of the EFB are described below.

The Animal Health Business Line Committee and the BSE Fund Oversight Committee within the CFIA: Under the new governance structure of the CFIA, launched in September 2011, business lines have been tasked with managing specific funds for which they are generally the majority recipient.Footnote 10 As a result, the Animal Health Business Line Committee has been tasked with having an oversight role for BSE funds for the CFIA. The mandate of this Committee is to ensure that CFIA activities pertaining to the distribution and use of BSE funds occur in accordance with Agency commitments and to develop a long-term strategic action plan to address reallocated BSE funds.

The BSE Program Management Committee within the CFIA: In 2010, in response to the 2008 summative evaluation of the Enhanced BSE Initiative, the CFIA established an inter-branch BSE Program Management Committee to improve communication and coordination of BSE-related activities to strengthen the linkage between the development and approval processes of individual activities (i.e., within branch business lines) and the horizontal, cross-branch priority-setting and policy development for the BSE program.Footnote 11 The overall objective of the Committee is to ensure that the CFIA's BSE-related activities for all program elements, including the feed ban, are discussed and developed in a coordinated, complementary and consistent manner.

The EFB Working Group: A joint government-industry EFB Working Group, co-chaired by the CFIA and AAFC, was established in 2007.Footnote 12 The goals of the Working Group are to review EFB-related measures being applied by packers and the rendering industry, their associated costs, and their contribution to the overall effectiveness of the EFB. Work is currently being done by the EFB Working Group in several areas to reduce the costs associated with SRM removal. Such work includes: assessing technologies available to remove specific components from slaughtered animals; making regulatory amendments to enable differences between the list of SRM to be removed from food and from animal feed; permitting wider use of composted SRM and SRM use in fertilizers; exploring options such as destruction technologies to generate less waste; and undertaking preparatory work for the 2012 CFIA review of the EFB.

1.1.5 EFB funding

The CFIA received $28.2 million over the first two years (2004-05 and 2005-06) for the EFB, followed by ongoing funding of $26.6 million per year since 2006-07. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the planned and actual allocation of EFB funding across relevant CFIA branches between 2005-06 and 2010-11.

During that time period, the CFIA spent almost $57 million less on the EFB than actually planned. While the CFIA noted that some of the budget variance could possibly be attributed to EFB-related activities carried out by other CFIA branches (e.g., Public Affairs Branch, Human Resources Branch, Legal Services Branch), this could not be confirmed via current financial tracking procedures. According to CFIA's Departmental Performance Report (2010-2011), the variance between planned spending and actual spending is related to funding being reallocated to expenditures that support this initiative, along with other Agency priorities.

| Section | 2005/6 | 2006/7 | 2007/8 | 2008/9 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 Table Note 6t | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned Budget Table Note 1t | 26,600 | 26,600 | 26,600 | 26,600 | 26,600 | 26,600 | 159,600 |

| PB: Operations | 17,900 | 17,900 | 17,500 | 17,500 | 17,500 | 17,500 | 105,800 |

| PB: Programs | 3,300 | 3,300 | 2,900 | 2,900 | 2,900 | 2,900 | 18,200 |

| PB: Science | 1,100 | 1,100 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 6,200 |

| PB: Other Table Note 2t | 4,300 | 4,300 | 5,200 | 5,200 | 5,200 | 5,200 | 29,400 |

| Actuals Table Note 3t | 14,100 | 17,600 | 20,000 | 18,600 | 16,100 | 16,800 | 103,200 |

| Act.: Operations | 10,400 | 12,500 | 13,600 | 12,500 | 12,000 | 10,900 | 71,900 |

| Act.: Programs | 400 | 800 | 1,400 | 1,100 | 700 | 1,400 | 5,800 |

| Act.: Science | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 400 | 300 | 2900 |

| Act.: Other Table Note 4t | 2,900 | 3,900 | 4,400 | 4,300 | 3,000 | 4,200 | 22,700 |

| Variance Table Note 5t | 12,600 | 9,000 | 6,800 | 8,000 | 10,600 | 9,900 | 56,900 |

Table Notes

- Table Note 1t

-

Includes: Employee Benefits Plan (20%), Corporate Overhead (COH), and Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) Accommodations.

- Table Note 2t

-

Includes COH, PWGSC Accommodations.

- Table Note 3t

-

Includes: Employee Benefits Plan (20%), Corporate Overhead (COH), and Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) Accommodations.

- Table Note 4t

-

(4-5) Includes COH, PWGSC Accommodations and portion of variance between BSE Fund and BSE I/O's.

- Table Note 5t

-

A portion of the variance amount was allocated to other corporate priorities. The variance between Planned Spending and Actual Spending is related to funding reallocated to expenditures that support this initiative, along with other Agency priorities. While efforts are made to meet the intended program objectives, reallocation occurs to deal with items which take precedence at the time (CFIA's 2010-11 DPR).

- Table Note 6t

-

Figures are draft until release of the final version of the CFIA's 2010-11 DPR.

Source: Compiled by CFIA Resource Management, June 2011, and CFIA's 2010-11 Departmental Performance Report (DPR)

1.2 Evaluation Objectives and Scope

1.2.1 Evaluation objectives

The evaluation of the EFB was identified as a priority in the CFIA's 2010-2011 to 2012-2013 Evaluation Plan. This evaluation meets a Treasury Board requirement to report on funding to enhance the 1997 feed ban in response to Canada's first case of BSE in a domestic animal found in 2003. As required by the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Policy on Evaluation (2009) and in accordance with the supporting directive and standard,Footnote 13 the primary objective of this evaluation was to assess the relevance (continued need, alignment with government priorities, and alignment with federal government roles and responsibilities) and performance (achievement of expected outcomes, as well as demonstration of efficiency and economy) of the EFB and provide recommendations to improve program effectiveness and efficiency, as necessary. The evaluation issues and questions related to relevance and performance are provided in Appendix B.

1.2.2 Evaluation scope

This is the first evaluation of the EFB and covers the program since its inception, from fiscal year 2004-05 to June 2011. The evaluation encompassed all EFB activities for which the CFIA received funding, including activities undertaken by the CFIA individually as well as in collaboration with EFB partners (federal and provincial government departments). It took into consideration the 2007 Evaluation of the CFIA's Feed Program, and the 2008-09 Summative Evaluation of the CFIA's Enhanced BSE Initiative as well as the Management Response and Action Plans (MRAP) and follow-up for these past evaluations.

As the EFB was implemented in July 2007, the assessment of the achievement of outcomes focused primarily on targeted short-term outcomes as outlined in the EFB logic model in Appendix A. Because of the long incubation period, that is, the time from when an animal becomes infected until it first shows symptoms of the disease, the evaluation of the long-term EFB outcome (i.e., the effectiveness of the EFB in controlling BSE) is possible only after 2015.

It is also important to note that:

- this evaluation is separate from the 2012 CFIA review of the EFB.

- the scope for this evaluation is 2004-2005 to June 2011. The BSE Program Management Committee was established in 2010 and was instructed to report to the BSE Fund Oversight Committee, which was created in June 2011. These two committees were renamed in 2012: the BSE Program Advisory Committee and the BSE Steering Committee, respectively. In September 2011, a new governance structure was put in place at the CFIA and the Animal Health Business Line Committee (AHBLC) was established. The BSE Steering Committee has been leading the BSE program oversight activities. This committee reports to the AHBLC and seeks recommendations from the BSE Program Advisory Committee for all of the BSE programming. The AHBLC makes activity prioritization recommendations to the Policy and Programs Management Committee (PPMC). An assessment of this new governance structure was not included in the scope of this evaluation.

The evaluation team was composed of evaluators from a consulting firm and the Audit and Evaluation Branch (AEB). The AEB oversaw the implementation of the evaluation and the consulting firm carried out the evaluation. The program data review, document and literature review and stakeholder interviews were undertaken from September to December 2011.

The evaluation approach and methodology were developed in consultation with the CFIA Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) and an independent scientific expert. The EAC was co-chaired by CFIA Executive Directors from the Evaluation Directorate and the Animal Health Directorate, and composed of representatives from CFIA branches (Policy and Programs, Operations, Science and AEB), as well as an external senior evaluation officer from a federal organization.

The evaluation was carried out in three phases.

- In the first phase, the evaluation team developed a detailed evaluation framework, including specific evaluation questions, indicators, and corresponding data sources and data collection methods.

- The second phase consisted of fieldwork to gather the necessary information and data.

- In the third phase, the evaluation team analyzed and integrated the collected information and data and then synthesized and reported the evaluation findings. EAC committee members provided input and feedback on preliminary findings and on the draft evaluation report. Any clarifications and revisions necessary in light of the comments received were made accordingly.

The evaluation methodology incorporated the collection and review of data and information from multiple primary and secondary sources as well as through multiple methods to facilitate triangulation and cross-examination of findings from multiple lines of evidence for each evaluation question. The following sections present an overview of the evaluation methods and their limitations. A more detailed description of the data collection and analysis methodology, as well as limitations and their implications on evaluation results, is provided in Appendix C and D.

1.3 Quantitative Method

1.3.1 Program data review

A list of the various EFB-related data initially provided by the CFIA was developed and used to guide systematic data review. Additional data was requested from relevant internal programs and branches following the development of the initial list, particularly performance measurement data. This review was used primarily to develop a financial profile of the EFB programming with a view to assessing program economy and efficiency as well as to verify and complement findings from other lines of evidence.

Reviewed data included funding and expenditure data; performance indicators and raw data; outputs and activities data from committees and working groups; and data extractions from resource/activity/compliance databases, progress and summary reports, annual reports, audits, submissions to external/international organizations, internal correspondence, etc. See Appendix D for more details regarding methodology.

1.4 Qualitative Methods

1.4.1 Document and literature review

A comprehensive review of EFB-related documentation and literature internal and external to the CFIA was conducted.

1.4.2 Program documentation and file review

The objective of the review was to develop a thorough understanding of the various aspects of the EFB, such as its context, history, rationale, design, implementation, delivery, and outcomes, as well as to verify and complement findings from other lines of evidence.

More than 500 documents, files and reports related to the EFB were reviewed as part of this process. The CFIA provided electronic or print copies of internal documents, files and reports; additional materials were publicly available and accessed online. Reviewed materials included strategic, regulatory and policy documents; funding and expenditure data; departmental planning and performance reports; audits; submissions to external and international organizations; terms of reference for committees and working groups; public communication and outreach materials; as well as past evaluations and their associated MRAPs.

Literature Review: In addition to the EFB documents, files and reports from the CFIA, materials related to the EFB produced by external sources (e.g., provincial governments, industry associations) were reviewed, when available. A sentiment analysis of articles related to the EFB that were published by selected industry or market and media sources between 2004 and 2010 was also conducted to track changes in the attitude towards the EFB over time. The tone of each article was assessed and coded as positive, neutral or negative. The resulting analysis was used as a proxy for industry perception of the EFB to track change in perception over time relative to media views, and thus complement the findings from interviews with industry representatives.

1.5 Stakeholders Interviews

A total of 60 interviews were conducted with internal (31) and external (29) EFB stakeholders to obtain views and input on various aspects of the EFB to inform the evaluation of program rationale and performance issues. A breakdown of the planned and actual number of interviews by interview category is provided in Appendix D.

Internal Stakeholder Interviews: Interviews were conducted with 31 internal stakeholders in person or by telephone. The CFIA compiled the original list of potential interviewees within relevant branches, programs and regions; this list was complemented by suggestions for additional and back-up interviewees from CFIA regional staff. The sampling maximized the inclusion of key CFIA staff involved in the design or implementation and delivery of the EFB and balanced representation of CFIA staff across relevant branches and programs, as well as between the head office and regions. The interviewees included senior CFIA management representatives involved in the design, implementation and delivery of the EFB; managers from Operations, Policy and Programs, and Science branches; and regional and field staff from across the country.

External Stakeholder Interviews: Telephone interviews were conducted with 29 external stakeholders. Potential interviewees were identified by the CFIA, by an independent scientific expert in the field of BSE, and by representatives of stakeholder organizations. The interviewees included provincial government staff; industry and association representatives from relevant industries (cattle and beef, feed, fertilizer and pet food); academic and scientific experts on BSE and SRM; and staff from the Center for Veterinary Medicine within the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

1.6 Analysis and Integration of Data

Following the fieldwork phase, the findings were analyzed and integrated across multiple lines of evidence. Information and data was validated within a method (i.e., corroborating the responses of multiple interviewees and multiple stakeholder groups) as well as between methods (i.e., corroborating interviewee responses with evidence from the document and literature review). The triangulation of findings across multiple lines of evidence was reinforced by having multiple evaluators engaged in the analysis and integration phase; these evaluators first independently and then collaboratively synthesized information and data from multiple sources and methods. Lastly, the preliminary evaluation findings were presented to AEB, the EAC and other relevant CFIA staff to identify factual errors and further confirm validity of results and conclusions. This feedback was addressed and taken into account in drafting this report.

Although the interviews were not designed or used to collect quantitative data, the interpretation of findings should take into account the extent to which certain perceptions or views were expressed or shared by interviewees. Table 2 defines terms (e.g., "some", "many") that are used in this report to quantify the proportion of interviewees or the proportion of groups of interviewees (e.g., internal stakeholders, industry or association representatives) who expressed similar experiences, views and opinions.

| Term | Proportion of interviews |

|---|---|

| "Majority" | Findings reflect the experiences, views and opinions of more than 75% of the interviewees |

| "Most" | Findings reflect the experiences, views and opinions of more than 50% but no more than 75% of the interviewees |

| "Many" | Findings reflect the experiences, views and opinions of more than 25% but no more than 50% of the interviewees |

| "Some" | Findings reflect the experiences, views and opinions of more than 10% but no more than 25% of the interviewees |

| "A few" | Findings reflect the experiences, views and opinions of less than 10% of the interviewees |

1.7 Challenges, Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

The evaluation challenges and limitations and the corresponding mitigation strategies are described in Table 3. The implications of these limitations are discussed in more detail in Appendix C.

| Challenge and limitation | Mitigation strategy |

|---|---|

| Due to a lack of clear separation of structure and activities between the EFB and (i) other components of the CFIA's BSE Program and (ii) the original 1997 feed ban, it was often challenging to attribute success or failure directly to the EFB versus other related components as well as to interpret certain information and data only in the context of the EFB. Interviewees also at times did not make a distinction between the EFB and other related programming when discussing the relevance and performance of the EFB. | Clarifications were made and sought during interviews to obtain interviewee opinion, feedback and input only on the EFB to the extent possible. In cases where this affected the interpretation of evidence in documents/files/data, clarifications were sought from CFIA program experts. In some instances, the impacts of this limitation on the evaluation findings were significant. |

| Challenges encountered in corroborating certain findings across multiple lines of evidence due to a lack of complementary information or data. While internal and external stakeholders generally recalled or provided relatively limited information on the development and implementation phases (2004-07), there were relatively few documents/files pertaining to the post-implementation phase (2008-10). Consequently, documents/files served as key sources for detailed information on the development and implementation phases, while interviews were often the primary source of data for evaluating the adequacy and effectiveness of EFB activities and procedures during the post-implementation phase. | Interviewees were provided with interview guides in advance so that they could review relevant information about past EFB phases and/or their involvement before the interview. Some interviewees also provided follow-up documents to complement the information they provided during interviews. The AEB also identified and shared up-to-date EFB documents/files to address specific findings/questions throughout the evaluation. Overall, this limitation was adequately addressed. |

| Since the CFIA provided the names of the internal stakeholders interviewed for this evaluation, this might have resulted in a possible selection/sampling bias. | The impacts of a potential selection/sampling bias were minimized by framing interview questions and prompts in a manner that encouraged interviewees to provide verifiable examples/supporting documents in relation to their answers, wherever applicable, as well as by triangulating multiple lines of evidence. Table Note 7t Nevertheless, some caution should be used in generalizing the findings attributed to internal stakeholders in this report across all relevant CFIA branches/programs/regions. |

| Identification of appropriate external stakeholders became a challenge during the fieldwork phase, as nearly half of the external stakeholders who were originally suggested as primary or back-up interviewees declined to participate. Additional external stakeholder names were obtained either from the CFIA and an independent scientific expert involved in the evaluation in advisory capacity or from the external stakeholders who declined to participate (i.e., within their organization). While the original target number for external stakeholder interviews was eventually reached, fewer international stakeholders and more industry representatives were interviewed than originally planned. The replacement representatives were deemed to be acceptable to the study, and were not deemed to have compromised the validity of the results. | Given the small sample size in relation to the overall population of external stakeholders—as well as the diversity of views/opinions within and among the numerous external stakeholder sub-groups—efforts were made to use complementary information, wherever possible (e.g., external stakeholder views reported in the media, reports on CFIA consultations with external stakeholders, etc.), to validate their views/opinions. This complemented efforts to identify appropriate interview candidates. Nevertheless, some caution should be used in interpreting and generalizing the findings attributed to external stakeholders in this report. |

For the purpose of this evaluation, available quantitative and performance data on EFB-specific activities and outcomes often had significant limitations:

|

Repeated efforts were made to identify and validate reliable quantitative data with CFIA representatives. However, in some instances, the impacts of this limitation on the evaluation findings were significant. Overall, the lack of valid, reliable and consistent quantitative data limited the ability to conclusively determine the effectiveness and efficiency of most of the EFB activities of the post-implementation phase The impact of this limitation on the evaluation findings relating to the achievement of expected outcomes are discussed in more detail in sections 3.2.3, 3.2.4, 3.2.5, 3.2.8 and 3.6.1. |

Table Notes

- Table Note 7t

-

Triangulation is a process through which answers to research questions generated by different data collection methods are compared. Where different methods produce similar findings, those findings are assumed to have greater validity; greater confidence in the results is therefore warranted. Conversely, findings generated by a single method are treated with caution.

2.0 Findings

2.1 Relevance: Continued Need for Program (R1)

2.1.1 Is there an ongoing need for the EFB and its components?

The circumstances and factors that prompted the introduction of the EFB have not changed significantly and warrant continuation of the EFB.

The continuation of the EFB is justified to a large extent by the fact that it is a requirement for Canada's BSE status, as determined by the OIE. Since 1998, the OIE has the mandate from the World Trade Organization (WTO) to officially recognize disease-free areas of countries for trade purposes.Footnote 14 The procedure for the official recognition of disease status by the OIE is voluntary and currently applies to four diseases, BSE being one of them.Footnote 15 Consequently, the OIE has developed standards to prevent the introduction of infectious agents pathogenic for animals and humans into an importing country during trade of animals and animal products, while avoiding unjustified sanitary barriers. The OIE also provides guidelines for countries to use in developing their respective import policies, based on a country's disease risk status. In the case of BSE, an effective feed ban is one of the conditions for maintaining Canada's controlled risk status as classified by the OIE, as well as for eventually qualifying for the negligible BSE risk status.Footnote 16

Support for some type of a feed ban (though not necessarily the EFB) was also noted in 2010, when the CFIA hosted a forum to clarify the range of BSE stakeholder perspectives and their implications for modifying the EFB, as well as to identify the important elements that must be a part of a revised strategy for the future of BSE control in Canada. The forum, with participation from government and industry representatives as well as other stakeholders (e.g., BSE researchers and experts), affirmed the continued need for the EFB going forward.Footnote 17

The view that the EFB should continue was also shared by the majority of internal and external stakeholders interviewed. The reasons cited for continuation of the EFB were twofold.

- Internal stakeholders and, to a lesser extent, external stakeholders noted that it was too early to assess the efficacy of the EFB in eliminating potential BSE infectivity in the Canadian cattle herd (as well as the associated animal and public health risks) due to the long incubation period of BSE, which ranges from 30 months to 8 years. Therefore, many stakeholders (especially internal) argued that the EFB should continue until enough time has passed to assess its effectiveness (i.e., after 2015).

- The other rationale centered on market access and was mentioned more frequently by external stakeholders. Some major export markets remain only partially open to Canadian beef products,Footnote 18 whereas international market access for Canadian feed and pet food products regulated by the EFB continues to be restricted, with a few exceptions.Footnote 19 As explained above, ongoing and future exports of these products are partially contingent on Canada continuing to meet OIE standards as a "controlled risk" country for BSE, which requires the demonstration of an effective feed ban.

To what extent does the EFB respond to the needs, priorities and mandates of its major stakeholders?

How could the design and delivery of the EFB be changed to better address and answer the needs of participating CFIA branches and divisions, other federal government departments and agencies, provincial government departments, and industries?

While support for the EFB is strong and widespread, there is no consensus on the appropriate or necessary level of feed ban enhancement to address the needs, priorities and mandates of key EFB stakeholders.

Stakeholder support for the continuation of the EFB was often contingent on further analysis of several interrelated issues and factors that, if addressed, would better meet their needs. The majority of stakeholders, both internal and external, highlighted a number of factors that should be taken into consideration in deciding whether changes and adjustments to the EFB are warranted going forward.

Some internal and external stakeholders noted that the level of effort required from both the CFIA and regulated parties to ensure the delivery of and compliance with the EFB across Canada was disproportionate relative to other diseases that pose a greater risk to animal (and human) health, but could be justified in light of the impacts of BSE on market access. While the challenge to align market access outcomes with the appropriate level of regulatory oversight extends to other CFIA regulations as well, it is particularly relevant in the case of the EFB since the impacts of BSE on market access can be significant. Therefore, these stakeholders indicated that there could be a need to develop a concomitant initiative on how to use the EFB more strategically and aggressively to differentiate Canadian products and gain competitive advantage in trade promotion and negotiation.

In addition some internal and external stakeholders reported the need for potential adjustments and revisions to the EFB in light of new knowledge about BSE and related technologies and systems since 2007 (e.g., atypical BSE strains, detection and testing techniques, surveillance methods).

It is important to note that the CFIA has been collecting input via stakeholder consultations on the need for and types of potential adjustments to the EFB in preparation for the 2012 review of the EFB. CFIA efforts in this regard include consultations with regulated parties carried out by the Enhanced Feed Ban Preliminary Implementation Review Working Group and the CFIA-AAFC Working Group focused on identifying options to reduce compliance costs.Footnote 20 While such consultations are geared towards developing a comprehensive and consensus-based path forward with respect to BSE management in Canada, they also involve discussions around the need for/type of a feed ban, which is one of the key enabling mechanisms for BSE management.

2.2 Relevance: Alignment with Government Priorities (R2)

2.2.1 Does the EFB continue to be consistent with government-wide priorities and the CFIA mandate?

The EFB is aligned with federal government priorities and the CFIA mandate. However, there is a lack of awareness of the market access component of the CFIA mandate, both internally and externally.

Interviews with internal and external stakeholders, as well as a review of the Speech from the Throne (2010) and related documents and websites, confirmed that the EFB is consistent with federal government priorities. More specifically, the EFB is consistent with:

- Ongoing federal government commitments to supporting the Canadian livestock industry, including beef producers, processors and renderers, to improve their profitability and competitiveness, as well as to support other related industries (e.g., fertilizer, pet food);Footnote 21

- The CFIA's goal to eventually obtain a negligible BSE risk status for Canada, as classified by the OIE;Footnote 22 and

- The CFIA's mission ("dedicated to safeguarding Canada's food, animals and plants, which enhances the health and well-being of Canada's people, environment and economy")Footnote 23 and its strategic objectives:

- A safe and sustainable plant and animal resource base;

- Public health risks associated with the food supply and transmission of animal disease to humans are minimized and managed;

- Contributes to consumer protection and market access based on the application of science and standards.Footnote 24

When discussing the alignment between the mandate of the CFIA and the objectives of the EFB, the majority of internal and external stakeholders referred to several aspects of the mandate of the CFIA, such as protecting Canadian livestock from diseases and pests, contributing to the safety of Canada's food supply, and safeguarding Canadians from preventable health risks.

However, market access was seldom mentioned or linked to the mandate of the CFIA by stakeholders. This could have been due to the stakeholders not being aware of the 2008-09 revisions to the CFIA's PAA (more specifically, the inclusion of "Domestic and International Market Access" as a CFIA "Program Activity"). The PAA was revised to highlight the significant CFIA programs and enable effective planning and reporting more strategically.Footnote 25 The efforts to raise the profile of market access within the CFIA's suite of activities reflect the increasingly important interrelationship between product safety and market access in a global economy.

Relevance: Alignment with Federal Government Roles and Responsibilities (R3)

2.2.2 Are the objectives of the EFB clear and relevant?

The EFB has two overarching objectives—safeguarding animal and human health, and facilitating market access for the regulated products. While both objectives are recognized, there is a lack of consensus on the relative emphasis placed on animal and public health versus market access objectives of the EFB.

The intent of the EFB is to accelerate Canada's progress toward eradicating BSE from the national herd; removing SRM as per the EFB eliminates more than 99% of the potential infectivity from the feed system.Footnote 26 The removal of SRM from animal feed is an important animal health protection measure and an indirect public health protection measure. In the short-term, the most effective measure to protect public health from BSE is the removal of SRM from food and other consumer products, whereas over the long-term, accelerating the eradication of BSE from the animal population through the EFB will further ensure the protection of both animal and public health.Footnote 27 In addition, the EFB is also intended to help maintain consumer confidence and regain and expand market access for the regulated products (by ensuring Canada's "controlled" BSE risk status from the OIE, see above).Footnote 28

Internal and external stakeholders did not raise any issues with respect to the clarity and relevance of the objectives of the EFB and affirmed the need for the removal of SRM from the feed system under the EFB. There was however, a lack of consensus on the primary objective or rationale behind the EFB. For many external stakeholders and some internal stakeholders, it was often their perception of the contribution of the EFB in sustaining and reopening export markets for Canadian products that was cited as justifying the considerable costs and efforts associated with the EFB rather than the contribution to achieving public and animal health. Although these two outcomes are closely interlinked, interviewees raised the fact that the comprehensive suite of EFB measures was implemented to address relatively small risks to public and animal health, especially compared to other diseases.

2.2.3 Is there a legitimate and necessary role for the federal government in the EFB?

The federal government has a legitimate and necessary role in the EFB. Overall, the roles and responsibilities of the CFIA as well as those of the other partners and stakeholders are clearly defined and well understood internally and externally. However, there is a lack of awareness of the appropriate role for the CFIA vis-à-vis market access.

The continued involvement of the federal government in the EFB through the CFIA was judged to be appropriate by the majority of internal and external stakeholders, given the Agency's past and ongoing responsibilities and activities. In particular, they highlighted the fact that the EFB built on a pre-existing feed ban overseen by the CFIA, as per federal regulations. In addition, the industries regulated through the EFB fall primarily under federal jurisdiction, with inspections delivered and overseen by the CFIA, as per their legislative authority relative to the Feeds Act and Regulations, the Health of Animals Act and Regulations, the Fertilizers Act and Regulations, and the Meat Inspection Act and Regulations. For example:

- Almost 95% of Canadian cattle are slaughtered in establishments and plants that are federally registered and inspected;Footnote 29

- Federal abattoirs generate an estimated 90% of the SRM waste in Canada (the remaining SRM waste mostly comes from provincial abattoirs);Footnote 30

- Feed mills are federally regulated businesses, and the federal government also regulates all fertilizers used in Canada;Footnote 31 and

- While the pet food industry is not regulated in Canada, the CFIA regulates pet food imports and provides verification and certification services for pet foods that are made in Canada and intended for export.Footnote 32

Are the roles and responsibilities of the CFIA and other federal and provincial departments involved in the EFB clear and well understood by internal and external stakeholders?

The majority of internal and external stakeholders generally reported that the roles and responsibilities of the different partners and stakeholders with respect to the EFB are clearly defined and well understood. Since implementation of the EFB in 2007, the roles and responsibilities of various CFIA partners and stakeholders (e.g., other federal government departments, provincial government bodies, industry associations and groups) with respect to the EFB have been further refined, clarified and reinforced through extensive discussions, as well as through the experience of working together, both formally and informally.

Some internal and external stakeholders indicated that another federal government organization, such as AAFC, would be more appropriate to address the market access objective of the EFB and envisioned the CFIA playing a supporting or complementary role in the area of market access. Greater clarity and communication on a number of issues would be beneficial in securing ongoing buy-in for the EFB from within the CFIA, as well as from the regulated parties. In particular, the following areas could be clarified:

- The extent to which safeguarding animal (and public) health remains the key driver of the EFB;

- The contribution of the EFB towards facilitating market access;

- The role of the CFIA in facilitating market access relative to other federal government organizations (e.g., as per the Memorandum of Understanding signed with the Market Access Secretariat of AAFC in 2010);Footnote 33

- The rationale for the importance and relevance of the EFB in those regions of Canada where market access is not a priority issue (i.e., regions that generally do not export EFB regulated products and where the prevalence of cattle slaughtering or concentration of EFB regulated products is low) to demonstrate why EFB efforts are nevertheless necessary in those regions.

There was a consensus that the CFIA was the most appropriate organization to oversee the overall implementation of the EFB regardless of the emphasis stakeholders placed on animal and public health versus market access. Many internal and external stakeholders noted that the CFIA was the only government organization that had the necessary regulatory authority, mechanisms and resources in place to ensure compliance with the EFB across Canada.

2.3 Performance: Achievement of Expected Outcomes (P1)

It is important to note that achievement of the long-term outcomes (i.e. the effectiveness of the EFB) can only be assessed after 2015 due to the long incubation period of BSE.

2.3.1 To what extent has the development of the EFB regulatory framework by the CFIA been effective?

The process to develop the EFB regulatory framework was extensive and well coordinated. The EFB regulatory framework was developed based on an adequate and appropriate level of consultation and risk assessment.

Design of the regulatory framework for the enhancement of animal feed restrictions (i.e., the Feeds Act, the Health of Animals Act, the Fertilizers Act, and the Meat Inspection Act): In December 2004, the CFIA announced amendments to relevant federal regulations regarding the prohibition of SRM from being used in all animal feed, including pet food and fertilizer. The proposed amendments were not finalized and published in the Canada Gazette until June 2006 to allow for adequate time to draft the amendments to incorporate the input and feedback from consultations and risk assessments.

Interviews with internal and external stakeholders as well as document review noted the significant contribution of consultations and risk assessments to the development of a sound and comprehensive regulatory framework, as described below. The finalized amendments did not come into effect until July 2007 to enable both the regulated parties and the CFIA to prepare for their implementation. The CFIA worked extensively with key stakeholders to determine which measures would best provide effective, rational and responsible feed ban controls. This included determining scientific merit, economic impacts, practical feasibility, and the consistency of approaches with other jurisdictions, including international trading partners, provinces and territories. The prolonged consultation period ensured that industry and other stakeholders, in cooperation with the CFIA, could identify and begin implementing the operational and infrastructural changes necessary to comply with the EFB.

The design of the EFB regulatory framework clearly took the consultations and risk assessments into account. The EFB regulations were drafted in a flexible manner so that relevant new knowledge and technologies related to BSE/SRM/prions could be reviewed or incorporated at a later stage.

Risk assessments and other studies to inform the regulatory framework: Thorough risk assessments based on the most up-to-date and complete information available about BSE and prions at the time were conducted by the CFIA to inform the development of the EFB regulatory framework. The CFIA evaluated different enhanced feed ban options using a risk reduction model to compare the time it would take to eradicate BSE from the cattle population.Footnote 34 The CFIA also conducted 12 qualitative risk assessments to inform proposed EFB regulations as indicated below.Footnote 35

- Risk reduction options (controlled incineration, cement kiln, alkaline hydrolysis);

- Containment options (on-farm burial, landfill and mass burial);

- Technologies under investigation (on-farm composting, mass composting, thermal hydrolysis, gasification only, and gasification with incineration); and

- Land application of sludge (treated wastewater from abattoirs and rendering plants).

These assessments focused on the risks associated with new cases of BSE arising in cattle and other domestic ruminants resulting from various on-farm and industrial disposal options of raw or rendered SRM or carcasses. They also provided an assessment of the risks arising from BSE via release and exposure pathways by spreading the residues on agricultural land or landfill, in connection with the domestic ruminant population. The establishment of infectivity reduction and the level of risk presented by those disposal options were also assessed.

2.3.2 To what extent have implementation support activities for the EFB regulatory framework by the CFIA been effective?

The implementation support activities have been effective, particularly those relating to coordination and technical support.

Most internal and external stakeholders indicated that extensive collaboration, coordination and communication within the CFIA and between the CFIA and relevant partners and stakeholders served as key success factors for effective implementation of the EFB. Some internal stakeholders noted that the breadth and depth of consultation, coordination, communication, and outreach efforts surpassed those for any previous CFIA initiative they had been involved with.

Feed Ban Task Force coordination and technical support activities: Interviews and documents showed that coordinated and targeted outreach efforts effectively built rapport between the CFIA and industry/other stakeholders.Footnote 36 The FBTF was heavily involved in these efforts and carried out 204 communication activities in 2007 (e.g., preparing briefing notes, making presentations, giving media interviews).Footnote 37 In addition, the FBTF issued numerous decision documents outlining policy clarifications to help the regulated parties to meet the intended health and safety outcomes of the enhanced feed ban more effectively.Footnote 38

The FBTF was disbanded and incorporated into a Strategic Projects Team in January 2008. The CFIA recognized the use of cross-sectional groups such as the FBTF as a best practice.Footnote 39 The formation of such groups was critical for effective and timely decision making by fostering a team approach to implementing a complex set of regulations that affected numerous stakeholders.

Other coordination, communication and outreach activities: In addition to the FBTF other key EFB groups and committees including the Enhanced Feed Ban Preliminary Implementation Review Working Group, the Feed Ban Steering Committee, the Industry Liaison Team, the Technical Implementation Committee, and the Inspection Oversight Evaluation Team. Many internal and external stakeholders indicated that these groups contributed to building consensus around complex policy and enforcement issues involving a diverse range of stakeholders while facilitating the provision of necessary implementation support internally and externally.

The Public Affairs Branch of the CFIA also drafted a broad communications plan targeting industry and industry associations, provinces, farmers, and the general public. The communications plan was further enhanced four months prior to implementation of the EFB to include an information package for all Members of Parliament, public notices in newspapers, and "Questions & Answers" on the CFIA website, among others. For the twelve months prior to July 2007, the CFIA initiated a comprehensive, national communications campaign to ensure that all regulated parties were fully aware of their responsibilities. Communication material was sent to the regulated parties across Canada, including industry associations, small abattoirs, feed retailers, pet food manufacturers, salvage operators, transporters, waste management corporations, zoos and auction markets. Booklets, brochures and posters were distributed to individuals, groups and organizations, and information was made available through a special page on the CFIA website. Public notices appeared in agricultural publications and community newspapers across Canada in April and July 2007, urging the regulated parties to contact the CFIA for information about the EFB regulations. A series of radio advertisements aired on rural community radio stations in the weeks leading up to the July 2007 implementation date.Footnote 40

2.3.3 To what extent was the implementation of the EFB regulatory framework by the CFIA well coordinated and effective in branches and regions across the Agency?

The implementation of some of the EFB components (e.g., training) was effective and generally well coordinated within the CFIA, whereas certain other components (e.g., development of laboratory analytical methods) could have been better coordinated and delivered more effectively.

EFB staff recruitment and training activities: CFIA representatives interviewed as part of the evaluation provided inconsistent views on whether CFIA recruitment efforts related to the EFB were adequate and effective. The 2005-06 Annual Performance Report for the EFB indicated that during the 2005-06 fiscal year, approximately 90% of the staffing for feed specialist inspection positions was completed for the EFB (i.e., approximately 115 staff hired), but limited information on EFB staffing numbers is available after this date or for other program areas (e.g., animal health).Footnote 41 Some CFIA representatives indicated that the number of staff hired was adequate, whereas others stated that insufficient funds were provided to individual branches and programs to attain the appropriate level of staff (see also Section 2.4).

CFIA and provincial government staff indicated that comprehensive training sessions and manuals organized and developed by the CFIA, as well as mentoring activities, adequately supported the work of staff, including new hires and provincial staff, involved in inspection and compliance verification activities. Both internal interviewees and the document review confirmed that the CFIA undertook training activities across Canada. These activities included a combination of conference calls and training sessions for at least 500 staff working in the areas of meat hygiene, animal health, feed and fertilizer as well as for SRM and EFB inspectors, supervisors and managers, and other relevant field staff.Footnote 42

Development of laboratory analytical methods to support a sampling verification system in compliance with the regulations: A few external and internal stakeholders indicated that the laboratory technologies and analytical methods used in Canada in relation to the EFB were on par with the best technologies and methods available worldwide at this point. However, current international SRM testing and analytical methods have significant limitations for use in the Canadian context. This is due to their inability to conclusively distinguish between prohibited proteins of any particular species and blood or milk proteins of the same species (the latter are exempt under the EFB).Footnote 43 It is worth noting that blood and milk proteins from all species (including ruminants) were excluded from the scope of the original 1997 feed ban. Based on the best available scientific evidence at that time, they were considered very low risk tissues for transmitting BSE. This position remained unchanged following the review of the original 1997 feed ban in response to findings of domestic BSE cases and, as a result, the exclusions were upheld in the scope of the EFB.

The document review confirmed a number of projects carried out by different CFIA labs to develop the necessary testing and analytical methods to aid verification of compliance with the EFB.Footnote 44 For example, the CFIA developed or adapted testing methods for the detection and identification of material derived from different animal species (bovine, sheep, goat, elk, deer, pig, horse, poultry and fish) in feeds to distinguish between prohibited (ruminant) and exempt species. However, up-to-date information was not available on the status of some of these projects, and more specifically whether any tests have been validated and transferred to a diagnostic laboratory for use to address the aforementioned limitations.

Due to the limitations of the presently available SRM testing and analytical methods, the CFIA relies primarily on inspection and compliance verification activities in support of the EFB. Inadequate use of testing or analytical methods to support EFB inspection and compliance verification activities had been highlighted as a potential area of concern by the CFIAFootnote 45 since the effectiveness of the EFB could not be fully demonstrated to internal and external stakeholders using scientific methods.

Inspections and enforcement activities, and import verifications, permits (tracking movement of SRM material) and export certifications: The CFIA developed a comprehensive and coordinated compliance and enforcement strategy so that the four relevant programs within the CFIA (feed, fertilizer, animal health, and meat hygiene) could assess compliance with EFB regulations and take enforcement actions if necessary in a consistent and unified manner.Footnote 46 Compliance with legislative requirements in a wide range of establishments and facilities was designed to include a range of inspection activities, such as monitoring, surveys, compliance verifications, audits of facilities and operations; sampling and laboratory analyses of regulated products; and reviewing of records and documents.

Enforcement is based on a graduated approach focussing on cooperation, education and compliance. Under this graduated approach, the CFIA can take one or more enforcement actions in response to non-compliance. Enforcement actions may include:

- Warning letters when an infraction is unlikely to have resulted in significant or serious harm, is obviously unintentional and is easily corrected, and where the company has made reasonable efforts to control the potential risk;

- Corrective action requests for situations in which the risk has been effectively controlled but which require the company to implement an action plan to prevent the reoccurrence of the event by an agreed date;

- Seizing and detaining products which may have been potentially cross contaminated;

- Recall orders for products that pose a human health, animal health or environmental risk;

- Prosecutions; and

- suspending or cancelling permits for serious or ongoing unresolved issues.

However, some internal stakeholders noted that in some instances, existing enforcement provisions were not strong enough or the original enforcement protocols were not implemented as planned. In particular, the fact that the use of administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) had not been implemented under the Feeds Act, the Fertilizers Act, the Meat Inspection Act to address certain cases of non-compliance, despite this measure being explicitly identified in original compliance and enforcement plans for the EFB.Footnote 47

Documents and interviews confirmed that compliance inspections now occur at various types of facilities including inedible rendering plants, commercial feed manufacturers, fertilizer/fertilizer supplement manufacturers and composting facilities, feed and fertilizer retail outlets, on-farm feed manufacturers, and ruminant feeders.Footnote 48 With regard to expanded inspection activities for feed and fertilizer products, the document review also confirmed that inspections now include verification of feed and fertilizer invoices and documentation, compliance with permit conditions, and presence or absence of prohibited materials, as appropriate.